Why do food allergies, including peanuts, so plague the U.S.?

A 2013 study published in JAMA revealed that people in the U.S. get more food allergies than in other countries, and that even moving here increases your chances of developing one. It’s a big problem, costing the U.S. some $25 billion annually, not to mention the human suffering and, in the worst cases, fatalities. Research published last May in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology reports that 3.6% of us have some kind of food allergy, with women more commonly affected at 4.2%, and men at 2.9%. We’re talking about reactions to shellfish, fruit or vegetables, dairy, tree nuts, additives, grains, and that frightening, even deadly, allergy so common in children, peanuts. (Fortunately, there may be good news for that last group, as we’ll see.)

It seems likely things are getting worse, not better

It’s hard to tell if things are generally getting worse or not since the new research uses a different methodology than previous studies have, and the new report’s authors consider their data more trustworthy. A study released in 2014, for example, found that there was a significant increase since 2006 in U.S food allergies, up to 5% for adults and 8% for children, which makes it sound as if the new study’s statistics mean things are getting better. “However,” as one of the authors of the new research, Li Zhou notes, “most studies reporting food allergy epidemiology use cross-sectional surveys, a method often limited by small sample size and selection bias.” In addition, most focus on a particular allergy or allergy group. The new research instead leverages the information in allergy modules built into electronic health records. This data is at least semi-standardized and allows more useful population-based estimates. Supporting the idea that allergies are increasing, food-induced hospitalizations have increased over the last decade from 0.6 per 1000 patients to 1.3 per 1000 patients. That’s more than double.

(wp paarz)

The 2013 study looked at the health records of health records of 91,642 American children aged 0 to 17. Of particular interest were America kids who’d been born outside the country. They found that “children born outside the United States have a lower prevalence allergic disease that increases after residing in the United States for one decade.” This means that once they moved to the U.S., the incidence of food allergies went up! (No studies have been done that suggest that moving out of the U.S. reduces food allergies.)

What is it about the U.S that’s causing so many food allergies?

It’s not clear what’s going on, though there’s a good-sized list of conditions that can promote immune-system issues such as food allergies, and they’re all present in the States. These include:

What can be done?

Well, we already understand that cleaning up our environment is high up on our collective to-do list, as is taking household toxins more seriously. On that last item, consider going with products formulated to be less toxic such as those at health-food stores, or make your own. Vinegar, water, and alcohol make a very effective all-purpose household cleaner.

Apparently, antibacterial soaps are more futile than you might think — according to the FDA, all the good they do is undone in a few minutes — and maybe we should be less obsessive doubt their use. Experts say just washing your hands with soap and water is just as effective. Junk food? Don’t eat it, or try at least cutting back. Consider adding some anti-allergy foods to your menu. As far as genetics and bad luck go, well…

Peanut allergy relief at last?

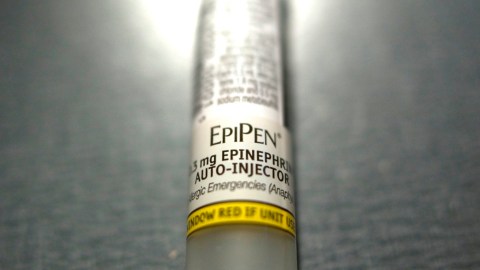

Peanut allergies are terrifying. In a seeming heartbeat, a person can go from normal to intensive care as a result of their immune system’s extreme reaction to the nuts. Parents with peanut-allergic kids carry EpiPens® in case of exposure so that an emergency dose of epinephrine can be quickly administered to bring the child’s reaction under control. Schools also keep them on hand, in addition to being careful to maintain peanut-free zones. These allergies sometimes go away as children grow up, but the opposite is also true: A person can develop a peanut allergy later in life. It’s not clear why this is so.

What makes peanuts so problematic is not totally certain either, but some, like Robert Wood of Johns Hopkins, speculate it has to do with the several proteins they contain that aren’t found in most other foods. It may also be that roasting peanuts changes the proteins’ molecular structure to make them even more provocative to a person’ immune system.

There’s a considerable amount of debate about when it’s safe to even try out peanuts on a child. Conventional wisdom said that children under 3 should be kept totally away from them. However, now, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Institutes of Health both advocate starting children on peanuts as young as four months so the kids have a chance to learn to tolerate them. Peanut allergies, by the way, are one of the allergies experienced more frequently in the U.S. than elsewhere.

For people who have peanut allergies, unfortunately, vigilance has been the only strategy. Now, however, a company called Aimmune Therapeutics has announced the completion of a year-long Phase 3 clinical trial involving 496 kids aged 4 to 17. Half the kids were administered the company’s AR101 pills containing increasing amounts of peanut protein powder up to 300 milligrams, the equivalent of one peanut. (The other kids were the control group and given placebos.) In the end, 67.2 percent of the AR101 group could handle a 600-milligram dose, or up to 1,043 milligrams over the course of 2.5 hours without ill effect. Only 4 percent of placebo patients could do the same. The leader of the study, A. Wesley Burks, shared his excitement: “It’s great to have patients go from managing to tolerate at most the amount of peanut protein in a tenth of a peanut without reacting to successfully eating the equivalent of between two to four peanuts with nothing more than mild, transient symptoms, if any at all.” These results are definitely promising, and the company has three follow-up Phase 3 trials currently underway.