International border changes are like London buses. For ages, nothing happens. And then all of a sudden, a bunch of them arrive at the same time.

And then most proposals end up on the cutting room floor. Case in point: this map of the Confederation of the Danube, a brainchild of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. This giant country would have stretched from France to Ukraine, and would have dominated the map of post-World War II Europe. But in the end, even Churchill himself seems to have gone off the idea.

Over the past two centuries or so, Europe has had three major border-changing moments: the Congress of Vienna (1814-15), reinventing Europe after Napoleon; the Paris Peace Conference (1919-20), filling the gap left by the implosion of the German and Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires; and the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences (1943-45), where the Allies laid the groundwork for Europe’s post-WWII borders.

How to neutralize Germany

One thing at least the Americans, Brits, and Soviets agreed on about Europe after WWII: There would be no repeat of the post-WWI arrangement, which left Germany both angry and powerful enough to attempt a rematch. So Germany had to be neutralized. But how? The easy bit: Germany would have to dismantle its arms industry. Nobody disagreed with that. Much more controversial were two other concepts: eliminating Germany’s entire industrial base and “dismembering” the country.

Dismemberment could mean two different things, and perhaps both at the same time: chopping off bits of territory for its neighbors to annex, and chopping up what remained into smaller German states. At Yalta, the Allies decided that dismemberment would be added to the instrument of unconditional surrender that Germany would soon be forced to sign, and a Committee for the Dismemberment of Germany was set up.

But the Soviets soon started rowing back on the maximalist version of the idea. Stalin saw the threat to cut up Germany into smaller states mainly as a convenient threat to obtain other goals — notably the annexation of eastern Germany by Poland, itself a compensation for the Soviets gobbling up pre-war Polish territory farther east.

The Western Allies also reneged: As the hot war with the Nazis almost seamlessly transmogrified into a Cold War with the Soviets, Britain and the U.S. saw a strong Germany as a bulwark against further Communist encroachment into Europe from the east.

Germany’s accidental division

Of course, post-war Germany did separate into East and West Germany, a situation that was resolved only after the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. However, that separation was an unintended — or at least unplanned — consequence of the nascent Cold War, when the Soviet and Western occupation zones solidified into two opposing satellites of two opposing ideologies: a communist state in the east and a capitalist one in the west.

So, the actual (but accidental) division of Germany post-WWII replaced some of the proposed dismemberment, which was never enacted. No doubt the most famous proposal was the so-called Morgenthau Plan, devised by Henry Morgenthau Jr., U.S. Secretary of the Treasury under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

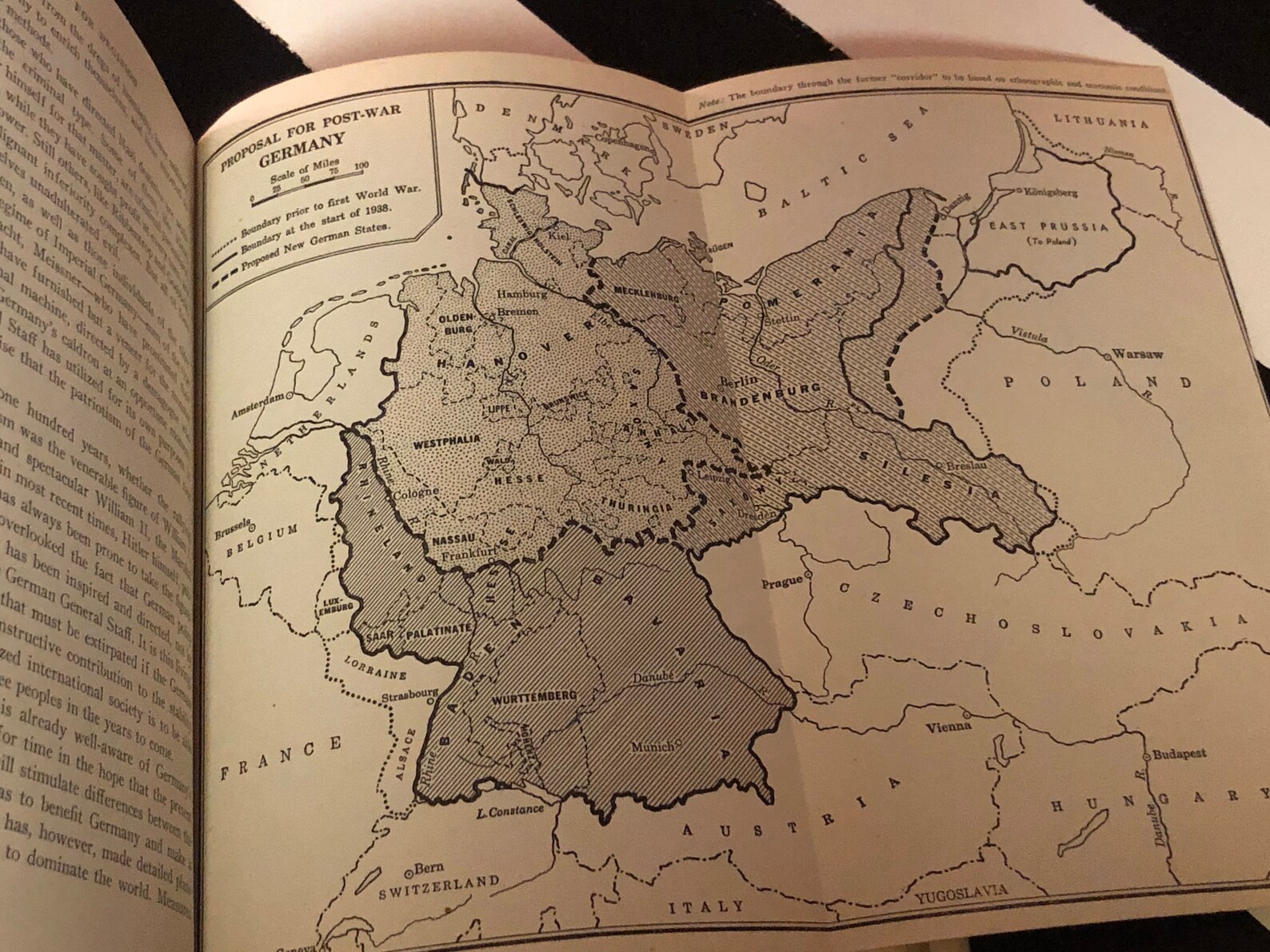

Dismemberment-light: Germany divided into three, as per the Sumner Welles Plan. (Credit: Etsy)

Morgenthau’s plan called for Germany to be thoroughly de-industrialized, so it would become “primarily agricultural and pastoral in character.” Significant parts of the country would be annexed by France and Poland. The remainder would be divided into three separate entities: a North German State, a South German State (in a customs union with Austria, restored to its pre-1938 borders), and an International Zone in the west, governed by an international body that would ensure the area would not re-industrialize.

The plan was published in September 1944 and was immediately seized upon by Nazi propaganda as proof the Allies wanted to “enslave” Germany. Chief propagandist Goebbels made much of the fact that Morgenthau was Jewish.

A plan “worth 30 divisions”

Some Allied commanders blamed the plan for fueling the despair and resistance of the Germans in the last months of the war. It was said to be “worth 30 divisions to the Germans”. After the war, it had some influence on the policy of “industrial disarmament”, which was however abandoned as early as 1947, when it was realized that an economically strong (West) Germany was needed to help (Western) Europe recover from the war.

A more obscure – and more lenient – proposal was formulated by Sumner Welles, FDR’s former Undersecretary of State. While granting East Prussia to Poland, his plan kept the rest of Germany mostly intact, but divided it into three states: in the northwest, east, and south.

The northwestern state would stretch from Hamburg all the way into Saxony (which became part of East Germany in our world). The (mainly Catholic) south would include the (mainly Catholic) Rhineland in the west. And the eastern state would retain most of Pomerania and Silesia. The idea was that three almost equally large, populous, and powerful German states would balance each other out, preventing any one of them to dominate and absorb the other two.

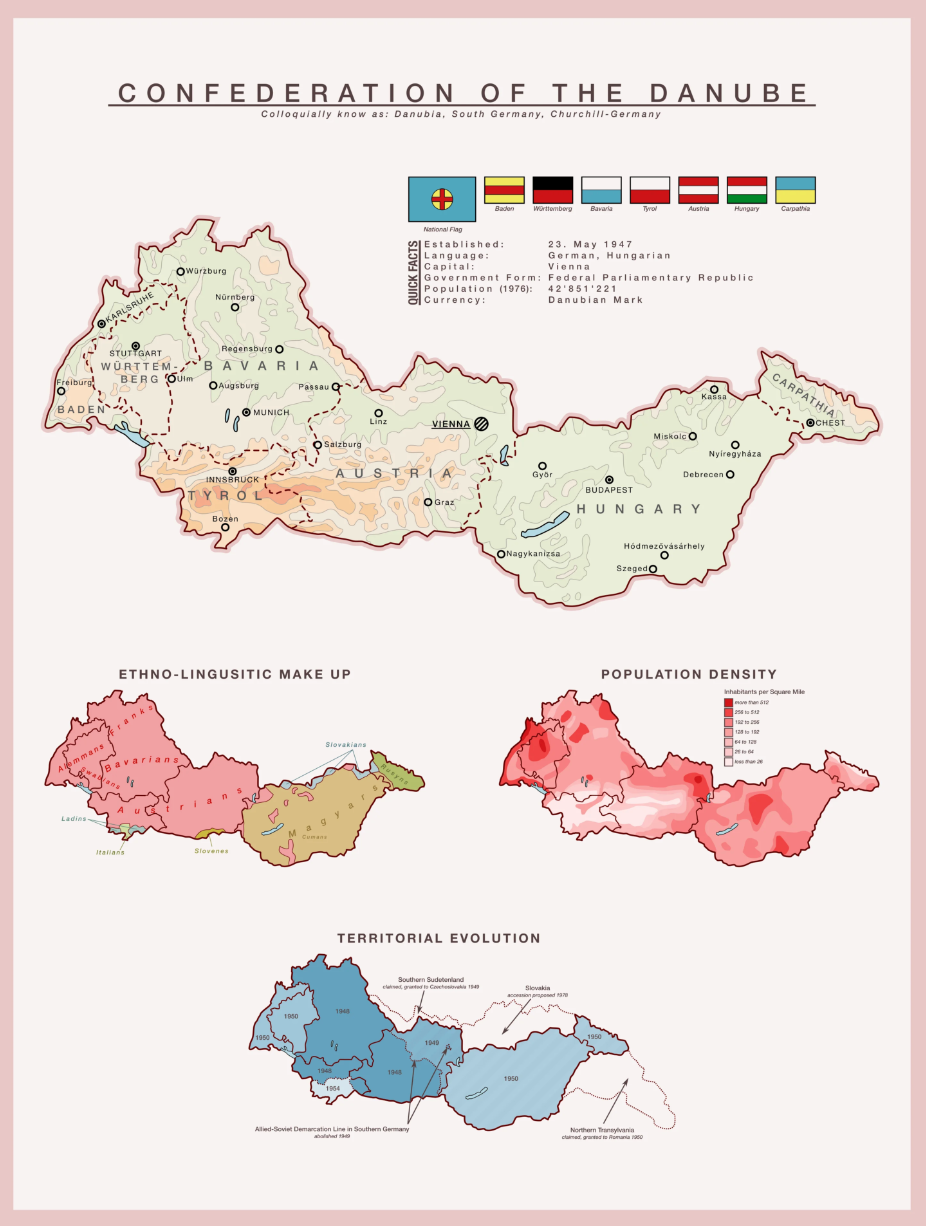

The wildest of all dismemberment plans was Churchill’s proposal for a Confederation of the Danube — firstly because of the size of the proposed state. The Confederation, a.k.a. Danubia or “Churchill-Germany,” would take in all of southern Germany (Bavaria, but also Baden and Württemberg), but also all of Austria and Hungary, plus even Carpatho-Ukraine (in the very east).

“Operation Unthinkable” was… unthinkable

Was Churchill attempting to revive the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian empire? No — the British PM was worried about Soviet encroachment into Central Europe, and by tying Hungary and Austria to the southern part of Germany, envisaged a state both big and western enough to limit Stalin’s influence on its affairs.

There was little enthusiasm for Churchill’s plan – in a worst-case scenario, if the Soviets did manage to gain influence over Danubia, that would give Moscow leverage deep into western Europe.

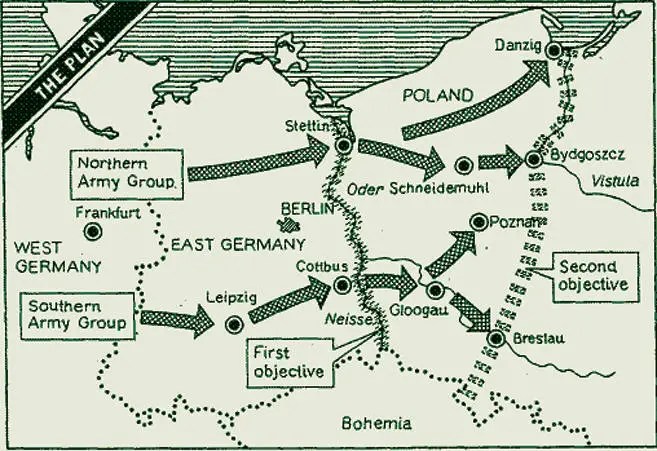

Eventually, it was decided to divide both Germany and Austria, as well as both capitals, into four occupation zones, one for each of the victorious Allies (the French now also counted among them). From there on after, history takes its familiar course. But at the time, the situation remained fluid enough for the British in May 1945 to draw up a secret plan for a surprise attack on Soviet forces in Germany, codenamed ‘Operation Unthinkable’.

Yet another plan that would have resulted in a different map of Europe, but that never came to be.

Strange Maps #1203

For more on Churchill’s plan for a Confederation of the Danube, check out this video by General Knowledge.

A good overview of several more plans to “dismember” Germany is here, at Never Was magazine.

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.