Study: Students infected with ‘cat parasite’ more likely to major in business

A new study shows that U.S. students infected with theToxoplasma gondii parasite are more likely to be majoring in business studies.

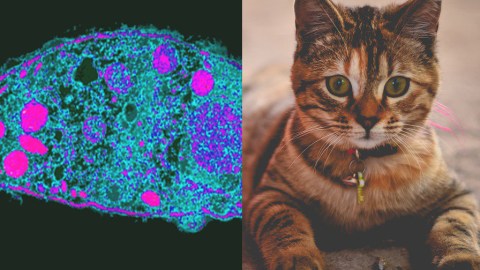

Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) is a one-celled parasite that’s carried by cats. It infects as much as one-third of the world’s population, often after people come in contact with cat feces. T. gondii can cause toxoplasmosis, a potentially deadly disease that’s especially threatening to pregnant women and those with compromised immune systems. However, most infected people will never experience symptoms.

At least, not obvious ones.

T. gondii, which has been called the “mind-control” parasite by some, has in recent years become the main villain of a strange theory, one which argues that the parasite is subtly altering connections in our brains, “changing our response to frightening situations, our trust in others, how outgoing we are, and even our preference for certain scents,” as Kathleen McAuliffe wrote for The Atlantic.

In the new study, published in Proceedings of Royal Society B, researchers examined 1,300 American university students, finding that those who’d been exposed to T. gondii were more likely to be majoring in business studies. Specifically, the infected students were more likely to pursue business management or entrepreneurial activities.

Pixabay

The researchers also found that countries with higher levels of T. gondii infection also show higher levels of entrepreneurial activity, even when controlling for other economic factors. They suggest the reason for this is that T. gondii might somehow turn off the ‘fear of failure’ setting in our brains.

This fearless mindset can benefit entrepreneurs by encouraging them not to shy away from high-risk, high-reward situations. But the researchers also noted the dangers of this risky behavior, citing how most business ventures fail, and how past experiments have shown that the parasite can strip rats of risk-evaluating abilities, putting them in life-threatening situations.

One study, for example, describes how rats infected with T. gondii were no longer scared off by cat urine—they were instead sexually aroused by it.

“We report that Toxoplasma infection alters neural activity in limbic brain areas necessary for innate defensive behavior in response to cat odor,” wrote the authors of the study published in PLOS ONE. “Moreover, Toxoplasma increases activity in nearby limbic regions of sexual attraction when the rat is exposed to cat urine, compelling evidence that Toxoplasma overwhelms the innate fear response by causing, in its stead, a type of sexual attraction to the normally aversive cat odor.”

Other studies have linked T. gondii to mood disorders and behavioral changes, including rage intermittent explosive disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, slower reaction times and suicide. Still, some scientists argue that we shouldn’t jump to conclusions about the parasite because much of the research conducted on T. gondii was conducted unreliably.

But Jaroslav Flegr, a biologist who’s perhaps done more than anyone to advance the theory that parasites could be quietly pulling the strings of our behavior, thinks there’s a different reason why scientists are quick to doubt the body of research.

“There is strong psychological resistance to the possibility that human behavior can be influenced by some stupid parasite,” he told The Atlantic. “Nobody likes to feel like a puppet. Reviewers [of my scientific papers] may have been offended.”