Five Hawks Down: watch the tragic migration of six Californian raptors

Image: @TrackingTalons / Ruland Kolen

- Watch these six dots move across the map and be moved yourself: this is a story about coming of age, discovery, hardship, death and survival.

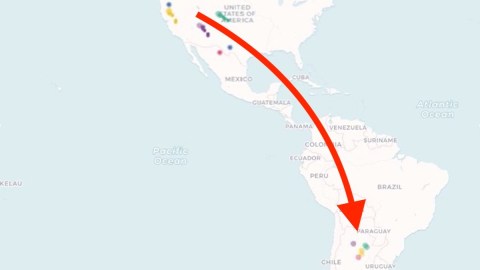

- Each dot is a tag attached to the talon of a Swainson’s Hawk. We follow them on their very first migration, from northern California all the way down to Argentina.

- After one year, only one is still alive.

Discovered: destination Argentina

The Buteo swainsoni is a slim, graceful hawk that nests from the Great Plains all the way to northern California.

It feeds mainly on insects, but will also prey on rodents, snakes and birds when raising their young. These learn to fly about 45 days after hatching but may remain with their parents until fall migration, building up flying skills and fat reserves.

A common sight in summer over the Prairies and the West, Swainson’s hawks disappear every autumn. While it was assumed they migrated south, it was long unclear precisely where they went.

A group of researchers that has been studying raptors in northern California for over 40 years has now established exactly where young Swainson’s hawks go in winter. The story of their odyssey, summarized in a 30-second clip (scroll down), is both amazing and shocking.

Harnessing the hawks

The team harnessed six Swainson’s hawks in July, as they were six weeks old and just learning to fly. The clip covers 14 months, until next August – so basically, the first year of flight.

Each harness contains a solar-powered tracker and weighs 20 grams, which represents just 3% of the bird’s body weight. To minimize the burden, only females were harnessed: as with most raptors, Swainson’s hawk females generally are bigger than males.

The first shock occurs just one month (or about 2.4 seconds) from the start of the clip: the first dot disappears. The first casualty. A fledgling no more than two months old, who never made it further than 20 miles from its nest.

By that time, the remaining five are well on their way, clustering around the U.S.-Mexico border in Texas. Swainson’s hawks usually travel at around 40 mph (65 km/h) but can almost double that speed when they’re stooping (i.e. dive down, especially when attacking prey).

‘Migration unrest’

There’s a strong genetic component to migration. As usual, the Germans have nice single word to summarize this complex concept: Zugunruhe (‘tsook-n-roowa’), literally: ‘migration unrest’ (1). It denotes the seasonal urge of migratory animals – especially birds – to get on their way. Zugunruhe exhibits especially as restless behavior around nightfall. The number of nights on which it occurs is apparently higher if the distance to be traveled is longer.

The birds may have the urge to go south, but genetics doesn’t tell them the exact route. They have to find that out by trial and error. Hence the circling about by the specimens in this clip: they’re getting a sense of where to find food and which direction to go. Their migratory paths will be refined by experience – if they’re lucky enough to survive that long.

Each bird flies solo: their paths often strongly diverge, and if they seem to meet up occasionally, that’s just an illusion: even when the dots are close together, they can still be dozens if not hundreds of miles apart.

Panama snack stop

They generally follow the same route as it is the path of least resistance: follow mountain ranges, stay over land. Like most raptors, Swainson’s hawks migration paths are land-based: not just so they can roost at night, but mainly to benefit from the thermals and updrafts to keep them aloft. That reduces the need to flap wings, and thus their energy spend – even though the trip will take longer that way.

As this clip demonstrates, the land-migration imperative means the Central American isthmus is a hotspot for bird migration. Indeed, Panama and Costa Rica are favorite destinations for bird watchers, when the season’s right. A bit to the north, Veracruz in Mexico is another bird migration hotspot.

It’s thought most hawks don’t eat at all on migration. This clip shows an exception to that rule: on the way back, one bird takes an extended stopover of a couple of weeks in Panama, probably spending its time there foraging for food.

So, when they finally arrive in northern Argentina, after 6 to 8 weeks’ migration, the hawks are pretty famished. Until a few decades ago, they fed on locusts. For their own reasons, local farmers have been getting rid of those. The hawks now concentrate on grasshoppers, and basically anything else that’s edible.

For first-time visitors, finding what they need is not easy. Three of the five dots go dark. These birds probably died from starvation. But two birds thrive: they roam the region until winter rears its head in South America, and it’s time to head back north again, where summer is getting under way.

Both dots make it back across the border, but unfortunately, right at the end of the clip, one of the surviving two birds expires.

Harsh, but not unusual

While a one-in-six survival rate may seem alarmingly harsh, it’s not that unusual. First-year mortality for Swainson’s Hawks is between 50% and 80%. Disease, starvation, predators and power lines – to name just a few common causes of death – take out a big number.

Only 10% to 15% of the young ‘uns make it past their third or fourth year into adulthood, but from then on, annual survival rates are much better: around 90%. Adult Swainson’s Hawks can expect to live into their low teens. There’s one documented example of a female Swainson’s Hawk in the wild who was at least 27 years old (and still nesting!)

The Californian population of Swainson’s Hawks plummeted by about 90% at the end of last century but is now again increasing well. The monitoring project that produced this clip has been going for about four decades but is seeing its funding dry up. Check them out and consider supporting them (see details below).

Migration trajectory of B95, the ‘Moonbird’.

Not all migrating birds shun the ocean. Here’s an incredible map of an incredible migration path that’s even longer than that of the Swainson’s hawks.

In February 1995, a red knot (Calidris canutus rufa) in Tierra del Fuego (southern Argentina) was banded with the tag B95. That particular bird, likely born in 1993, was recaptured at least three times and resighted as recently as May 2014, in the Canadian Arctic.

B95 is more commonly known as ‘Moonbird’, because the length of its annual migration (app. 20,000 miles; 32,000 km) combined with its extreme longevity (if still alive, it’s 25-26 years old now) means its total lifetime flight exceeds the distance from the Earth to the Moon.

As many other shorebirds do, the red knot takes the Atlantic Flyway hugging the coastline and crossing to South America via the ocean.

B95 has become the poster bird of conservationists in both North and South America. A book titled Moonbird: A Year on the Wind with the Great Survivor B95 (2012) received numerous awards, B95 has a statue in Mispillion Harbor on Delaware Bay and the City of Rio Grande on Tierra del Fuego has proclaimed B95 its natural ambassador.

Perhaps one day the nameless Swainson’s Hawks in this clip, fallen in service of their ancestral instincts – against the odds of human increasing interference – will receive a similar honor.

Migration clip found here at the DataIsBeautiful subreddit. Read through the comments to learn a lot more about Swainson’s Hawks, and raptors in general.

Check out the California raptor tracking programme ‘Tracking Talons’ on Twitter at @TrackingTalons, on their Facebook page, and on their website.

Strange Maps #965

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) ‘Zug’ is a wonderfully polyvalent German word. It can mean: a train, a chess move, a characteristic, a stroke, a draft (of a plan), a gulp (of air), a drag (from a cigarette), a swig (from a bottle), and more.