The coast-to-coast road trip is 120 years old

- In 1903, many still thought the “horseless carriage” was a passing fad, with limited practical use.

- Eager to prove them wrong, Horatio Jackson made a bet that he could drive a car across the country.

- 63 days later, Jackson, his driver, and Bud the bulldog had completed the very first coast-to-coast road trip in American history.

The coast-to-coast road trip, that American essential, turns 120 this year. In 1903, Horatio Jackson and Sewall Crocker became the first people ever to drive a car from one side of the U.S. all the way to the other.

Cars were an exciting novelty at the time, and their numbers were exploding — from 8,000 in 1900 to 32,920 in 1903 — but many still considered the “horseless carriage” a passing fad. There were few suitable roads, let alone a nationwide road network. So theirs was an adventure like none before. And it all started with a $50 bet.

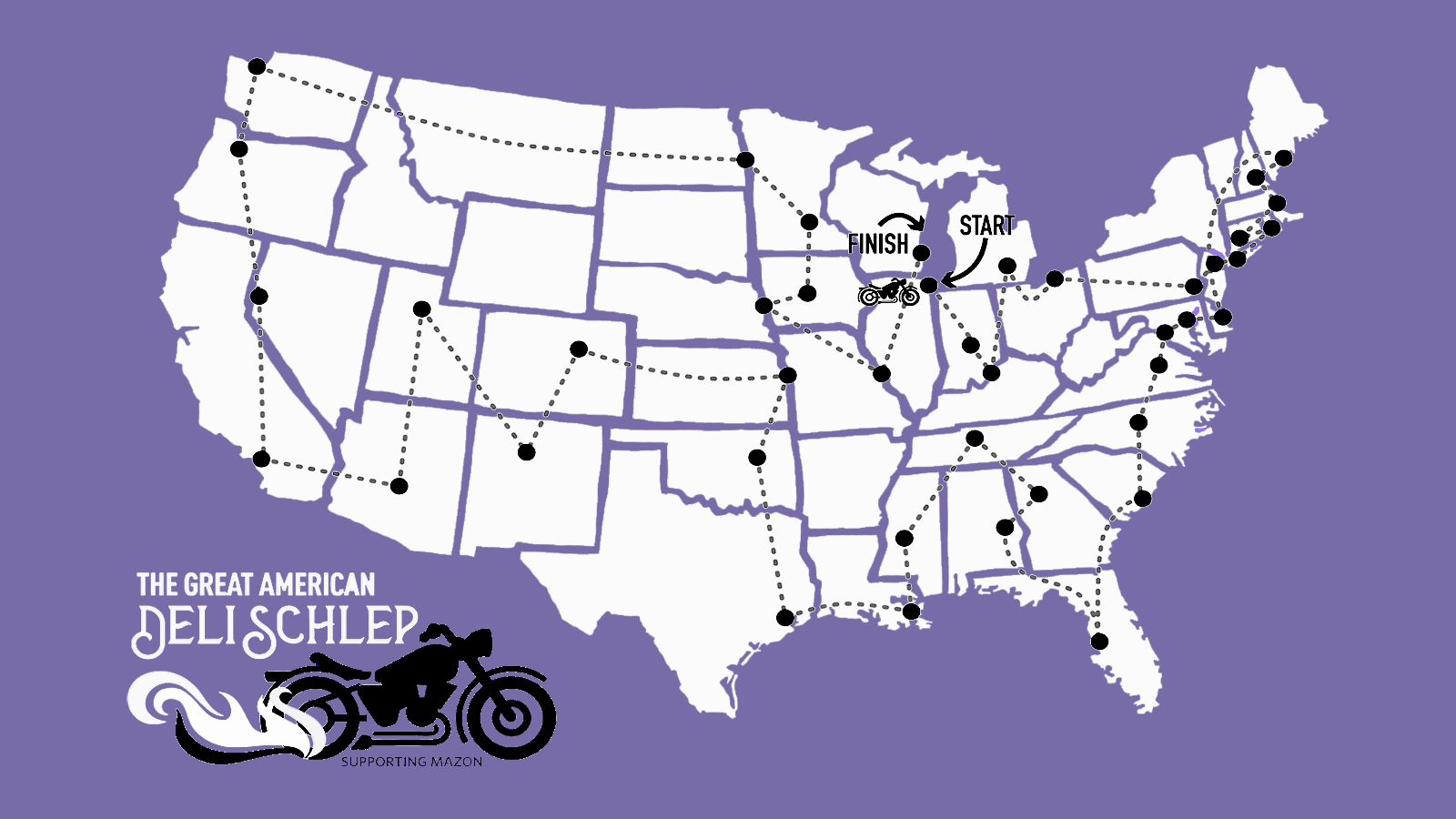

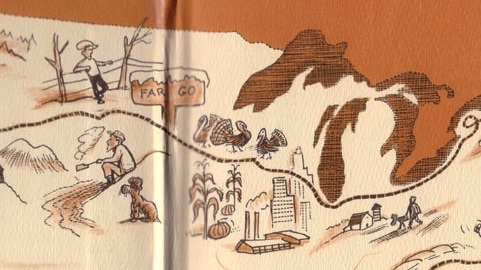

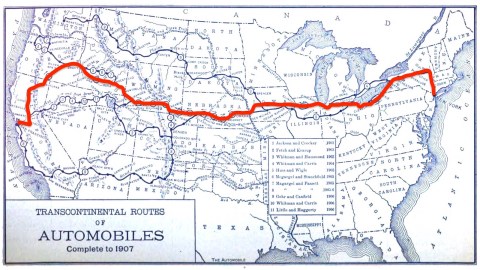

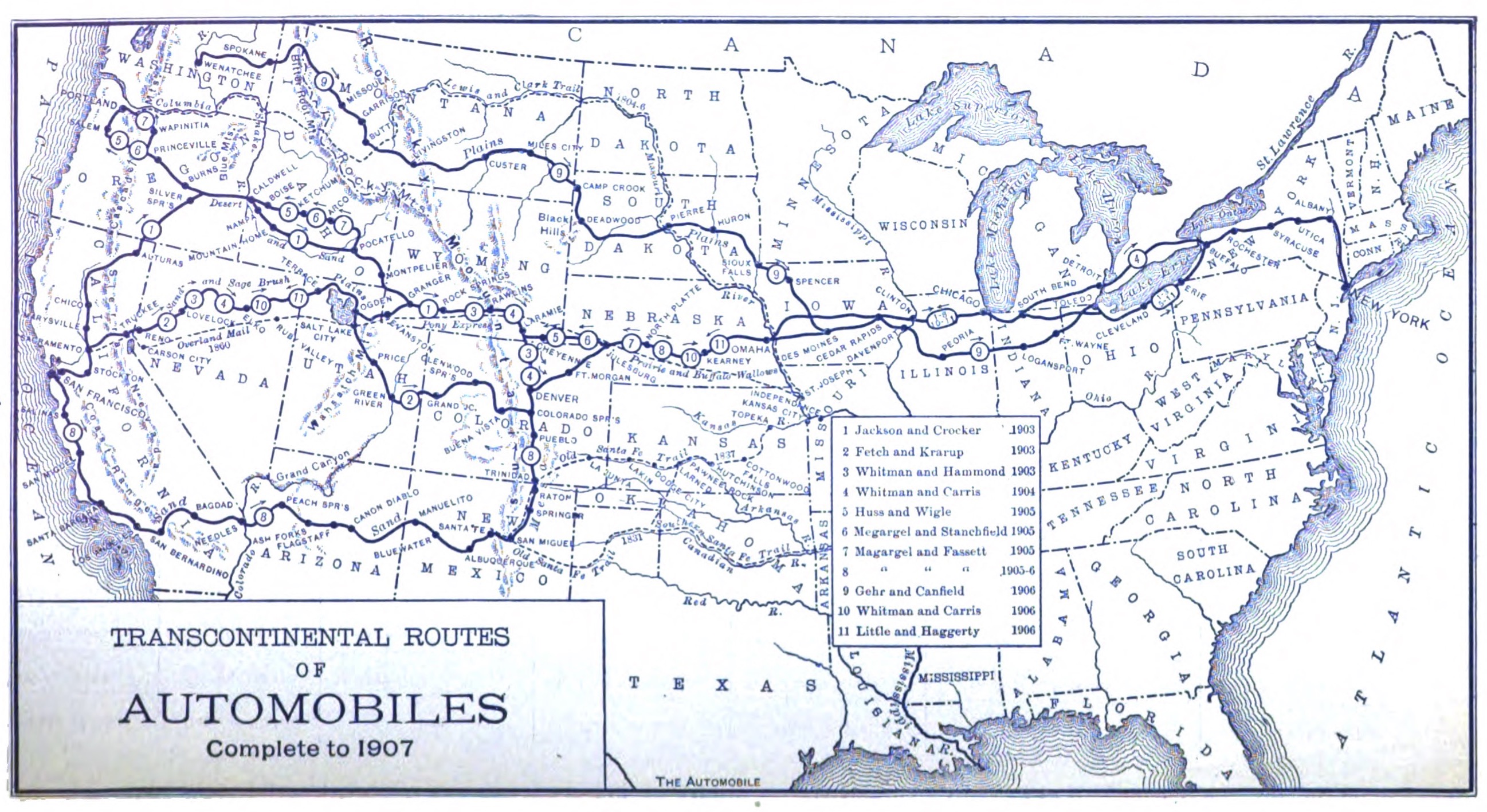

This map is from the 1907 edition of the Automobile Association of America’s Blue Book. It shows the routes of all the cross-country car trips completed until then: no more than 11 in total — and strangely, all duos. (The Jackson-Crocker trip is highlighted in red.)

Horatio Nelson Jackson (1872-1955) was a medical doctor from a prominent Vermont family. One of his brothers was mayor of Burlington. (John Holmes Jackson won the 1917 mayoral election with a margin of just 10 votes, a record matched by Bernie Sanders in 1981). Another was lieutenant governor of the state.

No maps, no car, and very little driving experience

Dr Jackson was an early automobile enthusiast. While in San Francisco (which he and his wife had reached by train), he accepted a bet that he could drive a car cross-country. He took the wager despite not owning a car, having very little driving experience, and not being in possession of any useful maps.

For such practical matters, Jackson enlisted the help of Sewall K. Crocker, a driver and mechanic, and on his advice purchased a 1903 Winton. He named the two-cylinder, 20-horsepower touring car “The Vermont.” The two left San Francisco on May 23, their car stuffed with sleeping bags and blankets; rubber suits and coats; an axe, a shovel, and other tools; a Kodak camera and a telescope; a rifle and a shotgun; spare parts; and as many cans of gas and oil as they could stow.

The plan was to avoid the deserts of Nevada and Utah and the higher passes of the Sierra Nevada and the Rockies, so the expedition swung north to follow the Oregon Trail in reverse. They were only 15 miles into the journey when the car blew a tire, and they had to use the only spare they had brought.

North of Sacramento, a woman misdirected them for a total of 108 miles so her family could see their first automobile. When more tires blew out on the rocky road towards Oregon, they wound rope around the wheels. Along the way, they wired the Winton Company for supplies to be sent ahead. Nevertheless, they occasionally had to walk or cycle long distances to find gas, oil, or spare parts.

A bulldog named Bud

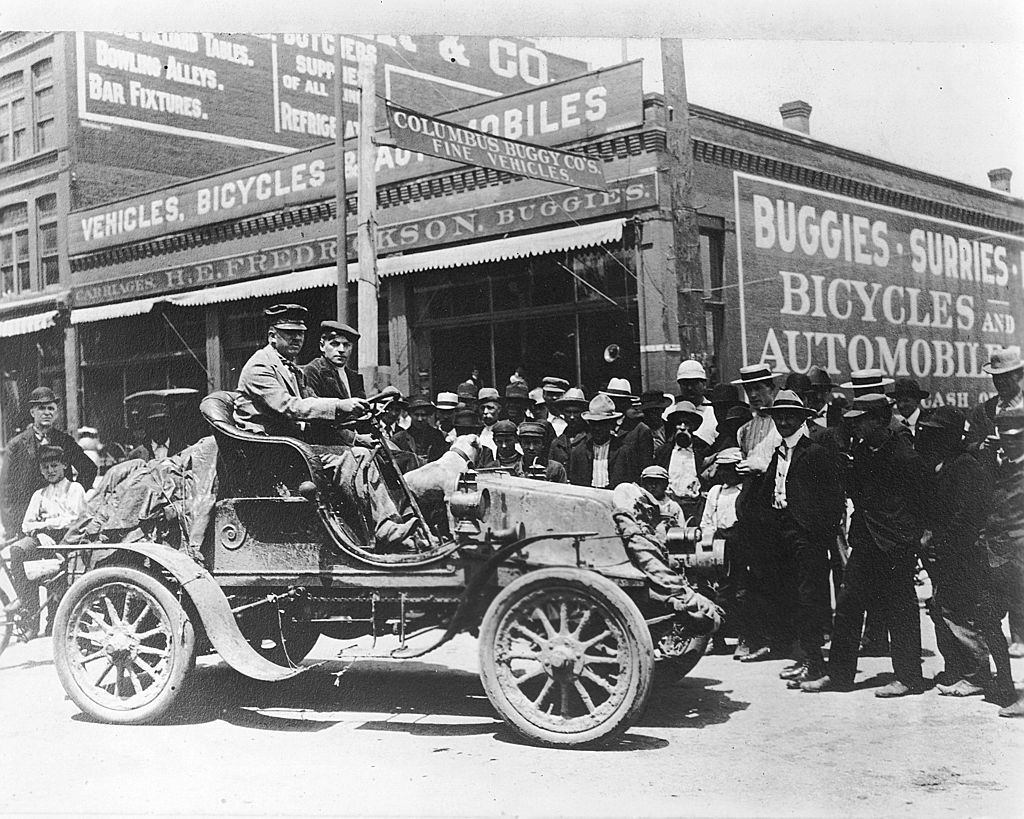

In Idaho, Jackson and Crocker acquired a bulldog named Bud as a traveling companion — and fitted him with goggles to keep the dust from his eyes. And then the press caught on. Jackson, Crocker, and Bud became celebrities. Reporters, and ever larger crowds, awaited the trio at every stop.

Despite more hardships — they lost their money and their way on the road to Cheyenne, forcing them to go without food for 36 hours — things got easier once they crossed the Mississippi, as there were more paved roads in the eastern half of the country.

When they arrived in New York City on July 26, 63 days after leaving San Francisco, they had completed the first cross-country road trip in American history. And it only took them about $8,000 ($260,000 in today’s money), financed entirely by Jackson, and 800 gallons (3,000 liters) of gas. They never collected the $50 wager.

Bud retired to Vermont with Jackson and his wife. Jackson went on to receive multiple medals for his active service in World War I and became a successful businessman in Vermont. His only other car-related feat of note is a traffic ticket for breaking the 6-mph speed limit in Burlington. In 1944, he donated his car to the Smithsonian Institution. It is on permanent display at the National Museum of American History in Washington DC, with the added likenesses of Jackson and Bud. (Crocker died in 1913 at the young age of 30, but that is hardly a reason for leaving him out.)

The cross-country adventures of Jackson and Crocker bring to mind a few other long-distance record breakers, such as Lewis and Clark or Phileas Fogg (the latter admittedly fictional). Their groundbreaking trip was the subject of a book (Horatio’s Trip) and a Ken Burns documentary of the same name, with Tom Hanks voicing Horatio Jackson.

No household names

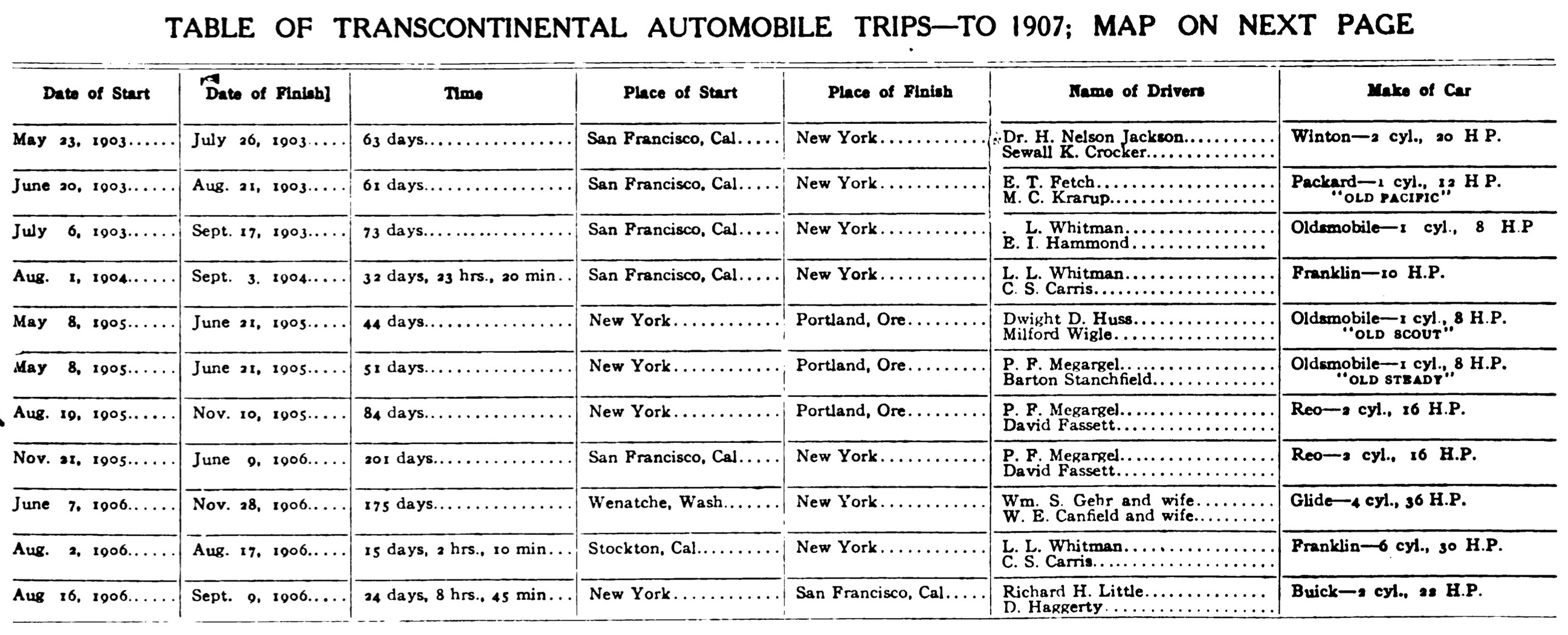

Despite the book and the documentary, the pair have never quite become household names on par with aviation pioneers like Charles Lindbergh or Amelia Earhart. The cross-country adventurers who followed in their tire tracks and are even less remembered, though they are on this map. This table, also from the 1907 Blue Book, brings their accomplishments back from oblivion for just a moment. (Here’s an animated version of the map, showing all 11 trips in sequence.)

Jackson and Crocker hadn’t even arrived in New York when two further car expeditions left San Francisco for New York. E.T. (“Tom”) Fetch and M.C. Krarup would get there in 61 days, two days faster than the originals. Lester Whitman and Eugene Hammond took 73 days, setting a slowness record.

A year later, Whitman got his revenge. With his new teammate Charles Carris, he shaved off almost a month of the previous record, driving from San Francisco to New York in just under 33 days. In so doing, Whitman became the first person to drive coast to coast twice.

There were no fewer than four coast-to-coast drives in 1905. Reversing the direction, the first three left from New York to arrive in Portland, Oregon. The first two were obviously in a race against each other, both leaving on May 8, and both in eight-cylinder Oldsmobiles.

Three hurrays for Percy Megargel

But who won? The table says Dwight Huss and Milford Wigle completed the crossing in only 44 days, versus 51 days for Percy Megargel and Barton Stanchfield — but it shows both teams arriving on 21 June. It seems likely Megargel lost (arriving on June 28 instead of June 21), because he went straight back and tried again, this time with David Fassett. Their time was a disappointing 84 days. The pair returned to New York by car, setting off from San Francisco, but the result was even worse: 201 days. At least Megargel was the first person ever to drive coast-to-coast three times.

The year 1906 saw three coast-to-coast road trips. William Gehr and W.E. Canfield brought their wives with them — also a first. Whitman and Carris broke their own speed record, crossing the country in just over 15 days. Richard Little and D. Haggerty, arriving in San Francisco 24 days and eight hours after leaving New York, would have made headlines just two years earlier. But by that time, the novelty, if not the attraction, of coast-to-coast road trips had already started to wear off.

Final note on Horatio Nelson’s ‘maiden’ trip:

As the road transport paradigm shifts from fossil fuels to electric, there’s a whole bunch of early automotive records now ripe for a do-over. Including Horatio Jackson’s coast-to-coast road trip. In 2022, Jack Smith and two friends did just that. They retraced Horatio’s route in a 1964 VW Bus that had been converted into an electric vehicle. It went well enough for them to immediately double back: “Once we reached New York City, we turned around and followed the 1913 version of the Lincoln Highway back to San Francisco”, Jack writes. Read all about that trip here.

Strange Maps #1201

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow strange maps on Twitter and Facebook.