What are We Doing to Prevent the Next Epidemic?

Most people carry on their daily lives buoyed by a false sense of security. Once in a while, something comes along and shakes them out of it. The world was gripped recent by the Ebola epidemic in West Africa that took the lives of tens of thousands. But this is not a new illness. The first recorded Ebola outbreak was in Zaire (presently the DRC) back in 1976. Zika virus, admittedly less of an issue unless one is planning to have children, is the pandemic de jure. It was first discovered in Uganda in 1948, and the first major outbreak appeared in Brazil in the 1960s. These diseases are not new.

Yet, research dropped off when they were no longer an eminent threat. Lots of other potential epidemic-causing illnesses have waxed and waned in the news cycle over the years. These include swine flu, bird flu, MEARS, SARS, West Nile Virus, and so much more. Then there are ever present concerns such as antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Even so, when epidemics fade out of the limelight, the overarching theme seems to be that science prevails, and we are lulled back to sleep.

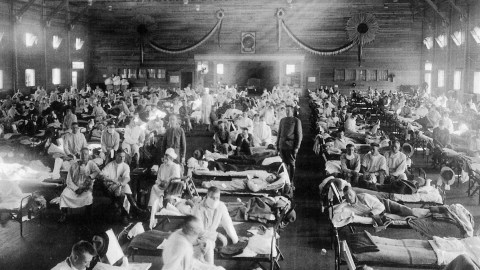

The past teaches a different lesson, that epidemics are no joke, and if left unchecked, can spread into a pandemic quickly, laying waste to whole populations and changing the course of history. Over 75 million were wiped out by the bubonic plague, one-third of all of Europe at the time. Around 95% of the population of the America’s was decimated by the arrival of Europeans, the majority of which were snuffed out by small pox and other such diseases. As recently as 1918, a mere three or four generations ago, between 30 and 50 million worldwide were wiped out by the 1918-1919 flu pandemic. Today, we even have a resurgence of whooping cough and even measles—an illness that was all but wiped out in the year 2000. So how prepared are we for the next epidemic or even pandemic?

Dr. Ken Stuart is the founder and a professor at the Center for Infectious Disease Research at the University of Washington, Seattle. In a recent NPR interview, Dr. Stuart admitted that little research is done on potentially harmful diseases until thousands of people have already become infected.Due to this, U.S. scientists are starting from scratch with the Zika virus. They are playing catch up.

Dr. Stuart recommends setting aside resources to be proactive. “Much of the funding that’s devoted to infectious diseases today is in reaction to outbreaks and therefore we’re not generally prepared to respond quickly,” he said. Dr. Stuart did say that there is continual analysis on how funding agencies operate. There are also ongoing conversations between the federal government and private organizations.

Peter Daszak is the president of the EcoHealth Alliance—a nonprofit concerned with global health. Daszak says that today we are at greater risk of a full-blown pandemic than at any other time in history. He blames the ease of international travel and global commerce.

Spraying for mosquitoes to stop Zika’s spread.

At least in developed countries we have good sanitation, a solid public health infrastructure, which can identify and stop outbreaks, and know how to treat victims, institute quarantines, and put in place other measures to stop worrisome diseases from spreading. In developing nations with fewer doctors and less developed sanitation and healthcare systems, epidemics run rampant with little to stop them.

Today, it is possible to locate where a disease originates and who the possible candidates are to acquire and spread the contagion. There are two major kinds of diseases that can cause an epidemic. The first is from microbes who inhabit a human host. These are more easily contained. The second and more dangerous is those that come from an animal reservoir. They crossover and start infecting humans. This happens mostly in a tropical regions inhabited by developing countries where the animal-human contact rate is high. Once it attaches to a human host, it spreads person-to-person, gets into the city, and from there can spread to other regions, becoming an epidemic or other countries, creating a pandemic.

There is a lot emergency managers and public health officials can do to tamp down an outbreak once it has started. Preventing the next one from occurring however will mean more investment in research, as well as strengthening the public health infrastructure and healthcare systems of developing nations. Particular regions of concern include Africa, Central Asia, and Latin America.

Many countries have improved their public health systems on their own such as Ethiopia and Vietnam. And the U.S. has pledged to help 30 countries catch up. Is this enough? And what about more funding for proper research? While these efforts are helpful, they may not be enough. And proper investment and the allocation of more resources seems less than forthcoming.

Learn more here: