Everybody Lies, But Google May Know the True You.

Everybody lies–to friends, families, and their significant other. But we appear to be brutally honest with our Google searches.

We seem to be typing our deepest, darkest fears into the ubiquitous search box. Unlike the curated and somewhat aspirational characters we portray on social media, our Google searches offer a window into the human psyche.

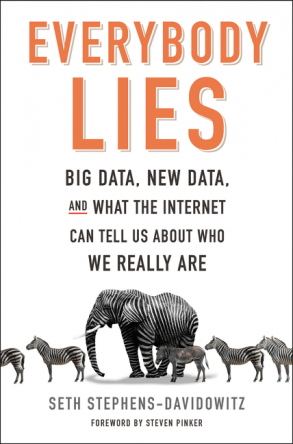

“I think there is something cathartic about telling things to Google that you don’t tell to anybody else,” says Seth Stephens-Davidowitz. Stephens-Davidowitz is the author of the best-selling Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are, and a former data scientist at Google. He is also a Harvard-trained economist who received his BA in Philosophy from Standford; a data scientist attracted to the bigger questions in life.

To the data scientist, our relationship with Google is acting as a digital truth serum of sorts. What we tell others, and perhaps even what we tell ourselves, is different from how we act with a Google search–what comes out when we feel nobody is watching.

Somebody is watching, of course, and Google has made this data (without identifying characteristics of the searcher) available to researchers and other interested parties. For someone like Stephens-Davidowitz, this is a data goldmine. In the process, we can better understand the gulf between our “stated preference” on surveys and social media, and our “revealed presence” that comes out in Google searches.

In other words, there is a dramatic difference between the Facebook self and the Google self. Given that Facebook is for public consumption, the “social desirability bias” kicks in to influence our expressed beliefs towards those seen as more socially acceptable. Google searches, on the other hand, free us from the confines of social expectations–letting out a more authentic, and perhaps less desirable, self. Are we more racist then we project on social media? Do parents treat their sons and daughters differently, while espousing equalitarian beliefs on Facebook?

Do We Have Multiple Personalities Online?

“I think it is interesting that we learn that people have these multiple identities,” says Stephens-Davidowitz. “Cause usually we only see one one of these identities; we see the external identity. With this data we how complicated people are, how they have multiple sides.”

Who Are We? is a question we have been pondering throughout the ages, but the trove of data from Google–and its ability to glean insight into the human condition–is adding an unusual twist. Is the real me what I search for? Is this different from what I express to those close to me?

“I think there are scenarios in which a person can’t say something to a partner, but can say something to Google,” says Stephens-Davidowitz. The author mentions different situations where a person may feel bothered or insecure about something and wouldn’t feel comfortable talking to their significant other about it. A Google search has become a confident of sorts, a non-judgmental therapist. To Stephens-Davidowitz, our Google search habits remind him of a confessional used in Catholicism.

What is the Responsibility of Google?

If Google knows us better than our friends, family, and significant other, that also indicates a potential responsibility. As a de facto therapist or confessional, Google finds itself in a position far more consequential than displaying the best Thai restaurants in town.

Stephens-Davidowitz gives the example of people searching about suicide. Generally speaking, Google takes a completely hands-off approach with their underlying algorithm. Google doesn’t like to mess with the formula, they just like to show you what the formula gives you.

The original search results were hands-off, spitting out the results of the powerful formula as is. “For whatever reason, and this shows a darkness at the heart of the human psyche, some of the top returns initially when searching ‘thinking of committing suicide’ were message boards where people were telling people to do it.” Stephens-Davidowitz continues, “I think Google realized in this case they couldn’t just sit back and let the algorithm show people whatever it was going to show. They had to step in and they put at the top of everything a suicide hotline people could call.”

The Power of Predictive Analytics

It has been five years since the viral story about Target knowing a high school girl was likely pregnant before her own father knew. The girl’s father was unaware of the pregnancy until he received pregnancy-related coupons from Target, which had connected the buying patterns with a likely pregnancy.

Likewise, Stephens-Davidowitz talks about the power of big data to make some pretty remarkable predictions. He discusses the situation where researchers at Microsoft, using data from Bing searches, could determine whether of not someone was going to get the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer a few months before actually receiving the diagnosis.

With great power, however, comes great responsibility. Predictive analytics, especially in the area of health, raise significant concerns about how the data could be used by employers and others. “There are potential pluses to knowing all this,” says Stephens-Davidowitz. “You can potentially diagnose diseases, fight hatred, or help children who are being abused. And there are potential darker sides.”

“I don’t think big data is good or bad,” he says. “Big data is powerful.”

===

Want to connect? Reach out @TechEthicist and on Facebook. Exploring the ethical, legal, and emotional impact of social media & tech. Co-host of the upcoming show, Funny as Tech.