Paris, destroyed: A map of buildings lost to history

Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Following the blaze that ripped through Notre Dame, it feels like Paris had lost a major link to its past.

- But the cathedral is lucky to have survived this far: It was almost torched by revolutionaries in 1871.

- As the world’s first communist revolt was crushed, other Parisian landmarks were set ablaze – many of which were lost forever.

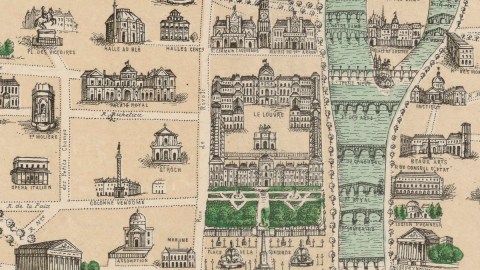

The burning of Notre Dame on April 15th felt like a singular disaster. But Paris has lost countless other monuments before. This map charts one of the darkest episodes in the city’s history.

Twenty-two historical sites destroyed during the Commune.

Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Paris in ruins

During the Commune in 1871, dozens of historical buildings were set ablaze. Some were restored to their previous glory, others were replaced by buildings of a radically different design, and some have gone forever.

The Paris Commune was a brief but bloody insurrection by the Parisian proletariat. It would later exert a huge influence on communist thinkers like Marx and revolutionaries like Lenin.

Right, the docks or customs at La Villette: “Burned and destroyed on May 27th. Losses at both stores are estimated at 29 million francs.” Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Left, the Vendôme Column: “A memorial to our ancient glories, this column in 1810 had replaced the ruins of the pedestal of the statue Louis XIV. It was destroyed on May 15th, 1871.”

Dining on rats

The context for the uprising was the Franco-Prussian War, which by late 1870 was going horribly wrong for France: Napoleon III had capitulated to the Prussians, causing the collapse of the Second Empire. The fledgling Third Republic struggled to keep up the fight.

The Prussians advanced to Paris and besieged it for four months. The French government had abandoned the capital, fleeing first to Tours, then further south to Bordeaux. During the freezing winter of 1870-’71, famished Parisians ate the animals in the zoo, and then resorted to dining on rats.

Right, City Hall: “The most important building, from an artistic point of view. The first stone was laid in 1532. It was only completed in the reign of Henry IV. Enlarged in 1841, under Louis-Philippe. Completely destroyed in 1871.” Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Left, Rue de Rivoli, ‘Le Bon Diable’: “Fabric warehouse frequented by the working classes. Completely destroyed as well as several adjacent houses.”

Raising the red flag

Paris’ main defense was the National Guard, drawn largely from the politically radicalized working classes. Calls for the establishment of a “socialist republic” in the Commune of Paris grew louder and louder.

After France’s capitulation in January 1871, the Commune established a Central Committee that refused to accept the French government’s authority. Revolutionary troops seized key government buildings and raised the red flag over the Hôtel de Ville.

Right, the Legion of Honour: “This palace dates from 1786. Its large living room was decorated by Bocquet, Louis XVI’s favorite painter. The archives have been destroyed. There is little damage on the outside, but little remains on the inside.” Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Left, Ministry of Finance: “Built in 1811 on the site of the gardens of Les Feuillants Convent, this building is now completely collapsed. It was one of the first to be burned, on 23 May 1871.”

La semaine sanglante

For a few months, the Paris Commune ruled itself, decreeing a multitude of socialist, secularist, and anti-imperialist measures, until the army re-established the government’s authority during the Semaine Sanglante (the Bloody Week), which began on 21 May 1871.

One of the Commune’s decisions was to pull down the Vendôme Column as a “monument of barbarism” and a “symbol of brute force and false pride.” The original proposition was by Gustave Courbet, the painter.

Right, Court of Audit: “The interior is completely burned. The restoration of this building is estimated at three million francs. Built in 1807, burned on May 23, 1871.” Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Left, Tuileries Palace: “This is one of the greatest losses for Paris. The main building is no more than a heap of ruins. Burned on May 23, 1871.”

Melted down into coins

The column was destroyed on the 16th of May. After a failed first attempt, it was toppled at 5:30 pm. The column shattered into three pieces, the pedestal was draped in red flags, and the bronze was melted down into coins.

It took France’s “government in exile” some time to gather enough troops to reconquer the capital. A final, bloody assault by the French Army ended the Commune.

Right, Rue du Bac: “The oldest aristocratic families live in this neighbourhood, that’s why it suffered so much. The houses numbered 6, 7, 9, 11 and 13 have been completely burned.” Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Left, the Royal Palace: “The Residence of the Prince Napoleon, this building is totally in ruins. Anne of Austria lived here in 1645, then Cardinal de Richelieu, and then the regent Philippe of Orleans.”

900 barricades

The Bloody Week began on the 21st of May, when the army entered the city walls unchallenged. In the absence of organized resistance, it then took back the city district by district.

In response to the army’s advance into the city on the 22nd of May, up to 900 barricades were hastily erected by the Communards. That afternoon, the first heavy fighting started, with artillery duels between both sides. The National Guard started executing army prisoners, and the other side reciprocated.

Right, St Martin’s Gate: “Having already burned twice, it was completely destroyed on the Boulevard side. Many adjoining houses burned, also in the Rue de Bondi.” Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Left, the Palace of Justice: “The old part of the palace suffered little, but the new part, a masterpiece of architecture, is in ruins. The Holy Chapel was spared but the beautiful paintings by Lhemann and Robert Fleury were consumed by the flames.”

Thick blankets of smoke

On the 23rd of May, the army reconquered the Butte Montmartre, where the uprising had begun. Prisoners were executed en masse. In revenge, National Guardsmen started burning public buildings.

In the early hours of the 24th of May, the Hôtel de Ville, until then the Commune’s headquarters, was evacuated and set ablaze. That day, uncoordinated battles resumed under thick blankets of smoke.

Right, the Bank of Deposits and Consignments: “Located at the centre of the fires, the interior of this building has been completely destroyed, without anyone able to come to its aid. All that’s left are the four walls.” Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Left, conciergerie: “Side overlooking the Quai des Orfèvres. It’s from this building that the orders for so many massacres were given. In many previous reigns it was also in this courtyard that so many innocents were executed.”

More buildings set afire

More buildings were set afire: the Palais de Justice (destroyed save for the Sainte-Chapelle), the Prefecture de Police, the theaters of Châtelet and Porte Saint-Martin, and the Church of St. Eustache.

Fires that started at Notre Dame were extinguished without causing too much damage. By the end of the 25th, the Commune controlled just one-third of the city.

Left, the Arsenal: “Most of this arms and ammunitions dump went up in flames. Some parts of the building were saved, however. Burned on May 24, 1871.”

Right, Place de la Bastile & Rue de la Roquette: “The entrance of the Faubour St Antoine – the capital’s most crowded neighbourhood. The location of frightful events during each revolution. In 1871, there were crimes and massacres from the Rue de la Roquette all the way to Père Lachaise.”

Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Last stand at Père Lachaise

On the 26th, the Army retook the Place de la Bastille and the Buttes Chaumont a day later.

One of the last redoubts of the Commune was the cemetery of Père Lachaise. The last 150 guardsmen surrendered and were shot at what is now known as the Communards’ Wall.

Left, the Lyric Theatre: “One of the most beautiful theatres of our age, where so many artists gave their best. Little damage on the outside, but inside everything has to be restored. Cost of the restoration is estimated at 2 million francs. Burned on May 23, 1871.”

Right, the Attic of Abundance: “This most useful building housed several million francs’ worth in goods, grain, flour, oil, bacon, etc. Built in 1807 and destroyed in 1871, it was 350 meters in length.”

Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

‘Revolutionary government of the future’

The last resistance was mopped up on the 28th. The army counted 877 casualties, and the number of Communards killed was much higher, but the exact number remains uncertain – estimates vary from 6,000 to 20,000 killed.

For Marx, the Commune was the “prototype for a revolutionary government of the future.” Fellow communist theorist Friedrich Engels was the first to call the Commune a “dictatorship of the proletariat,” a phrase later taken up by Lenin and applied to the Soviet Union.

Left, Rue de Lille: “This neighborhood suffered the most. The houses fallen prey to the flames are (…).”

Right, Auteuil Bridge and Station: “Major battle flashpoint, and point of entry for the Army troops into Paris. The bridge had already been badly damaged by the enemy, and finally succumbed under the heavy artillery by the French Army on May 21, 1871.”

Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Lenin, dancing in the snow

The Paris Commune inspired similar workers’ uprisings; first in other French cities, and also later, as far afield as Moscow (1905) and Shanghai (1927 and 1967). Lenin danced in the snow in Moscow when his government was two months old – this meant it had already outlived the Paris Commune. A red banner from the Commune brought to Moscow by French communists in 1924 still adorns his mausoleum.

At Père Lachaise, a plaque commemorates the spot where 147 Communards were executed. After the restoration of the bourgeois regime, Gustave Courbet was ordered to pay for the restoration of the column. He left for Switzerland, never to return. He died without having paid a sou.

Left, Rue Royale: “Once beautiful and rich, this area is now an eyesore, from house number 13 to Faubourg St Honoré. At number 3, everything is burned. The damage is estimated at 700,000 francs. Burned on May 22nd.”

Right, the Red Cross: “Six stores on the corner of the Rues de Grenelle, Sèvres and Cherche midi are totally in ruins. Burned on May 23, despite the resistance put up by several neighbourhood residents.”

Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Propaganda value reversed

For decades, the ruins of the Commune remained visible in the city centre of Paris. In fact, they became popular tourist attractions, just like the ruins of ancient Rome or Greece.

Curiously, the propaganda value of the destruction soon reversed polarity. The Communards had torched grand old buildings as a last, angry act of resistance against the resurgent bourgeois régime.

The charred remains of the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall).

Image: Alphonse Liébert/public domain

The excesses of radicalism

Rather than a rebuke of imperialism and capitalism, the ruins came to be seen as a warning against the excesses of radicalism.

These 22 vignettes of buildings destroyed during the Bloody Week frame a large map of Paris that looks as if the Commune had never happened: the Tuileries Palace is still attached to the Louvre, and the Grenier d’Abondance stands on the river’s edge, stocked with food that will soon end up on Parisian tables.

19th-century Paris, enclosed in its city walls.

Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France

Road map for 19th-century Paris

This map is not just a critique of the destruction wrought by the Communards, it’s also a road map for mid-19th-century Paris. And despite the fact that a number of buildings have been lost to history, it’s still a fairly accurate guide to the city’s architectural heritage today.

Image found here at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (also on the map, by the way).

Strange Maps #976

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.