What’s another name for France? The French have several options. One is la France métropolitaine, or simply la Métropole, a reference to France-in-Europe being the hub of a global empire — although these days that consists of little more than a few far-flung islands. Another is l’Hexagone, for the French mainland’s vaguely six-sided shape.*

That much-used geometrical figure of speech contains a more obscure one, ominously named le Diagonal du vide, or “the Empty Diagonal.” It echoes the name of Arabia’s Empty Quarter (in Arabic: Rub’ al Khali), that corner of the Arabian Peninsula so devoid of everything but sand that it was used as a stand-in for the desert planet of Arrakis in the recent Dune movie.

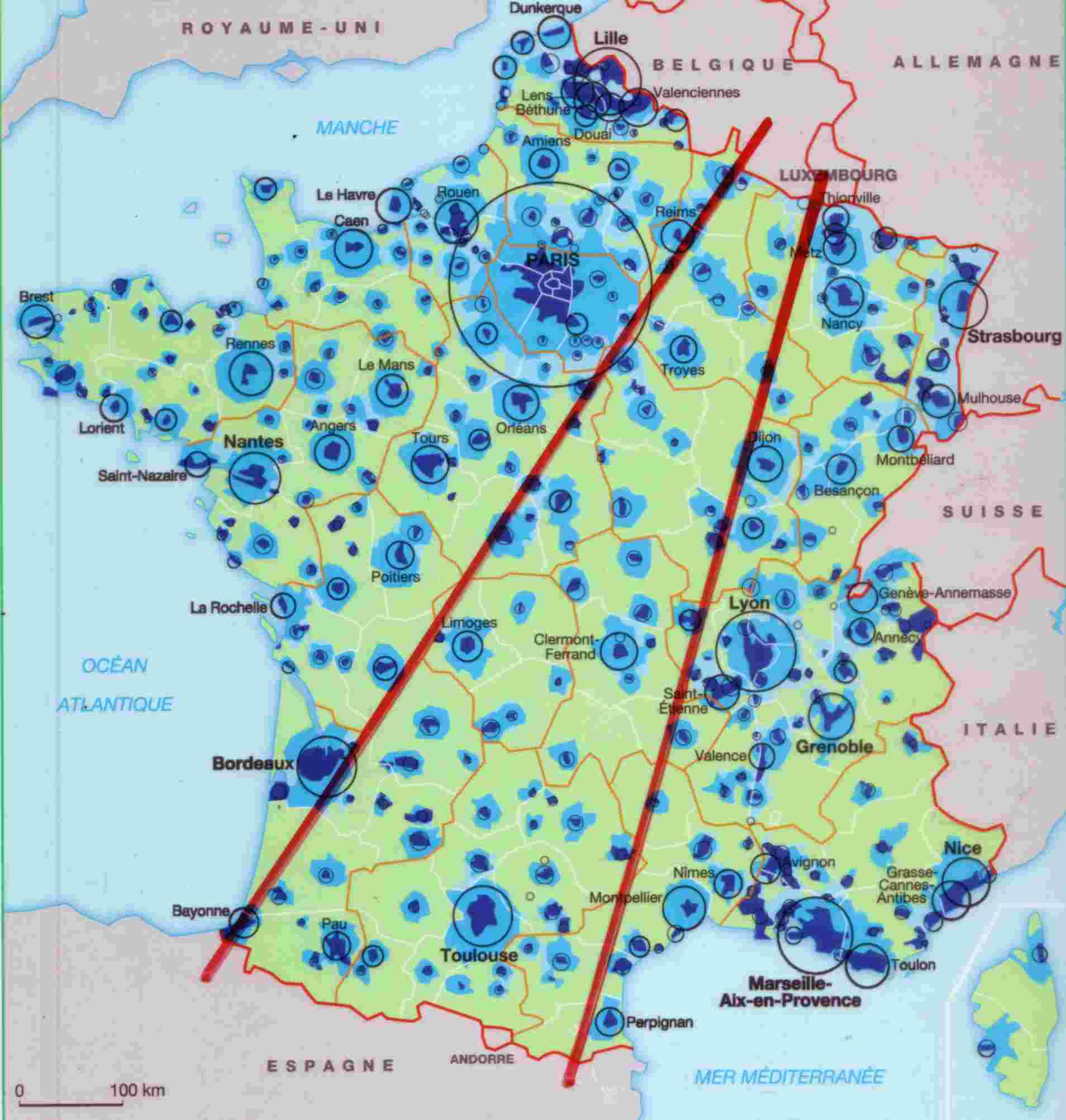

There are no sand dunes (or sand worms) in France’s Empty Diagonal, but it is so devoid of people that it nevertheless invites comparisons to an actual desert. The Diagonal cuts right across France, from the Meuse department, on the Belgian border in the northeast, to the Landes department in the southwest, near the Spanish border. Population density in the Diagonal is generally around or below 30 inhabitants per square km, much lower than the French average of 119 people/sq km. (By comparison, Paris has 20,386 inhabitants/sq km.)

Historically speaking, that demographic imbalance is of fairly recent vintage. France’s countryside started emptying out around the middle of the 19th century, prompted by industrialization, urbanization, and low fertility rates. Those phenomena hit France earlier than most other European countries. Why? In a word: Paris. For centuries, the city on the Seine has attracted talent, capital, and people like no other European capital, much to the detriment of the rest of France.

That at least is the gist of Paris et le désert français (1947), the seminal work by geographer Jean-François Gravier. He traces the city’s gravitational pull to the court of Louis XIV. To keep both friends and enemies close, the Sun King consciously drew in ambitious elites from all over the country to his sumptuous residence at Versailles, just outside Paris.

They came like bees to honey. And they kept coming, even after the French Revolution got rid of the monarchy. As radical acolytes of the Enlightenment, the early revolutionaries were wary of the traditionalism of “la province”, much preferring the hustle and bustle of Paris, the cauldron of modernity. From Napoleon onward, Paris became the essential showcase of France’s power and prestige.

Political centralism led to economic concentration, and Paris became one of the world’s great destinations of migration, albeit initially mostly from within France itself. In 1920, just 39% of its inhabitants were native to the city. Half were immigrants from the French countryside, with another 10% coming from outside France’s borders. (See Strange Maps #360).

Gravier was not a fan. Since 1850, he said, “the urban agglomeration of Paris has behaved not as a metropolis invigorating its hinterland, but as a monopolist, consuming the essence of the nation.” Because of the capital’s much lower fertility rate, Paris was “an urban monster, depriving France each year of three times as much human capital as alcoholism.”

Even back then, the geographer displayed a cultural pessimism that would fit right in with today’s prophets of doom: “As Poles, Italians, and Spaniards come to replace the children that the French themselves didn’t want to have, some will inevitably be reminded of the Late Roman Empire, slowly being invaded by the Barbarians.”

Tainted by participation in right-wing fringe organizations before WWII and collaboration during the war, Gravier was no stranger to controversy. Yet the essence of his “ruralist” message resonated with public opinion in post-war France and informed several attempts in the second half of the 20th century to decentralize the French state and reverse the effect of the capital’s fatal attraction on the rest of the country.

It is fair to say that those attempts have not quite succeeded. In fact, the term Diagonal du vide gained popularity as recently as the 1990s, as a more precise successor to Gravier’s “French desert.” Despite the fact that the Empty Diagonal does contain some centers with growth potential, notably cities such as Toulouse or Clermont-Ferrand, the general trend still is one of population decline. Some areas have more deaths than births, others more people leaving than arriving. And in some, it’s both.

Formerly buzzing with industry, entire regions in northeast France are emptying out. Factory closures over the last half century have reduced industry and opportunity, increased unemployment and poverty, and fuelled outward migration. And it’s not just northern industry that is on the wane. Over the past 40 years, the number of French people employed in agriculture has declined from 1.6 million to 400,000.

The effect is being felt in towns and villages throughout the Diagonal. In some places, the decline is exponential rather than linear. As populations age and shrink, communities lose services like schools, cafés, bakeries, and shops — which in turn accelerates the decline.

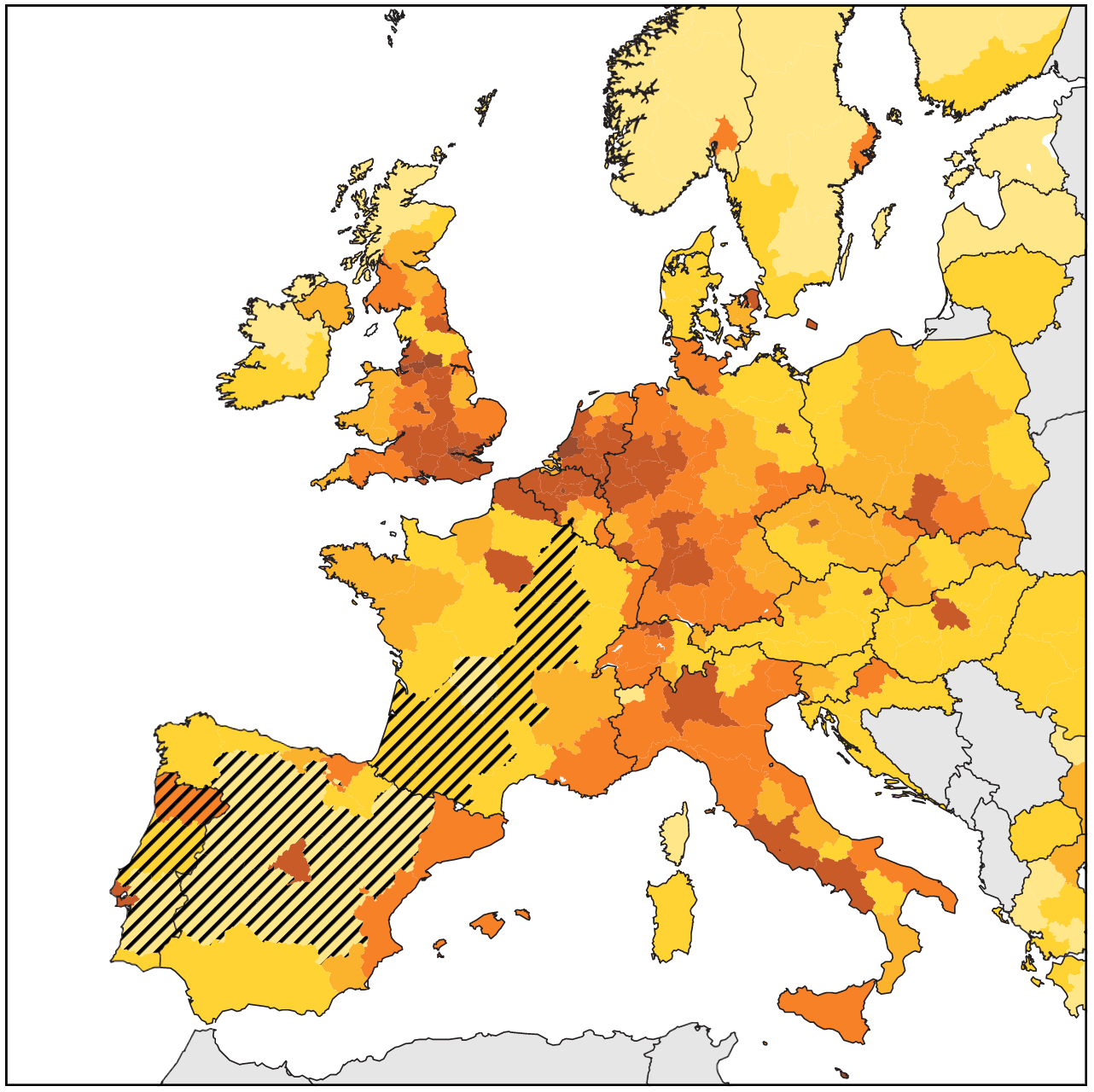

The Empty Diagonal is by no means the only part of rural France suffering from population decline. Other empty(ing) zones outside the Diagonal can be found near the Alps in the southeast and the Pyrenees in the south, among others. Zooming out, the Diagonal is part of a larger area of inland Europe suffering from seemingly interminable decline, extending to much of the Iberian peninsula, including the larger parts of both Spain and Portugal.

However, a label as pithy as the “Empty Diagonal” is so powerfully descriptive that it risks becoming prescriptive. The solution? Give the area another name. Because of the label’s negative connotations, some now prefer to call the desert at the heart of France la Diagonale des faibles densités: the “Low-density Diagonal.” There, problem solved!

Strange Maps #1122

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.

* There are a bunch of other options: La Fille aînée de l’Église (“the Oldest Daughter of the Church”), La Patrie des droits de l’homme (“the Homeland of Human Rights”), La Grande Nation (“the Great Nation,” especially during the Napoleonic Era), Le Pays des Lumières (“the Country of the Enlightenment”), Le Pays des 365 Fromages (“the Country of 365 Cheeses”).