“Flight shame”: Not even Europe’s famous rail network can replace airplanes

- If you can take a train instead of a plane, you should do it, say “flight shamers.” It’s better for the planet.

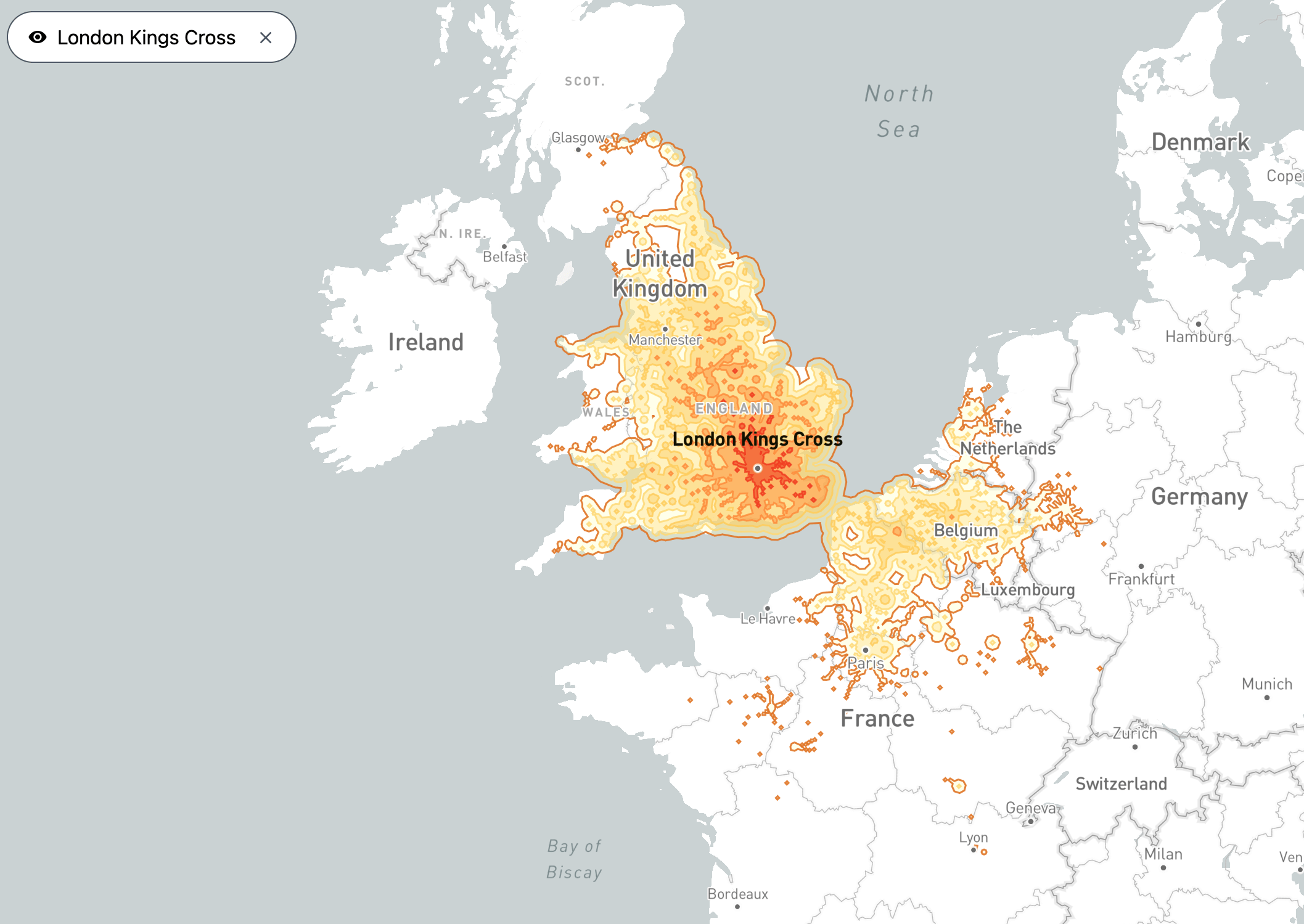

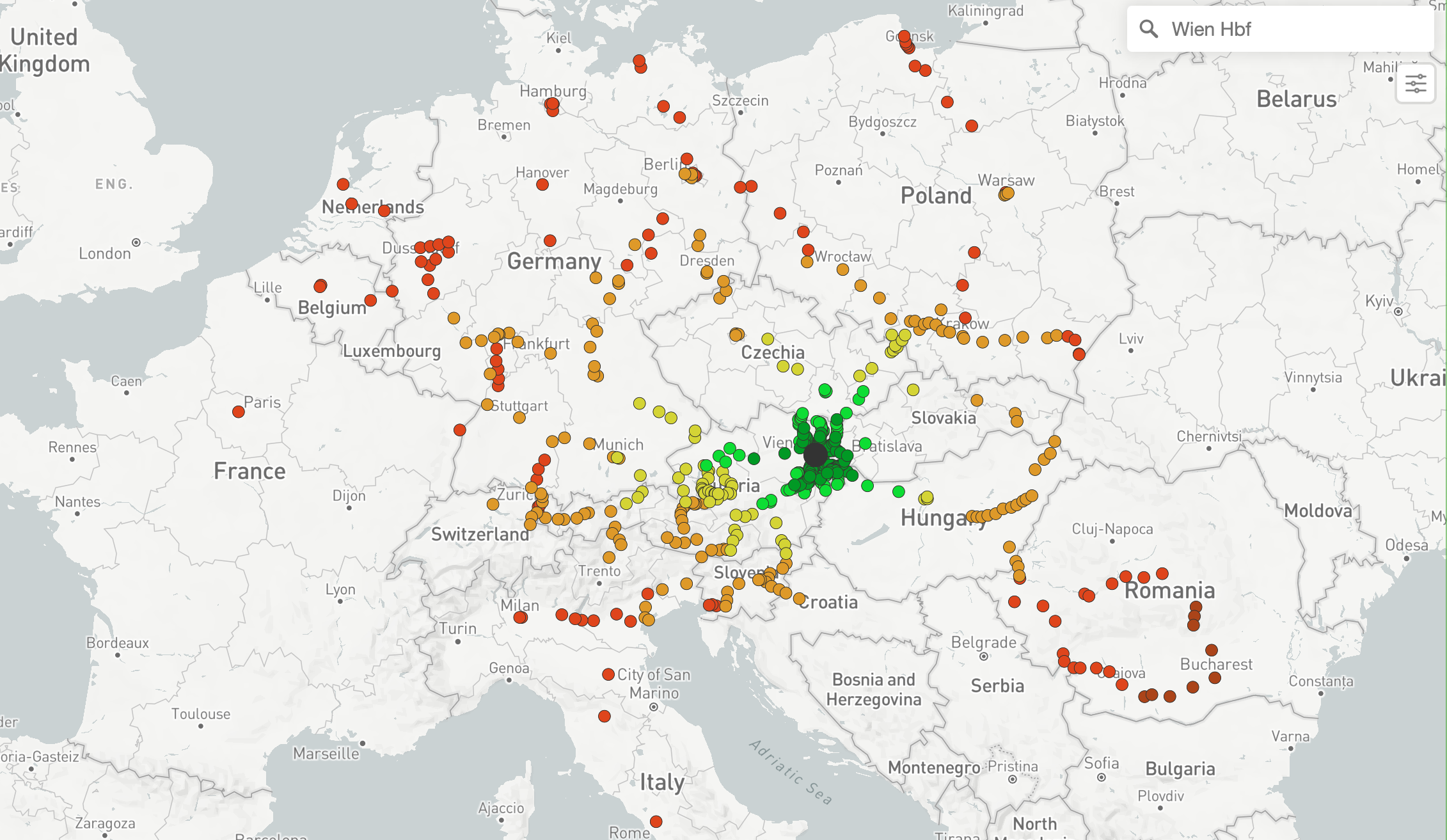

- But is it doable? These isochrone maps show at a glance how far five hours on a train will take you.

- In core European countries, trains make more sense. On the periphery, it’s a different matter.

You could just call it “flight shame,” but the Swedish word flygskam — pronounced “fleek scum” — is a lot more fun. It was popularized a few years ago by Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg.

The word describes the feeling of shame she believes that people should feel when considering a plane ride for which a greener alternative exists. Why? Because commercial flights are responsible for 2.5% of the world’s carbon emissions. Thunberg herself took flygskam to extremes when she sailed across the Atlantic in 2019 to visit the U.S.

“Flight shame” vs. “train bragging”

That’s an option most transatlantic travelers are unwilling or unable to consider. More generally, however, “flight shame” is understood to apply to those short- and medium-distance flights for which practical alternatives are available, typically by rail.

By choosing train over plane, you not only minimize your carbon footprint, you also maximize your sense of environmental altruism. If you choose to broadcast your good deeds to the world, the Swedes have a word for that as well: tågskryta, or “train bragging.”

Both terms are more than buzzwords. The example set by Thunberg and others did change travel habits, certainly in Sweden itself. At the start of 2018, 20% of Swedes said they would choose trains over flights whenever possible. By mid-2019, that figure had risen to 37%. In that year, domestic air travel in Sweden declined by 15%, while the Swedish national rail company reported a 12% rise in business travel.

When are trains a good alternative?

But “flight shame” is not limited to Sweden, nor to individual activists. Across Europe, a substantial number of public and private companies have banned short-haul flights for their staff and are discouraging long-haul ones. It remains to be seen whether, with post-pandemic air traffic well on its way to return to pre-2019 volumes, flygskam can make a long-term dent in flying habits.

A critical element in the train-versus-plane consideration is whether your rail alternatives are any good. Yes, trains can be a convenient means to travel from city center to city center, especially in countries and regions where the network is dense and the service is fast. But if you’re going a bit off the beaten track, be prepared to spend a lot more time travelling than you would by plane or car.

You know what would really help? A map that shows just how fast and far you can travel by train from your starting point, so you can actually see whether rail is a viable alternative to flight. And that’s exactly what these maps do.

The maps come from a site called Chronotrains, which does one thing, and one thing only. It answers the question: How far can you go by train in five hours?

Isochrone maps to the rescue

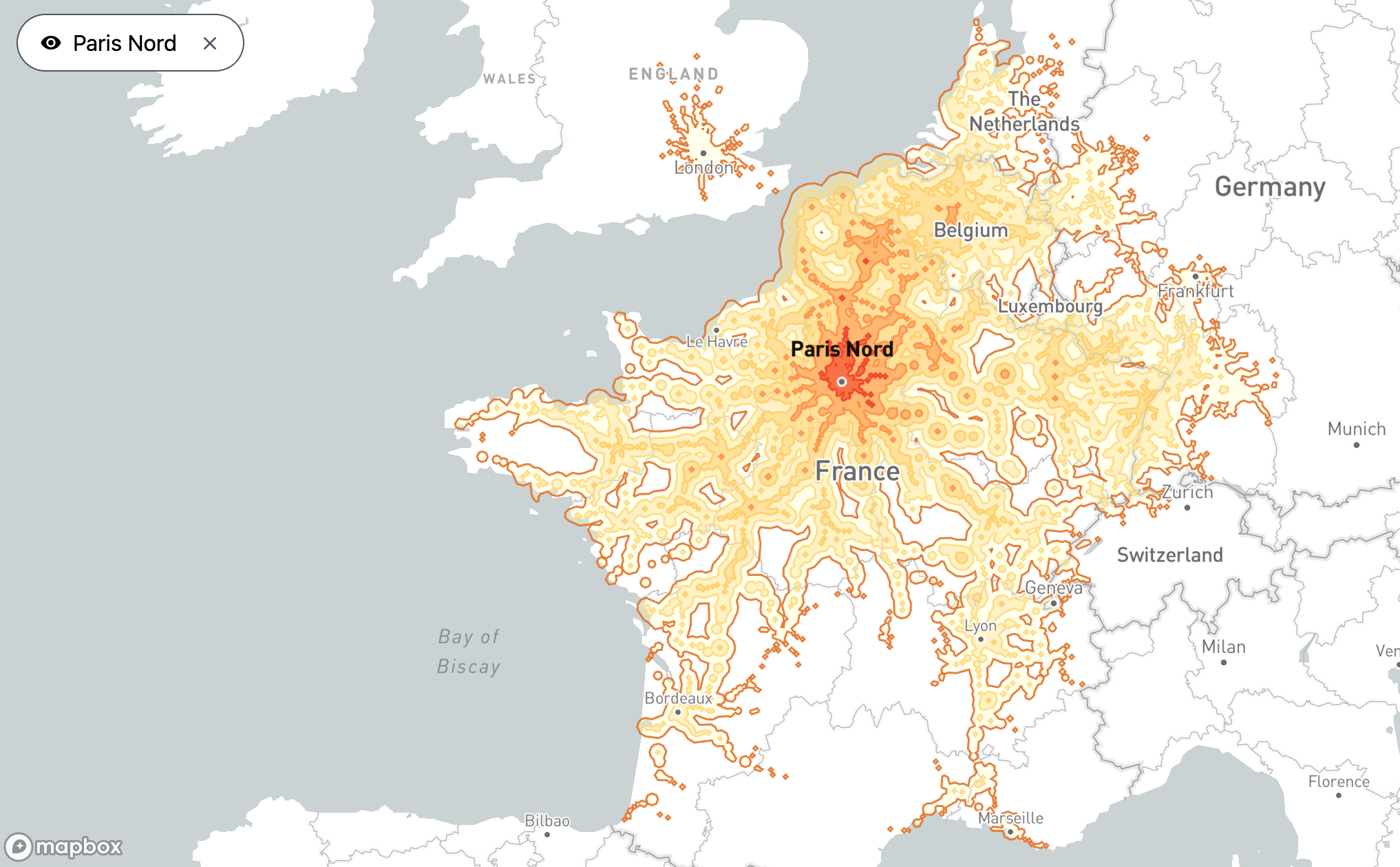

For any train station in Europe (or at least in those countries highlighted in white), it shows you which destinations you can reach in five hours or less. The result each time is a blob of varying size and radiating color. Red, the hottest shade, is reserved for stations that can be reached within the hour, while orange means two hours, and a trio of increasingly pale shades of yellow add another hour each.

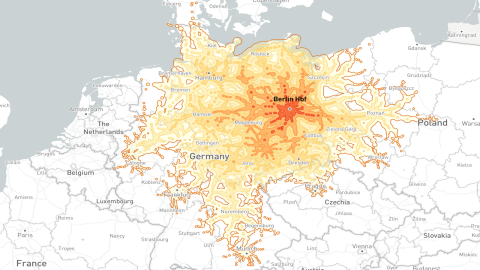

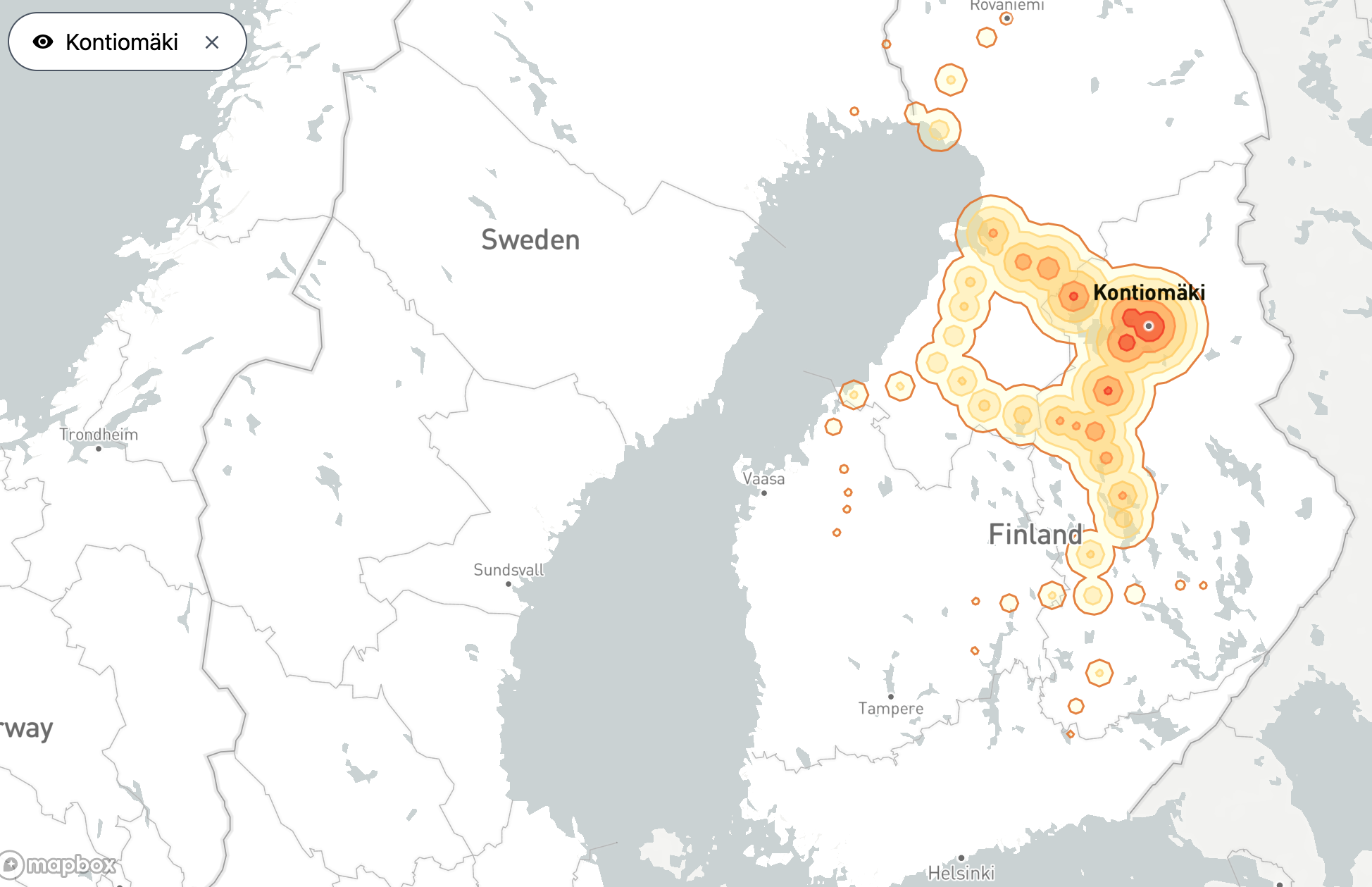

Maps of this kind are called isochrones because they show areas that can be reached in equal time (iso is Greek for “same”; chronos means “time”). As you mouse over train stations ranging from the legendary (Paris Gare du Nord) to the obscure (say, Kontiomäki, in the vast and thinly populated middle of Finland), your armchair travels reveal just how out of whack train travel is across the continent.

From Kontiomäki, five hours on the train barely gets you across the Swedish border (into Kalix Station, in the very north of the country), and not even to the Finnish capital, Helsinki.

Start from the Gare du Nord in Paris however, and you can make it past London all the way up to Peterborough in England, or to Den Helder at the northern tip of Holland, beyond Amsterdam. In Germany, you can get to the major cities of Cologne, Frankfurt, and Stuttgart. Or if you head south, you could be in the resort town of Biarritz, on France’s southern Atlantic coast, within five hours; or in Marseille and beyond, on the Mediterranean.

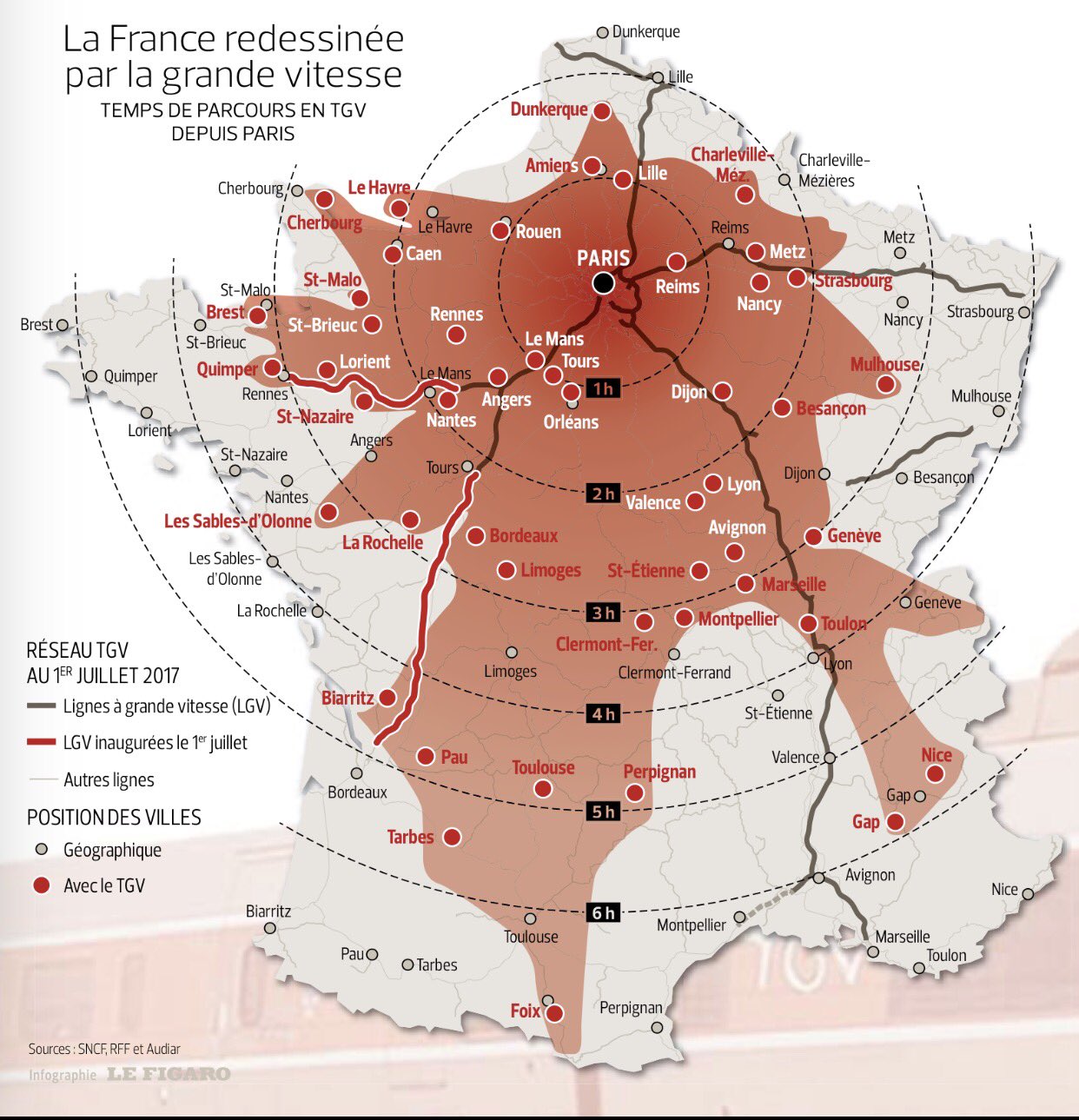

France, the pioneer of high-speed trains

It’s not just that Finland is larger and emptier than France. The French rail network is denser than the Finnish one, but most important of all: faster. France is a pioneer in Europe of high-speed trains, or TGVs (Trains à Grande Vitesse). Finland isn’t. Marseille is about 500 miles (800 km) from Paris. That same distance south of Kontiomäki puts you somewhere between St. Petersburg and Moscow — a lot further than a Finnish train will take you in five hours.

It is however far from the case that all stations in the more populated parts of Europe are isochronic equals. It helps if you leave from a central station. Take for instance Berlin Hauptbahnhof. The five-hour blob centered on Berlin’s main train station covers most of northern Germany, and its limits go as far as Kolding (Denmark) in the north, Kutno (Poland) in the east, Munich in the south, and Aachen in the west.

But leave from the smaller station of Neubrandenburg, north of Berlin, and your isochronic blob doesn’t even cover the whole of former East Germany. There is some minor leakage into Poland. But despite the fact that you can get to Hamburg, Bremen, and Hannover within five hours, that’s about as far as you get into former West Germany, apart from one particularly fast train that gets you south to Nuremberg.

Borders are barriers, but not always

As you continue your game of station-to-station, it becomes obvious that national borders still serve as barriers: Train service often thins out as you cross over from one country to the next. However, there is also evidence to the contrary. Take London’s King’s Cross station. Thanks to the Eurostar that crosses into mainland Europe via the Channel Tunnel, you can get to almost any place in Belgium and as far south as Lyon in France; but you won’t make it much further north in Britain itself than the middle of Scotland (granted, that does include that country’s two major cities, Glasgow and Edinburgh).

Chronotrains was developed over a week this past summer by Benjamin Tran Dinh, a Paris-based software developer. He was inspired by Direkt Bahn Guru, a German site that does something similar: It shows all the cities that are accessible from any given European station without changing trains.

Train exchanges are included on Tran Dinh’s map, but to facilitate calculations, it is assumed each takes no more than 20 minutes. In reality, many are quite a bit longer. The five-hour maximum on these maps is therefore on the optimistic side.

Differences in transport infrastructure policy

The spark for Chronotrains, Tran Dinh told Le Figaro, were “anamorphic maps of France, showing how the TGV has shrunk travel times from Paris.” (An anamorphic map, a.k.a. “cartogram,” distorts geographic size in proportion to a certain dataset, such as population, GDP, or travel time — in the latter case, also serving as an isochronic map).

It turned out that the database behind Direkt Bahn Guru, provided by Germany’s national rail operator Deutsche Bahn, was Europe-wide and open-source. Tran Dinh built Chronotrains “more out of a passion for cartography than an interest in trains.” But building the site and playing with the data did give the developer a better appreciation for the specifics of rail travel speeds:

“As you browse the map, you see the disparities in access to rail transport between cities, and you see how privileged those with high-speed connections are. The map tells stories about the differences in transport infrastructure policy from one region to the next.”

And on top of that, it will help you choose between flygskam and tågskryta.

Strange Maps #1177

Check out Chronotrains, designed by Benjamin Tran Dinh, and its inspiration, Direkt Bahn Guru.

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.