Prime numbers aren’t so random after all

Prime squares ( Flickr user Mark)

- Large prime numbers occur in a natural-looking pattern

- The apparent randomness of prime numbers have long fascinated mathematicians

- A thrilling discover that ties math and nature together

They’ve long fascinated mathematicians: prime numbers. They’re numbers indivisible by any number other than themselves or 1, and they occur ever-more randomly as numbers increase in value. As mathematician R.C. Vaughan put it: “It is evident that the primes are randomly distributed but, unfortunately, we do not know what ‘random’ means.”

Or at least they’ve always seemed to be random since the ancient Greeks first identified them. Now, theoretical chemist Salvatore Torquato of Princeton has discovered something startling: Large prime numbers actually occur according to a pattern that resembles the atomic structure of quasicrystals.

Cryptography’s not-so-secret sauce

For modern cryptography, prime numbers’ randomness is handy. The ubiquitous RSA encryption algorithm multiplies two very large random numbers in the knowledge that deriving the two original values from their product is a beast of a computational problem. There’s no direct connection between Torquato’s finding and the soundness of cryptography that employs primes — at least not yet. But if they’re not really random, well, maybe down the line it will become a problem. But that’s not the really interesting part.

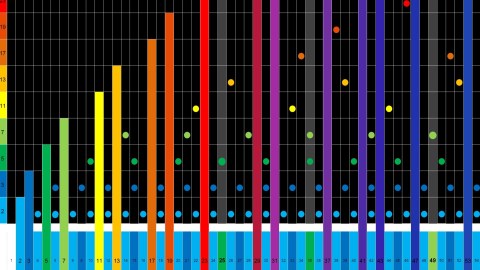

(From Quanta: Lucy Reading-Ikkanda/Quanta Magazine; Crystal diffraction pattern by Sven.hovmoeller; Quasicrystal diffraction pattern by Materialscientist)

Looking at primes in a different way

It was a chemist’s hunch. In chemistry, it’s common to analyze the atomic structure of matter by firing x-rays at it and observing the ways in which the x-rays bounce off the material’s atoms. Different materials produce different x-ray diffraction patterns. Torquato started wondering if there was a way to apply this analytic method to numbers, and what he might see.

Torquato, with grad student Ge Zhang, modeled long prime sequences as one-dimensional strings of particles, with primes represented by small spheres off which x-rays would bounce. It turned out that sequences containing about a million primes — such as the series starting with 10,000,000,019 — were sufficient to generate a meaningful analysis without incurring too much statistical noise. When virtual X-rays were shot at the particles, Torquato and Zhang saw something no one had seen before: Patterns not unlike the ones produced by already-weird quasicrystals, but also different. Still, Microsoft mathematician Henry Cohn tells Quanta, “What’s beautiful about this is it gives us a crystallographer’s view of what the primes look like.”

Quanta’s article on the discovery includes a visual explanation of the ways different materials scatter x-rays.

Numbers made physical

The implication is mind-bending. It’s that prime numbers — non-corporeal digits, after all — can be envisioned as a natural physical system and, as Torquato tells Quanta, “a completely new category of structures.” While it’s long been understood that math can represent and describe a range of natural phenomena and systems, this is the first time primes seem to be themselves one of those systems.

The finding falls in line with research into “aperiodic order” — non-repeating patterns — prompted by the discovery of quasicrystals. As mathematical crystallographer Marjorie Senechal notes speaking to Quanta, “Techniques that were originally developed for understanding crystals … became vastly diversified with the discovery of quasicrystals. People began to realize they suddenly had to understand much, much more than just the simple straightforward periodic diffraction, and this has become a whole field, aperiodic order. Uniting this with number theory is just extremely exciting.”

For Torquato, wherever this leads is secondary. The main payoff is simply being able to get a peek at what goes on behind the curtain with prime-numbers. “I actually think it’s stunning,” he tells Quanta. “It’s a shock.”