Ukraine: made by Lenin, unmade by Putin?

- One Vladimir created modern Ukraine, and another is now un-creating it.

- But Putin’s dismantling of Lenin’s borders could backfire for Russia.

- Annexation could turn into a Pandora’s box — and a costly paradox.

“Soviet Ukraine is the result of the Bolsheviks’ policy and can be rightfully called ‘Vladimir Lenin’s Ukraine’,” said Vladimir Putin in an hour-long speech on Monday. In that speech, the Russian president announced that he would recognize the independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, two pro-Russian rebel regions in the east of Ukraine. On Thursday, he invaded.

It’s not just Lenin’s fault

So, is one Vladimir merely righting the wrong perpetrated by another Vladimir a century earlier? Not so fast. It’s not just Lenin’s fault. In the “Ukraine is not real” school of thought, currently quite popular in Russia, there are plenty of historical figures to blame for Ukrainians’ inflated sense of self.

“Both before and after the Great Patriotic War,” Putin went on, “Stalin incorporated in the USSR and transferred to Ukraine some lands that previously belonged to Poland, Romania, and Hungary. In the process, he gave Poland part of what was traditionally German land as compensation, and in 1954, Khrushchev took Crimea away from Russia for some reason and also gave it to Ukraine. In effect, this is how the territory of modern Ukraine was formed.”

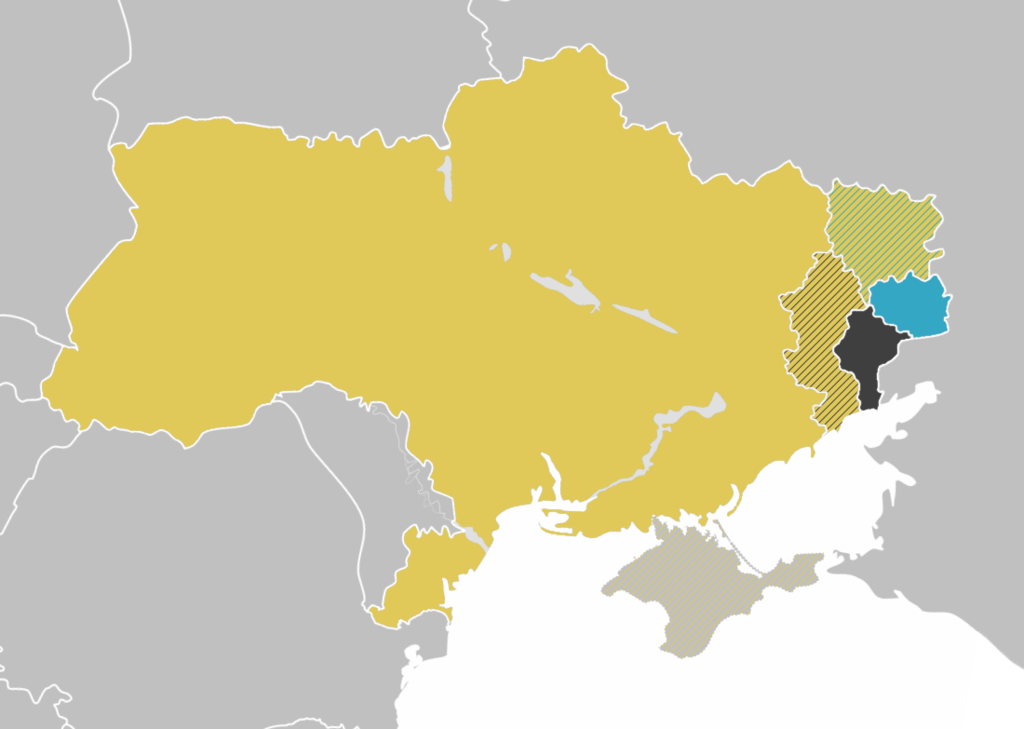

This map, which often pops up in circles of Kremlin apologists, illustrates and elaborates that point.

All you need is Lvov

The map shows the area gifted to Ukraine by Lenin in 1922 (in blue), which contains not just the rebel city of Luhansk, but a stretch of land all the way to the Black Sea port of Odessa, and beyond to the present-day border of Romania.

Also included (in green) are the areas attached to Ukraine by Stalin, before and after the Second World War (a.k.a. the Great Patriotic War in the former Soviet Union). This includes the previously Polish city of Lviv (a.k.a. Lvov, Lemberg, Lemberik, Ilyvo, Lvihorod, and Leopolis — an indication of the area’s many overlapping cultures), and a formerly Austro-Hungarian and Czechoslovakian area known as Transcarpathia (see also Strange Maps #57).

And in purple, there is Crimea. Previously an Ottoman vassal state, the Crimean Peninsula was annexed by Russia in 1783. It remained part of Russia until Khrushchev transferred it from the Russian to the Ukrainian Soviet republic in 1954.

That transfer celebrated the 300th anniversary of “Ukraine’s reunification with Russia” (as per the Treaty of Pereyaslav in 1654) and expressed the “boundless trust and love the Russian people feel toward the Ukrainian people.” It was a natural consequence of the territorial, economic, and cultural proximity between Crimea and Ukraine.

That was the official story. According to this analysis by the Wilson Center, the transfer may very well have been designed specifically to increase the number of Russians in Ukraine, and thus Russia’s hold over it. And it may have been a way to shore up support from Ukrainian Communist leaders for Khrushchev in the ongoing power struggle for the supreme leadership within the USSR.

Chip away the additions by those three Communist leaders and what remains of “Soviet Ukraine” is a much smaller state. The relevant date here is 1654. In that year, Ukrainian Cossacks obtained Russian protection in their fight for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth. The yellow area was added to the now Russian client state of Ukraine following the aforementioned Treaty of Pereyaslav.

The previously independent part is the orange bit in the middle. Not so big now, are you, Ukraine? The larger point made by this map of a much, much smaller Ukraine is that the current version of that country owes its size to Russia, which therefore also has the right to un-create it.

The best neighbor is a small neighbor

In other words, this a license to remold Ukraine’s borders as Russia sees fit. It’s pretty safe to say that, absent the restraints of international law, that is how most large countries feel about their much smaller neighbors.

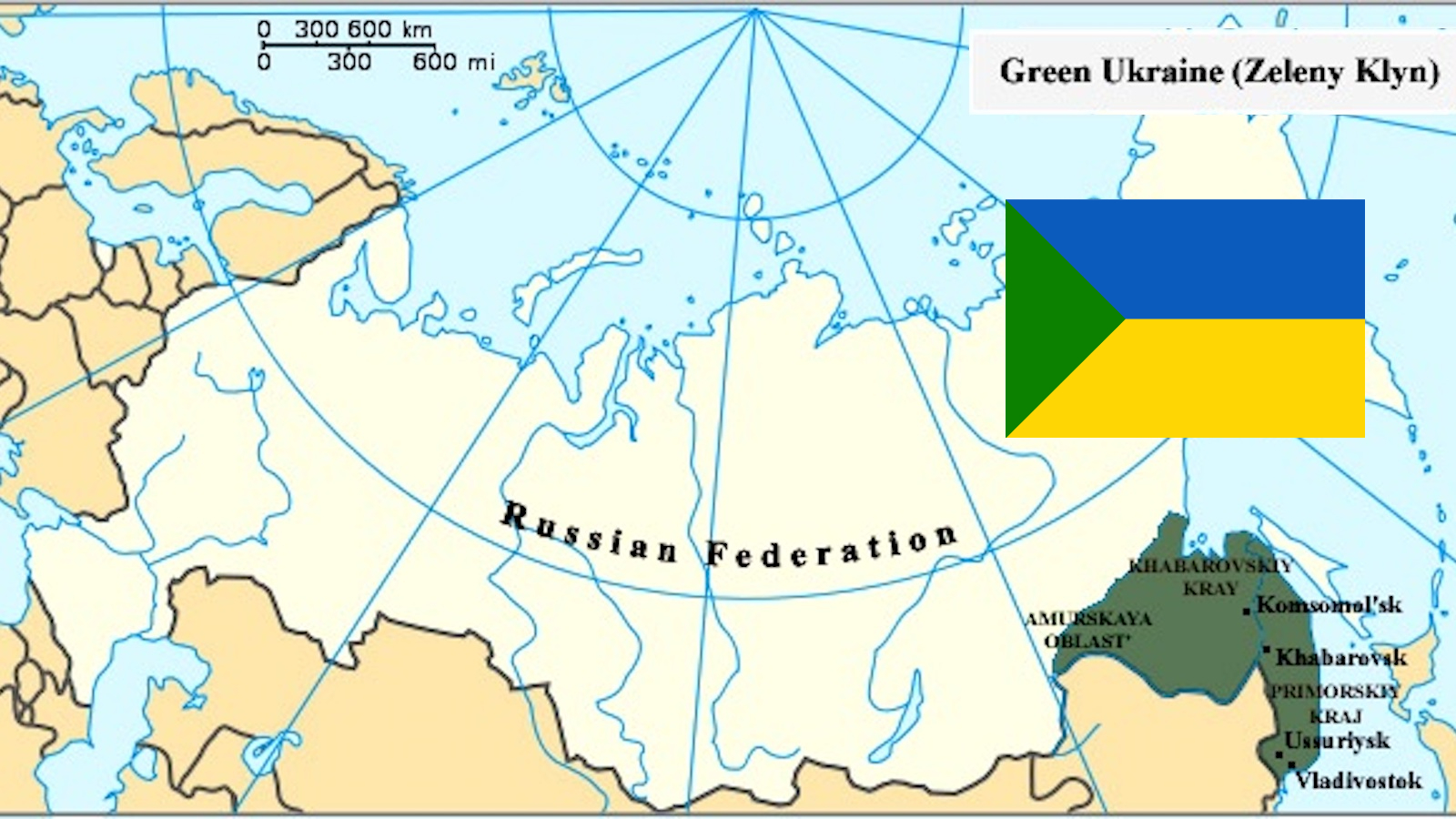

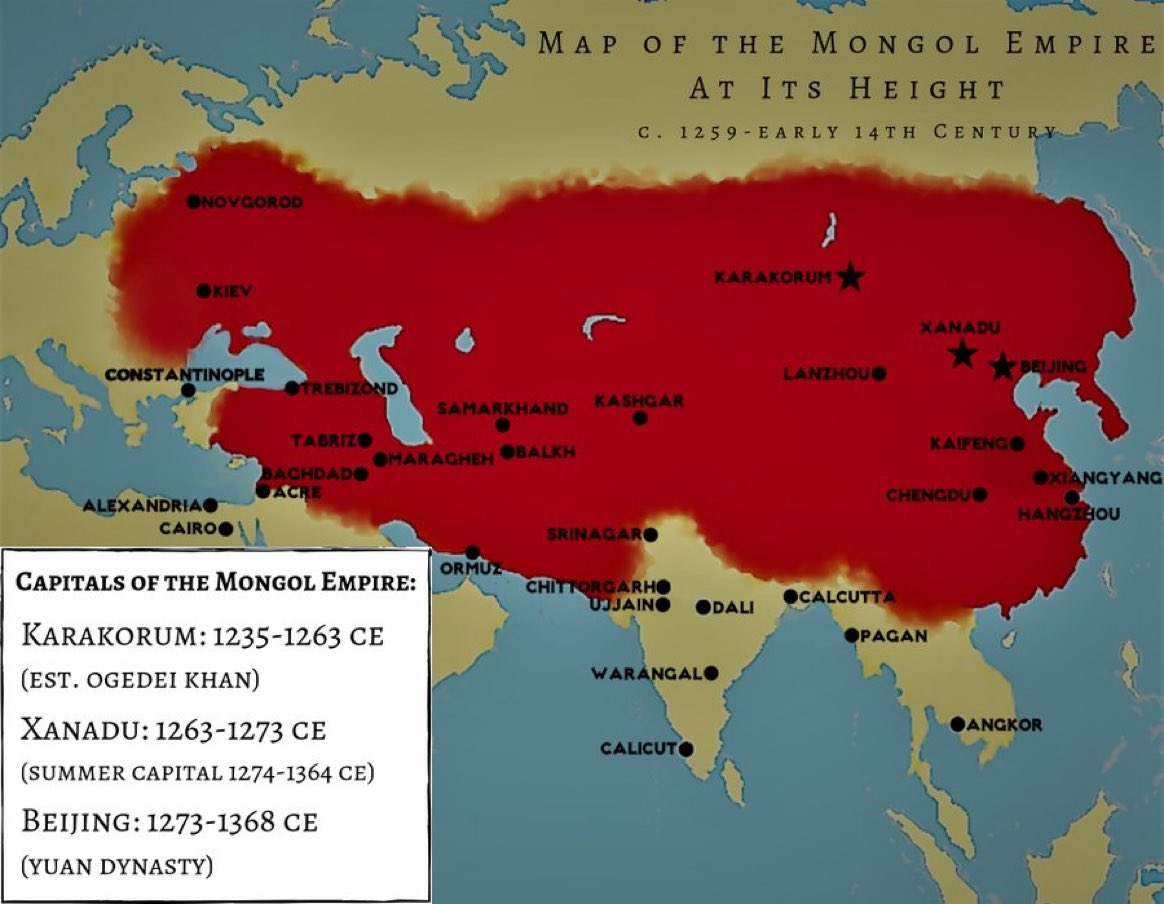

Except that this approach to international borders is against international law, and with good reason. It’s like throwing Pandora’s boomerang. Immediately following Putin’s speech, the internet resonated with claims that the Mongols wanted their Empire back (which at its height included much of Russia) and with questions when Putin would be handing Kaliningrad (once the Prussian city of Königsberg — see also Strange Maps #536) back to Germany.

Given that just about every country harbors some territorial grievance toward its neighbors — yes, even Luxembourg — the proliferation of this attitude would transform the arena of global politics from Twelve Angry Men into Fight Club in no time.

Perhaps the best speech on the matter this week was delivered by Martin Kimani, Kenya’s ambassador to the United Nations. Hailing from a continent whose borderlines were almost entirely drawn by European colonizers, he knows a thing or two about the historic iniquity of the unwanted legacy of empire:

“Today, across the border of every single African country, live our countrymen with whom we share deep historical, cultural, and linguistic bonds. At independence, had we chosen to pursue states on the basis of ethnic, racial, or religious homogeneity, we would still be waging bloody wars these many decades later.”

“Instead, we agreed that we would settle for the borders that we inherited, but we would still pursue continental political, economic, and legal integration. Rather than form nations that looked ever backward into history with a dangerous nostalgia, we chose to look forward to a greatness none of our many nations and peoples had ever known.”

Make Ukraine Greater Again

If all of that sounds a bit too kumbaya for Putin, there is a more Machiavellian motive for not dismembering “Leninist” Ukraine. Just spool back to Khrushchev’s 1954 “donation” to Ukraine of Crimea, which already back then was inhabited by a clear majority of Russians.

If one of the unspoken reasons for that transfer was to tilt Ukraine closer to Russia, then Russia’s 2014 re-annexation of the peninsula had the opposite effect. Detaching Donetsk, Luhansk, and soon perhaps other Russophone and Russophile regions from Ukraine will create a geopolitical paradox for Russia: the more of Ukraine Russia absorbs, the smaller the chance of what remains of Ukraine ever being Moscow-friendly again.

In short: a smaller Ukraine is a more pro-Western Ukraine. If Putin wants his largest Slavic neighbor to be simpatico with its geopolitical aims, perhaps he should take a page out of Lenin’s playbook and Make Ukraine Greater Again.

Strange Maps #1135

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.