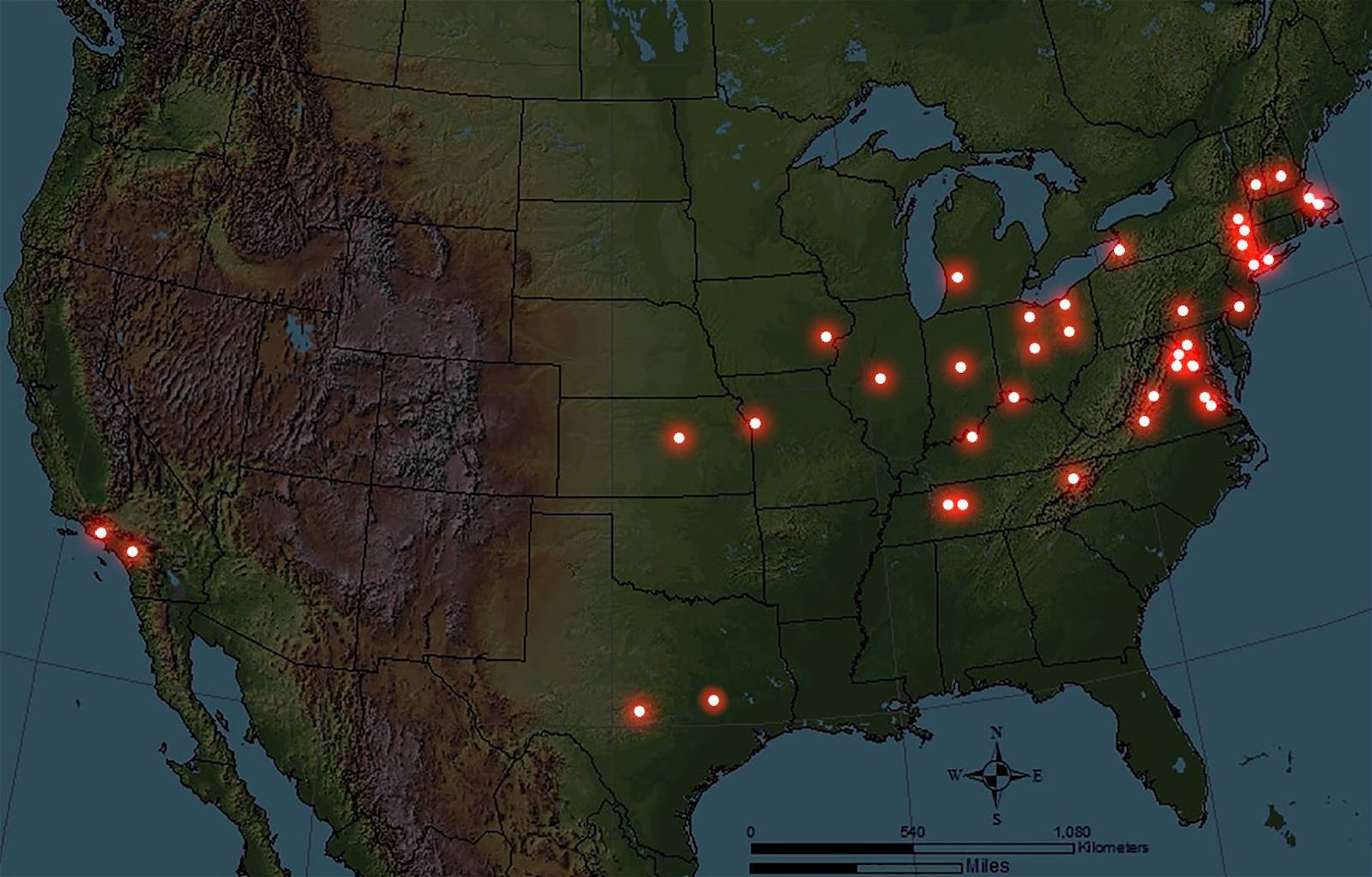

Presidents are not kings. Not only does this affect their powers in office, it also seems to influence their funerary habits — in particular, the distribution of presidential burial sites, as shown on this map. Why? Because dead royalty tends to agglomerate into dynastic clusters. Egypt’s Valley of the Kings has 63 royal tombs from the New Kingdom period alone, which lasted for five centuries until about 1000 BC.

Presidential gravesites: accidental egalitarianism

The Basilica of Saint-Denis, north of Paris, held the remains of 42 French kings until 1793, when French revolutionaries desecrated and ransacked the place. Westminster Abbey, never plundered by archaeologists or insurgents, still houses the bones of 30 English monarchs, from Edward the Confessor (d. 1066) to George II (d. 1760).

America’s dead presidents are spread more evenly — one could almost say, more democratically — across the land. You could argue that this expresses a deep truth about the more egalitarian nature of republican government.

In reality, the U.S. came pretty close to having its own mausoleum crammed with expired heads of state. That trend could have been set, but was ultimately avoided, by what happened to the remains of George Washington. When the first president (and by that time, first ex-president) died in 1799, the fledgling U.S. Congress voted to entomb the Father of the Nation in a burial chamber under the U.S. Capitol.

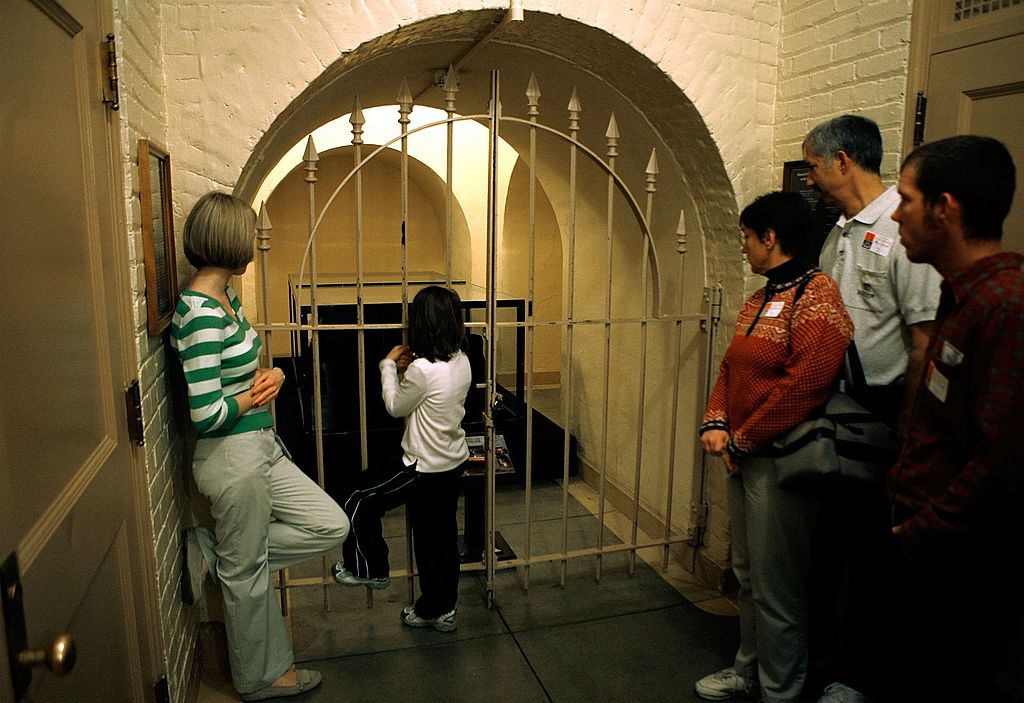

With that building then still under construction, Washington was provisionally interred in the family crypt at Mount Vernon, his Virginia estate, now known as the Old Tomb. His body was kept there in a non-final resting place, while Congress continued to argue over cost and design of the ultimate one.

Stealing Washington’s skull

Things came to a head, literally, when in 1830 a disgruntled ex-employee of the estate attempted to steal Washington’s skull. The crypt was by then so dilapidated that the thief proved unable to identify the right grave and ran off with the skull of a distant relative instead.

Following the incident, Congress again demanded the return of Washington’s bones. But the Washington family took matters into their own hands, thereby profoundly affecting the course of American presidential funerary history. The Washingtons built their illustrious forefather a whole new crypt on the grounds of Mount Vernon — which is as he wanted it, incidentally — and that New Tomb is where his remains remain.

The burial chamber two floors below the Capitol’s Rotunda known as “Washington’s Tomb” has remained empty, and therefore never became the template for subsequent presidential burials. Most of those followed the pattern established by Washington, with U.S. presidents generally choosing their hometowns as final resting places. Hence, there is no American equivalent to Westminster Abbey, or an Egypt-inspired Valley of the Presidents.

Nevertheless, as this map shows, some clustering does occur, albeit at the state level rather than in a royal valley or a dynastic church. Just four states are home to over half of all presidential gravesites.

Woodrow Wilson, the odd one out

George Washington is one of seven presidents buried in Virginia, which is more than in any other state. Next in line are New York with six dead presidents, Ohio with five, and Tennessee with three. Massachusetts, Texas, and California each have two, while 11 states have one each. In all, 38 of the current 39 presidential gravesites are distributed across just 18 states.

The odd one out is Woodrow Wilson (#28, d. 1924), who is entombed in Washington D.C.’s National Cathedral, making him the only president to be buried in the nation’s capital.

A presidential date with death

In the annals of presidential passings, Independence Day has a special place. Not one, but two former presidents died on July 4th, 1826 — exactly 50 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, which they both helped draft. Supposedly, the last words of John Adams (president #2) were: “Jefferson still survives.” If true, he was wrong: president #3 had in fact pre-deceased him by five hours. Five years later to the day, on July 4th, 1831, James Monroe (president #5) died.

No other presidents have died on Independence Day, but July has proved to be the deadliest month for (former) holders of the highest office in the land. No less than seven have breathed their last in the year’s seventh month, while June has claimed six so far. Curiously, no (ex-)president has ever died in May.

Two other presidential pairs died on the same day (although not in the same year): Millard Fillmore (#13, d. 1874) and William Howard Taft (#27, d. 1930), both died on March 8th; and Harry Truman (#33, d. 1972) and Gerald Ford (#38, d. 2006) both expired on December 26th.

The two presidents buried closest to each other are John Adams and John Quincy Adams (#6, d. 1829). The first of two father-and-son duos to hold the highest office are buried together with their wives in the Adams family crypt in the United First Parish Church in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Only two other presidential pairs are buried at the same location, both outdoors. William Howard Taft (#27, d. 1930) and John F. Kennedy (#35, d. 1963) are both interred at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, albeit hundreds of feet apart. Kennedy’s grave is marked by an eternal flame. Taft, in life weighing 330 pounds, in death is haunted by the rumor that he had to be buried in a piano box (which isn’t true, but hard to forget).

Presidents Monroe and John Tyler (#10, d. 1862) are both buried just a few feet apart, at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Presidential trivia with a cartographic dimension

This map adds an interesting cartographic dimension to presidential death trivia: It shows which gravesites are furthest north, south, and west.

Reagan’s (#40, d. 2004) gravesite in Simi Valley, California is the westernmost of the presidential burial sites. The other pin in the Golden State marks Richard Nixon’s (#37, d. 1994) grave, in Yorba Linda.

The southernmost one is Lyndon Johnson’s (#36, d. 1973) in Gillespie County, Texas. A close second is George H.W. Bush (#41, d. 2018), the most recent former president to die, in 2018. He rests in College Station, a bit further north in Texas. Bush, the father in the only other “& Son” presidential franchise so far, has the further distinction of having been the longest-living former president, breaking Gerald Ford’s longevity record to die one year older, at 94 years of age.

The northernmost presidential gravesite is that of Calvin Coolidge (#30, d. 1933), at Plymouth Notch Cemetery in Plymouth, Vermont. A close contender for the title is Franklin Pierce (#14, d. 1869), buried in the Old North Cemetery in Concord, New Hampshire.

So, what about east? The two easternmost dots on this map are father and son Adams, next to each other in their family crypt. No maps are available that show the orientation of these two presidential graves (both are flanked by their wives), so it’s impossible to determine categorically which one completes the most inconsequential of presidential accomplishments: occupying the easternmost presidential burial site.

Anybody reading this near the “Church of the Presidents” in Quincy, MA, please go have a look and help us out!

Stealing Lincoln

Finally, one more thing about presidential grave-robbing. Despite the raid on Washington’s skull, most presidents are buried in relatively unsecured locations. While that may suffice for the more forgettable leaders, it almost proved disastrous in the case of Abraham Lincoln (#16, d. 1865), arguably the most revered of presidents.

In 1876, two Chicago counterfeiters plotted to steal Lincoln’s body from his unguarded tomb in Oak Ridge Cemetery, just outside of Springfield, and hold it for ransom. The expert they asked for grave-robbing tips happened to be a Secret Service informant, otherwise their plan might have worked.

To thwart further attempts, Lincoln’s body was re-buried in a shallow, unmarked grave in the basement of his tomb. It stayed there until 1901, when the Great Emancipator was re-re-buried, this time in a robbery-proof setup consisting of a steel cage covered with 10 feet of concrete.

For a handy overview and photographs of all presidential gravesites, check out this page at PresidentsUSA.net.

For an aesthetic appreciation of presidential graves, from the understated to the overly ostentatious (we’re looking at you, Garfield, McKinley, and Harding!), check out Joey Baker’s ranking over at Media Sandwich. (Warning: his criticism contains profanities.)

Strange Maps #1146

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.