Uncontacted tribes: What do we know about the world’s 100 hidden communities?

On July 1st, 2014 seven members of an Amazon tribe emerged from the jungle and made their first contact with the rest of the world—out of dire and tragic necessity. Despite 600 years of Portuguese-Brazilian history, this tribe only came out to interact with their new neighbors now, and we discover more things about uncontacted tribes all over the world every day—which is not necessarily a good thing.

Uncontacted Peoples

According to Survival International somewhere around 100 so-called uncontacted peoples still exist. The estimates for how many such peoples there are can vary dramatically. For example, Brazil claims to have 77 uncontacted peoples living in the Amazon Rainforest, while National Geographic claims there are 84. When the estimates of uncontacted peoples are taken together and compared, around 100 tribes worldwide is a reasonable answer to give, though the real number is likely higher. Sources for these numbers include observations from aircraft flying over the isolated regions and accounts by contacted peoples living nearby.

“Uncontacted” is a bit of a misnomer, as it’s likely that even the most isolated tribe in the world has interacted with outsiders in some way, whether face to face or by exposure to modern artifacts such as planes flying overhead and inter-tribal trading. However, they are unintegrated into global civilization, retain their own cultures and customs, and can have little interest in communication with the outside world—or too much fear. “They know far more about the outside world than most people think,” Fiona Watson, research director forSurvival International, told BBC. “They are experts at living in the forest and are well aware of the presence of outsiders.”

Where do they live?

Darkened areas indicate regions where uncontacted peoples still live. (Wiki Commons)

As you can see on this map, the tribes live in some of the most difficult-to-reach places in the world, such as the deep interior of the Amazon, the Congo, and the mountains of New Guinea. Two groups are known to live on islands off India.

Why don’t they come out to visit?

The reasons why a group of people might want to remain isolated can vary, but in many cases, it is just that they want to be left alone. Others may have fled into hiding long ago to escape atrocities. Fear is also suggested as a primary motivation by anthropologist Robert S. Walker of the University of Missouri. In the modern world, their isolation can be romanticised as defying the forces of globalization and capitalism, but as Kim Hill, anthropologist at Arizona State University, puts it: “There is no such thing as a group that remains in isolation because they think it’s cool to not have contact with anyone else on the planet.”

Why don’t we visit them?

Technically speaking, most of these tribes have been visited in some way. The so-called “most isolated tribe in the world” (more on that later) was first contacted in the late 1800s by the British Raj, though they have remained extremely isolated ever since. Brazil conducts flyovers of many tribes not only for anthropological curiosity but also to assure that illegal logging is not taking place, and to confirm survival after natural disasters. Many of those tribes in Brazil have items that originated far away and were obtained via trading with other tribes.

The tribes have rights to self-determination and to the land they live on. As the arrival of outsiders would dramatically change their way of life no matter what they might desire, it is thought best that the outside world should stay away so those peoples can determine their own futures.

Historically, tribes that have been contacted have done poorly in the period immediately afterward and the decision to make contact would perhaps lead to more suffering than it is worth in the short run, as many tribes are stricken by illness right after the first contact.

Their isolation causes them to lack immunity to many common diseases, and there is a history of first contacts resulting in epidemics, even to this day.

Should we contact them?

Well, the arguments against visiting them should be pretty clear after reading the previous paragraph. However, a couple of arguments do exist for the other side as well. Most notable is the argument anthropologists Walker and Hill make in Science, that, “isolated populations are not viable in the long term,” and, “well-organized contacts are today both humane and ethical. We know that soon after peaceful contact with the outside world, surviving indigenous populations rebound quickly from population crashes.”

This argument is rejected by most supporters of indigenous rights and is somewhat lacking in supporting evidence. An example of what can happen will be discussed below in the section about Brazil.

Who are they?

Below are five uncontacted and recently contacted tribes. They were selected for geographic diversity and on the availability of information. Much of this information can be taken with a grain of salt, as it is partly based on distant observation.

Sentinelese

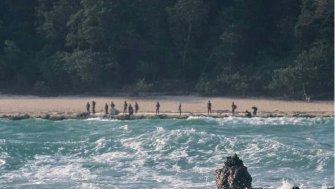

The Sentinelese as seen from a distance (Survival International).

“The most isolated tribe in the world” lives on the Andaman Islands off India. Contacted by the Raj in the 19th century, the tribe has remained isolated and hostile to outsiders ever since. The last official attempt at contact was in 1996; no further attempts have been tried, not only to protect the tribe from disease but also because they have a tendency to shoot arrows at anybody who gets too close.

They remain a hunter-gatherer society with no known agriculture. They have metal tools but can only fashion them out of the iron they recover from nearby shipwrecks. They have been isolated for so long that their language is not mutually intelligible with their nearest neighbors and remains unclassified, suggesting hundreds if not thousands of years of isolation.

The common estimate for the Sentinelese population is around 250.

Jarawas

(Gethin Chamberlain)

Another isolated tribe in India, they also live on the Andaman Islands. They are a self-sufficient hunter-gatherer society and are, by several accounts, rather happy and healthy this way.

In the early nineties, the local government presented a plan to bring the tribe into the modern world but has backed off from this plan as of late. In 1998, members of the tribe began to visit the outside world. Recently more communication between the Jarawas and outsiders has taken place due to the increased settlement near their villages.

This contact caused two outbreaks of measles among the tribe, who had no immunity to it. The tribe is also increasingly subject to visits by misguided tourists and increased settlement near their ancestral home. Government interest in encouraging the tribe to adapt to a more modern lifestyle waxes and wanes.

The population is estimated to be near 400.

Vale do Javari

A member of the recently contacted Matis tribe of Brazil. (Getty Images)

The Javari Valley in Brazil is an area the size of Austria which is home to approximately 20 indigenous tribes. Of the 3,000 persons estimated to live there around 2,000 of them are thought to be “uncontacted”. The information on these tribes is fleeting, but evidence suggests they utilize some agriculture alongside hunting. They have metal tools as well as metal pots they acquired by trade.

In the 1970s and ’80s, it was the policy of the Brazilian government to contact isolated tribes for their benefit. The story of the Matis tribe of this region stands out. As a result of the diseases they were introduced to, the tribe saw three of its five villages wiped out, and their population dropped drastically. The Brazilian government no longer engages in this behavior.

The threat to this population now comes from miners and loggers.

New Guinea

An elderly member of the Dani People (Getty Images).

Information on these isolated tribes is fleeting, as the Indonesian government has done a good job at keeping people out of the highlands. However, some tribes have been contacted over the last century while remaining fairly isolated and retaining their traditions.

One example is the Dani people and their story. Located in the heart of Indonesian New Guinea, the tribe has contact with the outside world but retains their customs. They are well known for their use of finger amputation to remind them of the departed and an extensive use of body paint. While the Dani have been in contact with the rest of the world since 1938, they can offer us a glimpse of the people we have yet to meet.

The Congo

Many of the forest-dwelling peoples in the Congo have been contacted infrequently over the last century. However, it is supposed that many uncontacted tribes still exist. The Mbuti, a ‘pygmy’ people, a contacted but isolated case which can give us an idea of how the uncontacted tribes may live.

The Mbuti are hunter-gatherers who see the forest as a parental figure that provides them with everything they require. They live in small, egalitarian villages. They are largely self-sufficient, but they do engage in trade with outside groups. Their way of life is at risk due to deforestation, illegal mining, and genocide being carried out against pygmies.