The past is a different country. And not just in the poetic sense. In the early 19th century, the United States was much smaller than it is today. But by the end of that century, the U.S. had consolidated into an empire both in the continental sense as well as the colonial one: not only did it stretch across the entirety of North America, from sea to shining sea, it also had acquired significant amounts of territory and influence beyond those shores.

Decidedly non-progressive

America’s imperial girth and radiance may seem like faits accomplis today, but they were vehemently contested by the domestic press of the time. At the very tail of the century, this opposition led to a curious cartographic phenomenon which, despite its anti-imperialist origins, we today recognize as a decidedly non-progressive practice: the fat-shaming of Uncle Sam.

Uncle Sam is the personification of the United States (the country and, often specifically, its government), with which he shares his initials. His exact origins are unknown, although an apocryphal reference is often made to Samuel Wilson, a meat packer from Troy, NY and supplier of American troops during the War of 1812. Authenticity concerns aside, ever since 1989, the U.S. has had an annual Uncle Sam Day on September 13th, Wilson’s birthday.

However, Uncle Sam is also the continuation of Brother Jonathan, who personified the typical New England Yankee and has his origins in the 17th-century English Civil War (where the term was used by the Royalists to mock the Puritans). Sam certainly borrowed Jonathan’s striped pants, stove-pipe hat, and lanky figure. The thinness and old-fashioned appearance of both Jonathan and Sam (who were interchangeable by the mid-19th century) were meant to symbolize a kind of restless thriftiness, a supposedly national trait of the Yankee — and by extension, the American nation.

A lightning rod for criticism

Around the time of the Civil War, Sam had largely supplanted Jonathan as a national figure. As a sort of shorthand of the U.S., Uncle Sam was a favorite of cartoonists in the 19th and 20th centuries. (He seems to have gone a bit out of fashion in the 21st.) Especially during the World Wars, he was used as a symbol of national resilience and an important ingredient of patriotic propaganda. Inversely, he was also easily adopted as a lightning rod for criticism of the U.S. and its international policies.

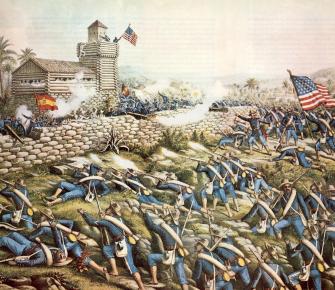

In various cartoons of the 19th century’s last decade, Uncle Sam — recognizable by his goatee and tricolored clothes — is depicted as increasingly fat and mocked for it. His embonpoint is understood to be a symbol of geopolitical gluttony, making him — that is, the United States itself — appear both avaricious and ridiculous on the world stage. This was the build-up toward the Spanish-American war of 1898, from which the U.S. would emerge victorious and in possession of much of Spain’s remaining overseas empire, consisting of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and other smaller island territories.

This can be seen as America’s Julius Caesar moment — when it, like Rome before it, changed from a republic into an empire. It was certainly recognized (and feared) as such in those days.

Trying to swallow Cuba whole

On August 10, 1895, the satirical magazine Judge published a cartoon by Victor Gillam on its front page that showed a modified map of North America, enlisting the continent’s geography to make a shockingly visceral, anti-imperialist point.

Cuba is shown as a small fish, attempting to swim away from the maw of Uncle Sam, who coincides with North America itself. Mexico is his lower jaw, Central America his goatee, Florida his nose, Washington, DC his all-seeing eye, and Canada his hat.

The map is entitled The Trouble in Cuba. The trouble seems to be that Cuba refuses to be swallowed by Uncle Sam, who says, “I’ve had my eye on that morsel for a long time; guess I’ll have to take it in!”

An expansionist menu

In this cartoon, Uncle Sam, identified with President McKinley, is presented as a glutton and his detractors as too slow to stop him. In 1898, the United States had won the Spanish-American War, laying claim to Puerto Rico and the Philippines among other spoils of the now defunct Spanish empire. In the same year, the U.S. had also acquired Hawaii as a territory.

Many in Congress worried that McKinley’s policy of continued expansion would lead to imperialism. Bursting through the door to prevent Uncle Sam from gobbling up a load of overseas territories are Representative William Jennings Bryan and Senator George Frisbie Hoar. They are too late; the plates are empty. On the ground is an Expansion Menu, listing what just has been devoured: Hawaiian Soup, Portorican Rice (?), Philippine Pudding.

Cracks in the pond

This centerfold cartoon from the New York Herald of November 26, 1898 shows the comically rotund figures of Uncle Sam and President McKinley, skating across a wintery landscape on a body of water labelled Expansion Pond. A rather joyless figure in a deerstalker hat, perhaps newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer, known for his anti-expansionist stance, does not want to join in the fun. “I will not skate on your pond,” he avers.

Big, bigger, best?

In 1899, Judge published another cartoon by Victor Gillam, entitled A Lesson for Anti-Expansionists. Showing the growth of Uncle Sam over the various stages of his life, that lesson is how the U.S. “has been an expansionist first, last, and all the time.”

- On the left, the U.S. starts out as an infant (1783, 13 states).

- The second figure is a strapping young lad confidently leaning on a frontiersman’s axe (1803, Louisiana Purchase).

- The third figure is a stern-looking, musket-holding soldier (1819, Florida ceded by Spain).

- The fourth figure is a supremely confident-looking gentleman, newly goateed and top-hatted (1861, having recently annexed Texas).

- Fifth is an older gentleman, slightly roguish and rotund (1898, annexed Hawaii).

- In just one year, Uncle Sam has gone from merely full-figured to morbidly obese but with a confident smirk on his face and a ship under his arm, as a symbol of the naval prowess that earned him various colonies (Cuba, Philippines, Porto Rico [sic] in 1899).

The final figure is pondering the many hands outstretched toward him, labelled as Russia, China, Germany, England, and other world powers. “And now all the nations are anxious to be on friendly terms with Uncle Sam,” the caption reads. Unlike Gillam’s earlier cartoon, this one can be construed as ambiguous: is this a critique of expansionism or an acknowledgement of the influence that expansion has brought with it?

Expand and explode

Gillam may have been inspired by a cartoon published earlier that year in Life magazine, which depicts a similarly inflating Uncle Sam, but with a more dramatic finale.

- Uncle Sam starts out as his full-grown, slim-figured self in 1776.

- The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 seems to subtract rather than to add to his joy.

- The annexations of Alaska and Texas only add to his discomfort.

- Discomfort turns to distemper in 1898, with the takeover of the defunct Spanish empire in the Pacific and Caribbean.

- Growing ever bigger and more agitated over the course of these additions, can it be far off before Uncle Sam simply explodes?

Intervention at the tailor shop

This cartoon from 1900 shows then-President William McKinley as a tailor, sizing up an enormous Uncle Sam. The striped pants list Sam’s recent acquisitions, from Louisiana and California to Hawaii and Porto Rico.

McKinley is getting ready to cut Uncle Sam a new suit from cloth labelled “enlightened foreign policy – rational expansion.” But three stern-looking gentlemen have entered McKinley’s tailor shop and are keen for another course of action. They want to administer a medicine called “anti-expansionist policy.”

The most prominent of the three would have been recognized by contemporaries as publishing magnate Joseph Pulitzer, campaigner against imperial expansion. He says, “Here, take a dose of this anti-fat and get thin again!” To which Uncle Sam replies, “No, Sonny! I never did take any of that stuff, and I’m too old to begin!”

And… thin again

Uncle Sam and other national personifications have several advantages over real people — one of those is that they can change body type to fit the situation.

Despite years of cartoons showing Uncle Sam as getting too big for his britches, in this illustration from 1900 he reverts to type, becoming rail-thin again. The reason: to contrast with that other national archetype, John Bull, representing the British Empire, which was then at its height. How do you personify a globe-spanning empire? By fattening up the figure in question.

Without knowing anything about the content of The Fable of John Bull and Uncle Sam, it is safe to say, judging from the stance of both figures alone, that it will show the former as unworthy of his leading role in the world with the latter more capable and willing to assume that role.

Most maps were taken from this article on Carto-Caricatures, a fascinating blog about the intersection between cartography and caricature.

Strange Maps #1097

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.