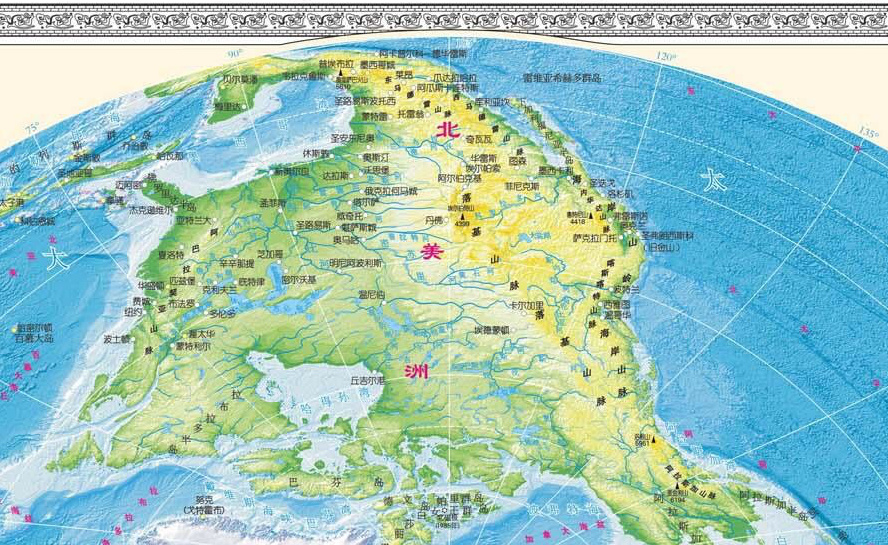

The world map of the future might be vertical

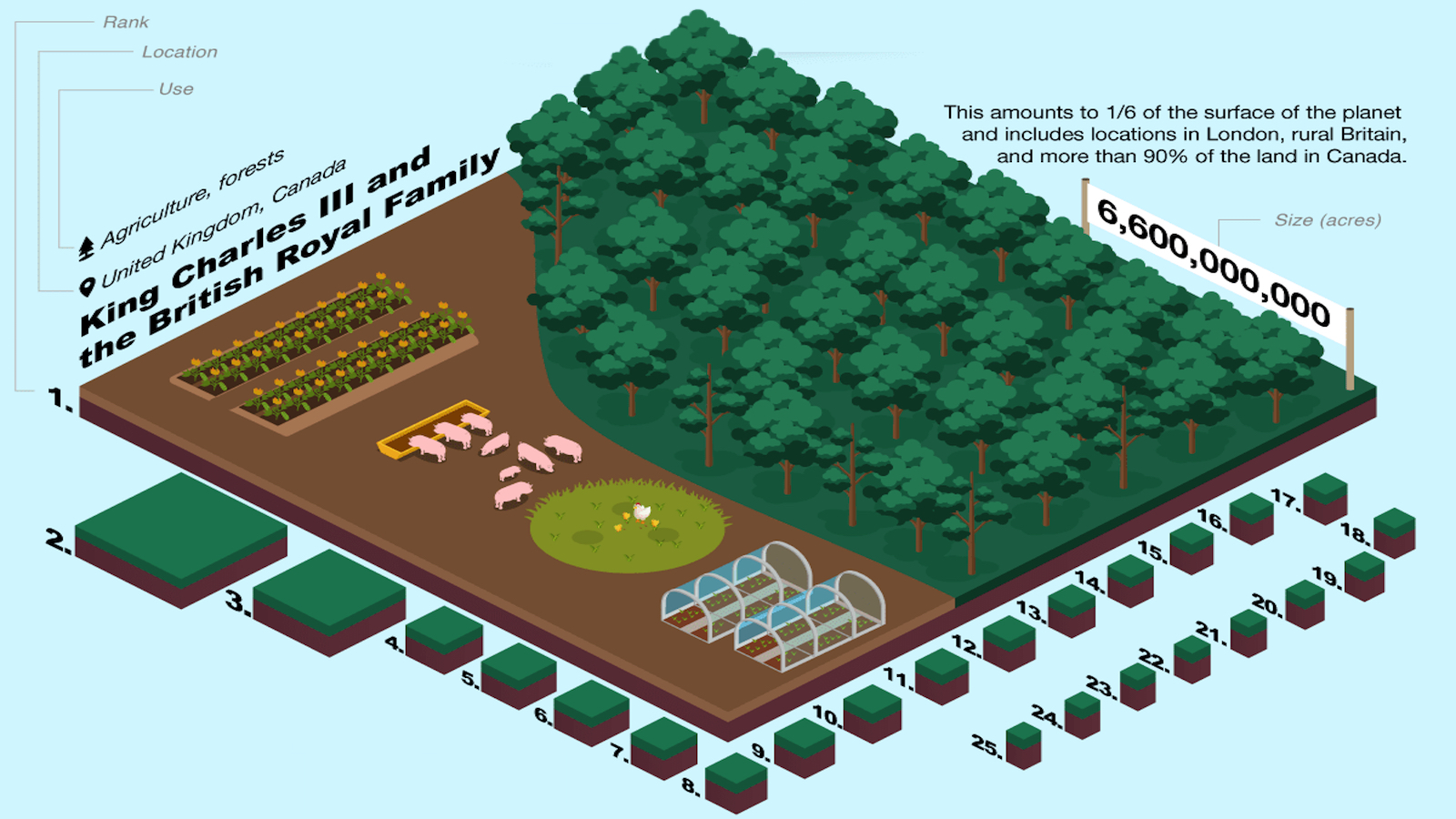

Image: Prior Probability

- Europe has dominated cartography for so long that its central place on the world map seems normal.

- However, as the economic centre of gravity shifts east and the climate warms up, tomorrow’s map may be very different.

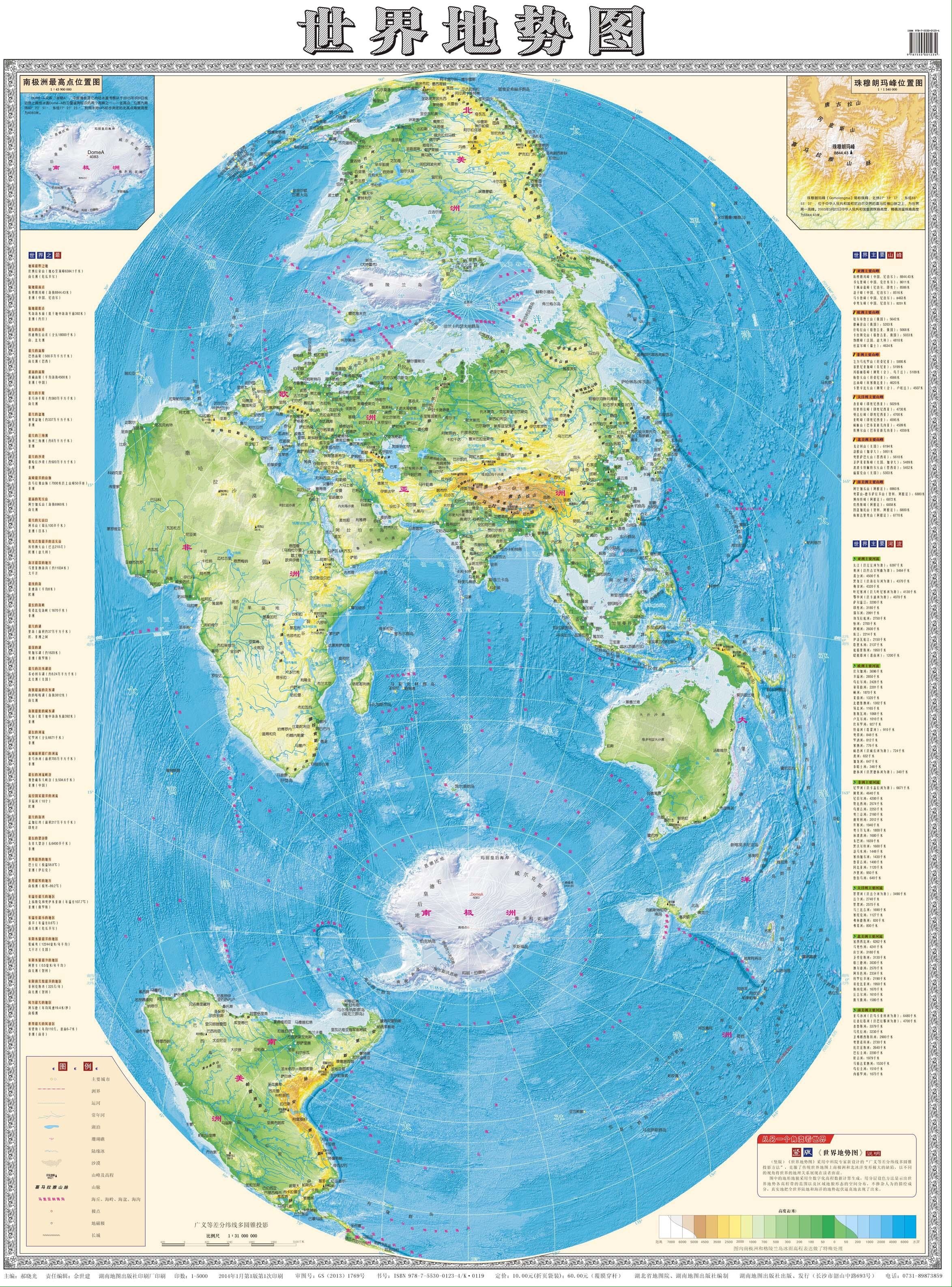

- Focusing on both China and Arctic shipping lanes, this vertical representation could be the world map of the future.

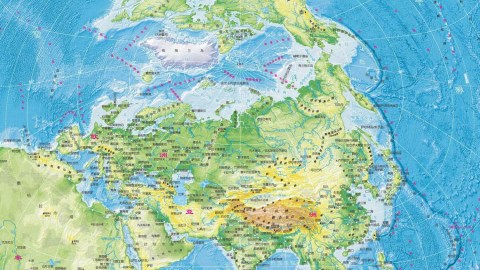

The world, but not as we know it

Europe is tucked away in a corner, an appendage of Asia dwarfed by neighboring Africa. North America is stood on its head, facing the rest of the world from the top of the map — cut off from South America, which cuts a solitary figure at the bottom. Africa is justifiably huge, but equally eccentric.

The eye scouts elsewhere for a place to land: not the Indian Ocean, which dominates the middle of the map, but some terra firma. Antarctica and Australia are too small, mere stepping stones for the land mass of Asia. Ultimately our gaze is drawn toward China, the lynchpin of this unfamiliar world.

Managing to leave both poles intact, this “vertical” world map is about as far away as you can get from the classic Mercator projection, which slices up both, giving center stage to a puffed-up Europe. Perhaps this new map will become more familiar soon: It may do more justice to the world of the near future, dominated by China and determined by shipping routes across the iceless Arctic.

China’s ‘ten-dash line’

While there’s no indication that this map represents the Chinese government’s “official” worldview, it is no secret that China has a thing with maps – and more specifically, the country’s representation on them.

In China, the country’s current economic success is seen as a redress of the unequal treatment meted out by western superpowers in the 19th century. China’s world dominance is a return to a more natural state of world affairs, many feel. Cartographic rectifications are a symbolically significant corollary of that sentiment.

Fines are regularly imposed on companies – domestic and foreign – that fail to represent China to the fullest extent of its external borders, disputed though they may be by others (e.g. India, Taiwan and any of the countries with claims overlapping China’s in the South China Sea). But the People’s Republic’s cartographic obsession doesn’t end at China’s territory itself. It also includes the country’s position on the world map.

The Kingdom at the Middle of the World

China’s name for itself is Zhōngguó, which means ‘Central State’ or ‘Middle Kingdom’, reflecting its ancient self-image as the civilized center (Huá) of the world, with wild tribes (Yí) at the edge. That view is not unique to China. Vietnam, for example, at certain times also styled itself as the “central state” (Trung Quóc) – considering the Chinese in turn as the uncouth outsiders.

It may be surprising to recall, but Europeans themselves once considered their own continent a relative backwater, viewing Jerusalem as the true center of the world. That changed with the Age of Discovery, which placed Europe at the center of an ever-expanding world. Maps reflected that worldview, and largely continue to do so. That’s why today’s standard world map still has Europe at its center – with China off toward the periphery on the map’s right-hand side.

The most notable feature of the very first major modern world map produced in China, the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (1602), is that it places China firmly at the center of the world. Produced for the Chinese emperor by Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, it was the first map ever to combine that perspective with modern western knowledge: it was the first Chinese map to show the Americas, for instance.

That representation may not have taken off elsewhere, but it will be instantly recognizable to Chinese students, as it’s the standard format for world maps in China’s schools today.

America on its head

For those used to “classic” Eurocentric world maps, Europe’s marginalization may come across as a bit of an upset. America’s new position on the horizontal Chinese world map is less jarring: It merely moves from the left- to the right-hand side of the picture. But then there’s this vertical world map, which deals a similar blow to the American land mass: divided in two and pushed to the upper and lower edges of the map.

Unfamiliar? Sure. Shocking? Perhaps. Wrong? Not really. First off, no world map is totally right, since it’s mathematically impossible to transfer the surface of a three-dimensional object onto a flat surface without some distortion. And since the world is a globe, where you center that map is a matter of purely subjective choice.

Those choices have historical reasons. Mercator’s map was not specifically designed to put an inflated Europe at the center of the world. That was just a side effect; its main purpose was to aid shipping: Straight lines on the map correspond to straight lines sailed on the seas.

The vertical world map, showing the relative proximity of China (and the rest of Asia) to Europe and (even the East Coast of) North America, has a similarly maritime raison d’être, or it will have by mid-century. Experts project that by 2050 (if not sooner), the Arctic will be sufficiently ice-free to enable the so-called Transpolar Passage, i.e. shipping straight across the North Pole.

That would shave more than three weeks off a traditional sea voyage between Europe and Asia, via the Suez Canal – and even be significantly faster than other northern alternatives like the Northwest Passage (via Canada) or the Northern Sea Route (hugging the Siberian coast). Since ships would not need to go through locks or pass over shallow waters, it would also remove current restrictions on tonnage per ship.

The only country seriously preparing for such a future: China. None of the other Arctic powers is giving the Transpolar route any strategic thought. On the other hand, China’s Arctic Policy document, released in January 2018, already matter-of-factly refers to the Transpolar route as the ‘Central Passage’ – one of several ‘Polar Silk Roads’ that China seems to want to develop. And they already have the world map to go with it.

Strange Maps #984

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.