How Physicists Smashed the Quantum Light Measurement Limit

How precise can measurements get? Today, we can get down to the quantum level. Once there, only technical limitations stand in the way. One obstacle to greater precision is Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. This states that you can’t simultaneously measure a given particle for position and velocity. It’s either one or the other.

With accuracy in measurement, especially where optics or light is concerned, the goal is to reach the Heisenberg limit. That’s as accurate as you can go to scale while accounting for the energy and equipment used in taking the measurement. This is particularly important with optics. Light particles, photons, are easily absorbed or scattered by equipment.

Like other subatomic particles, photons must obey the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which really puts a damper on taking accurate measurements on the quantum level. For decades scientists have tried to conceive a way to break through the shot-noise limit, or the limit one has when using photons to measure and extract data. Noise is the amount of randomness within photon transmission. Photons can bounce off equipment or disappear. The more noise the less accurate measurements turn out. Now, a team of scientists in Australia have done it. They’ve broken through the shot-noise limit. The findings of this landmark study were published in the journal Nature Photonics.

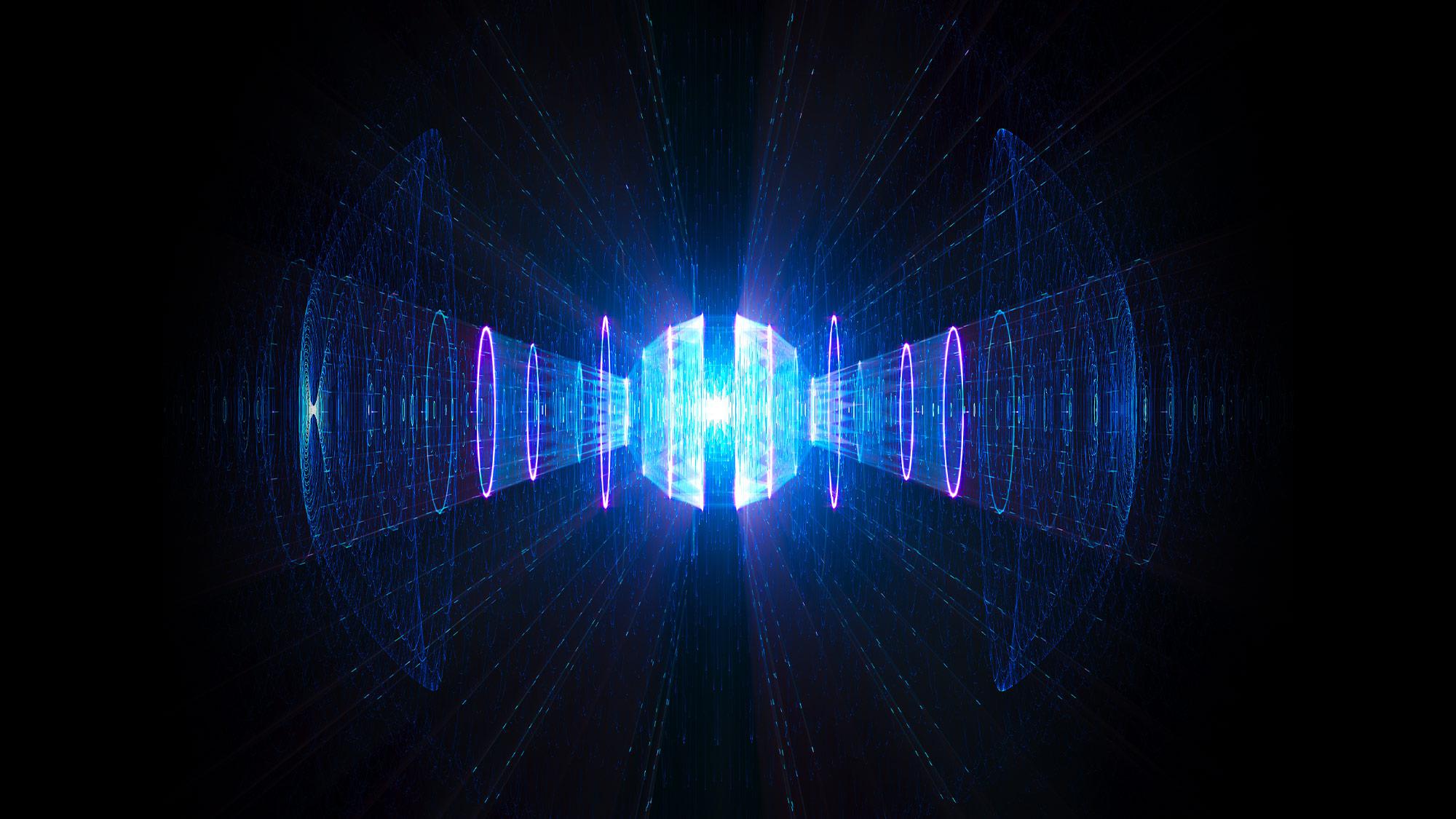

Laser pulses pass through a poled potassium titanyl phosphate crystal, a compensation crystal, a silicon filter, and two other crystals. This allows scientists to filter out noise. Credit: Nature Photonics.

There’s a property called quantum entanglement. When two particles get entangled, they share properties, no matter how close together or far apart. A Chinese team of scientists recently sent a transmission to a satellite some months ago using entanglement, part of the growing field of quantum optics.

Physicist Geoff Pryde and colleagues have now set a record for measuring photons with a level of precision only dreamed of. How they did it was by setting up a series of crystals with properties in each allowing for a certain type of entanglement among pairs of photons. Meanwhile, highly efficient detectors was also able to cut down on random noise. All of this made optical measurements more precise.

They used entanglement to make the photons behave better, most of the time. Pryde said, “What is new here is that we are able to make and measure high-quality photons with high efficiency, and so we can show that the technique really works as described in the theory.” In the future, Pryde and colleagues hope to entangle more than two photons at once and see what results that gives them.

How this will be applied is still not yet known. Scientists are still blown away at the precision they’ve acquired in the newly devised technique. Perhaps it’ll help in the upcoming nanotech revolution or allow us to study very sensitive or volatile substances.

To find out more about the field of quantum optics, click here: