Happily Obscure: the Kingdom of Macaronesia

No news is good news. As a rule, the world’s attention turns to areas plagued by war, disasters, and other forms of extreme distress. Overall obscurity is a better predictor of gross national happiness than global notoriety [1].

So when the obscure, unfamiliar name of Micronesia – threatened by rising ocean levels – pops up in the headlines, trivially minded people, yours truly included, wonder: Is there also a Macronesia? Because some toponyms just crave an antonym. West Germany required an East Germany. No North Korea without South Korea. Big Diomede Island (RU) lies next to Little Diomede Island (US). So does Micronesia (Greek for “Little Islands”) have a cousin called Macronesia (i.e., “Big Islands”)?

Certainly not in its Pacific neighborhood. Micronesia was named in analogy to Melanesia and Polynesia [2]. But there is no Macronesia nearby — the nearest big islands are simply called New Guinea, Australia and New Zealand. And then of course there is Indonesia, a political rather than a geographic collective toponym [3]. Looking for Macronesia on Wikipedia, the ghost of Clippy suggests: Did you mean Macaronesia? No, I didn’t. But it sounds obscure enough to be interesting.

Melanesia, Polynesia, Micronesia.

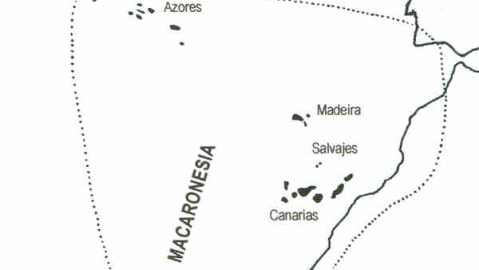

The analogy with Poly-, Mela-, Indo-, and Micronesia suggests Macaronesia is another Pacific archipelago. But almost nothing (or rather, nowhere) could be further from the truth. Macaronesia is the virtual antipode [4] to Micronesia. It’s the collective name for a number of archipelagoes off North Africa’s Atlantic coast, and it is obscure because those islands are hardly ever referred to collectively, except in a biogeographical context.

In its most common definition, Macaronesia consists of four island groups, belonging to three different countries: the Azores, the Madeira Islands [5] (both Portuguese possessions), the Canary Islands (Spain), and the independent archipelago of Cape Verde.

The name refers to the Fortunate Islands, a.k.a. the Islands of the Blessed (makaron nesoi), situated by ancient Greek legend beyond the Pillars of Hercules, in the Atlantic Ocean. As is the case with Atlantis, the precise mix of fact and fiction is hard to untangle in the case of the Fortunate Islands.

Perhaps those Greek legends were based on actual knowledge of the Canaries or other nearby islands. But their location beyond the horizon of the Greek world provided them with mythical qualities: island paradises rich in fowl and flowers, last resting place of heroes. According to Pliny the Elder, the only drawbacks were the “putrefying bodies of monsters, which are constantly thrown up by the sea.”

In later centuries, the Greek legends of happy faraway lands beyond the sea were conflated with similar Celtic legends (Avalon, Tir na nOg), with Viking explorations of Vinland and even with the Antilles.

Macaronesia and its constituent parts.

As a modern term, Macaronesia was first used in the mid-19th century by English botanist Philip Barker-Webb (1793-1854), co-publisher of the Histoire naturelle des Iles Canares.

The term is still used most often in a biogeographical context, to describe the similarities between floral and faunal species found on the islands constituting Macaronesia. For example the laurisilva forests, a type of mountain cloud forest once prevalent throughout the Mediterranean Basin; and the Macaroeris, a genus of jumping spider, named after the islands.

Yet that biogeographical continuity is also disputed. The islands are all volcanic in origin, and were never part of a single continent. They are far apart — almost 3,000 km north to south — with climate types ranging from Mediterranean to subtropical, and enough plant and animal diversity to question the very existence of a separate Macaronesian ‘kingdom’ of species [5].

On the other hand, some biologists posit the existence of a “Greater Macaronesia,” with biogeographical enclaves of Macaronesian-type plants extending to the Iberian peninsula and the Moroccan mainland.

Will perhaps one day those maps stir the heartstrings of Macaronesian chauvinists, eager to turn the taxonomical borders of their kingdom into genuine political ones? There is some indication that Macaronesia is in the process of “conceptual solidifying.” Exhibit one: In 1992, the European Union officialized the concept biogeographical regions, for the purpose of faunal and floral conservation. Originally five, these regions now number 11, and cover Europe beyond the EU, including the Caucasus and Asia Minor. Official European biogeographical regions include the Alpine Region, the Boreal Region, the Pannonnian Region, and the Macaronesian Region (which in this definition excludes Cape Verde).

One version of Greater Macaronesia — including the Moroccan exclave, but excluding the Iberian one.

Exhibit two: A statement on an official Capeverdian government website, dated 2010, relates its government assuming the presidency of the first, two-yearly Cimeira dos Arquipelagos da Macaronesia (CAM; or Summit of the Archipelagoes of Macaronesia), an intergovernmental body aimed at creating “a space for political consultation and development cooperation between the Canary Islands, Azores, Madeira, and Cape Verde.”

Information on subsequent CAMs is missing. And perhaps that is as it should be. At least if Macaronesia wants to remain true to its name: a collection of happy islands, basking in its own obscurity.

Another Greater Macaronesia, with the Iberian pied-à-terre.

Image of Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia found here on Wikimedia Commons. Produced by Kahuora, released into the public domain. Image of Macaronesia and its constituent parts found here on Wikimedia Commons. Produced by ArnoldPlaton, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Image of Greater Macaronesia found here on skyscrapercity.com. Second image found here on elguanche.info.

Strange Maps #709

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] As Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian wrote in his Fables (1792): “Pour vivre heureux, vivons caché” (“To live happily, let us live hidden away”). Quite so. Who has ever heard of him?

[2] Ancient Greek for “Black Islands” and “Many Islands” respectively. Which is strange, as there were absolutely no ancient Greeks anywhere near any of these archipelagos.

[3] “Indonesia” is a political term, not a geographical one. Geographically, Indonesia is considered part of South East Asia. As it happens, Micronesia itself is a good example of the distinction between political and geographic divisions. Geographically, Micronesia is a subregion of Oceania. Politically, this subregion is made up of six sovereign states — only one of which is the Federated States of Micronesia. The other five are: Nauru, Palau, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands and the U.S. (by way of three territories: Guam, Wake Island and the Northern Marianas).

[4] Give or take one or two thousand kilometres. See #104.

[5] Includes Madeira, the island of Porto Santo, and the uninhabited mini-archipelagoes of the Ilhas Desertas and the Ilhas Selvagens.

[6] More on that in Macaronesia, a Biogeographical Puzzle.

[7] See here.