This shell is not just a symbol, but also a map

- For Catholics, the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela — in Galicia, an autonomous region tucked away in the northwestern corner of Spain — is arguably the third most important in the world.

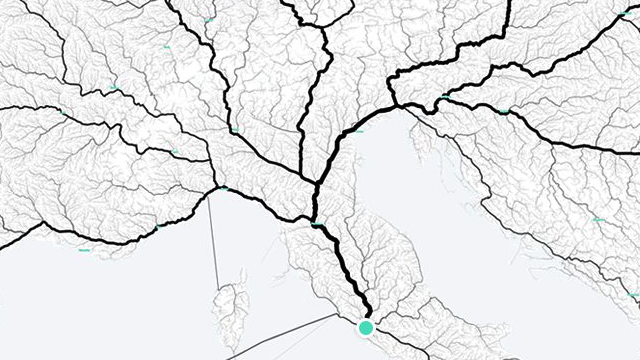

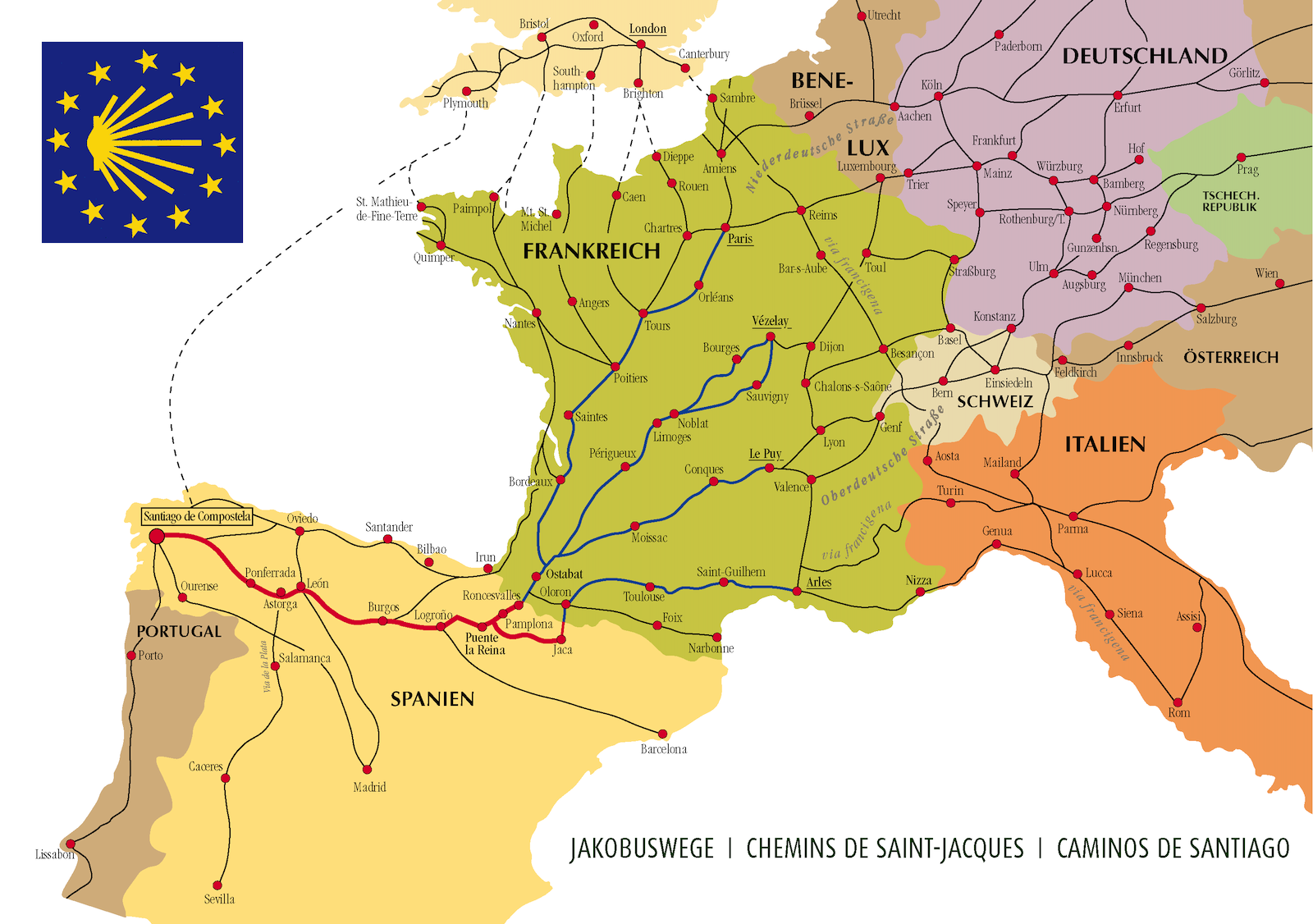

- The Road of St James (or Camino de Santiago) heading toward Compostela is made up of many separate paths, which come together the closer they get to their destination.

- Similarly, the radial riblets on the exterior of a shell converge in a single point, symbolizing the tomb of St James in the Cathedral of Compostela.

An epiphany, but not of the religious kind. As I’m looking at the map, my eyes dart back and forth between the forking roads and the symbol in the map’s upper left corner. Then there’s a sudden flash of cartographic illumination.

Encircled by the 12 gold stars of the European Union (and the Virgin Mary), the pictogram represents a scallop shell, which for various legendary reasons is associated with the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. But the shell — and here’s that cartographic flash — also represents the Camino itself.

Third most important pilgrimage in Christendom

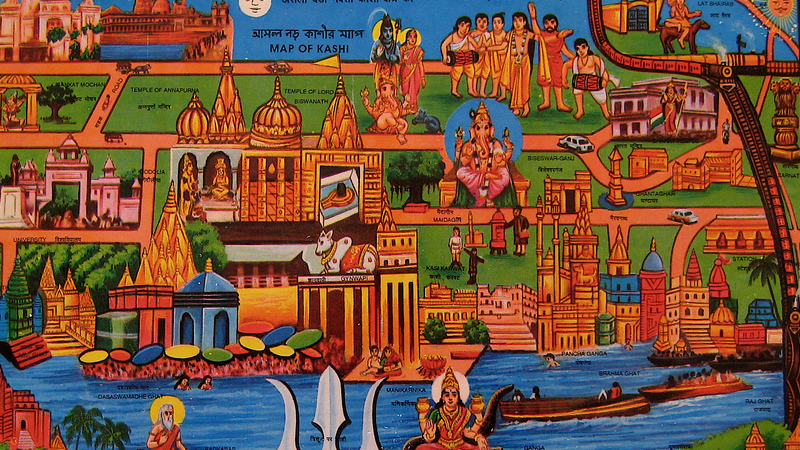

Compostela (population: 100,000) is the capital of Galicia, an autonomous region tucked away in the northwestern corner of Spain, north of Portugal. Pious legend has it that the remains of St James the Great, one of Jesus’ 12 apostles (and known in Spanish as Santiago), were discovered here in the 9th century.

Those holy relics started attracting pilgrims; local ones at first, but later, from as early as the 10th century onward, they came from across all of Europe. Since the Middle Ages, Santiago has been the third most important pilgrimage in Christendom, after those to Jerusalem and Rome.

As the map shows, the Road of St James (or Camino de Santiago) heading toward Compostela is made up of many separate paths, which come together the closer they get to their destination. Similarly, the radial riblets on the shell exterior converge in a single point, symbolizing the tomb of St James in the Cathedral of Compostela.

The scallop, in other words, is also a map, albeit a rather rudimentary one. But it’s even more. The symbol is in frequent use along the Camino as a direction sign: an arrow, whose riblets point pilgrims the right way toward their destination.

Proof of completion

In earlier times, pilgrims brought home a scallop shell, very abundant off the coast of Galicia, as proof that they had completed their quest. Those noble enough to have a family crest often included a shell on their insignia, as a more permanent proof to posterity. These days, pilgrims wear a scallop shell already on the way over to Compostela, as a visible sign (to others) and reminder (to themselves) of the task ahead.

The most popular part of the network of roads leading to Compostela is the French Way (Camino francés), which despite its name also applies to the final stretch on the Spanish side. According to the to the Oficina del Peregrino, which keeps annual statistics on the pilgrims arriving in Compostela, about 60% of pilgrims do so via this route.

The French Way starts out as four separate paths. Three of these, starting in the French cities of Tours, Vézelay, and Le Puy, converge at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port on the Spanish border. They continue for another 485 miles (780 km) on the Spanish side as a single route, passing through such historical cities as Pamplona, Burgos, and León.

The fourth branch starts in Arles, crossing into Spain farther east and following the Aragonese Way before merging with the French Way in Puente la Reina, south of Pamplona.

Religion ebbs, but pilgrimages rise

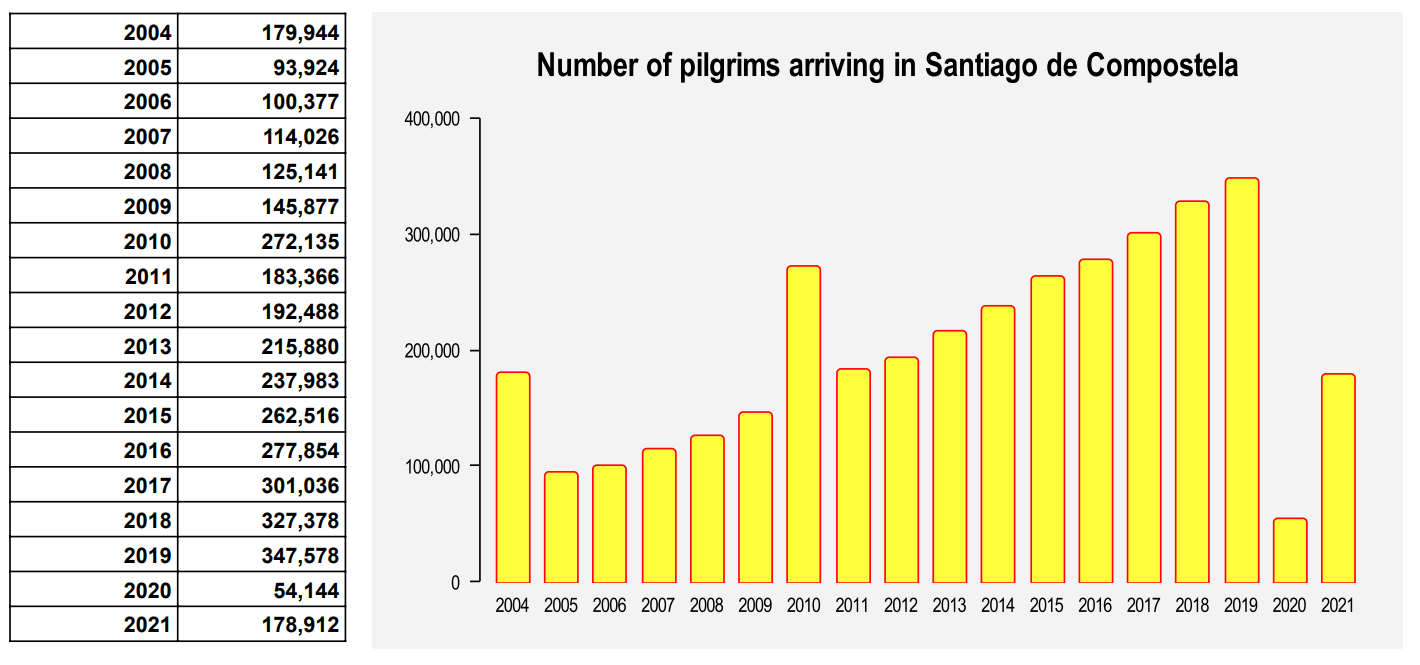

Over the past decades, the Camino has been rising in popularity, which stands in paradoxical contrast to the ebbing tide of religiosity in Europe. Here’s an overview of the number of pilgrims arriving since 2004, the earliest year the Oficina del Peregrino has figures available:

Two years with atypically high numbers stand out: 2004 and 2010. These were Holy Years — years in which the feast of Saint James the Elder falls on a Sunday. This happens in a recurring sequence of six, five, six, and 11 years apart.

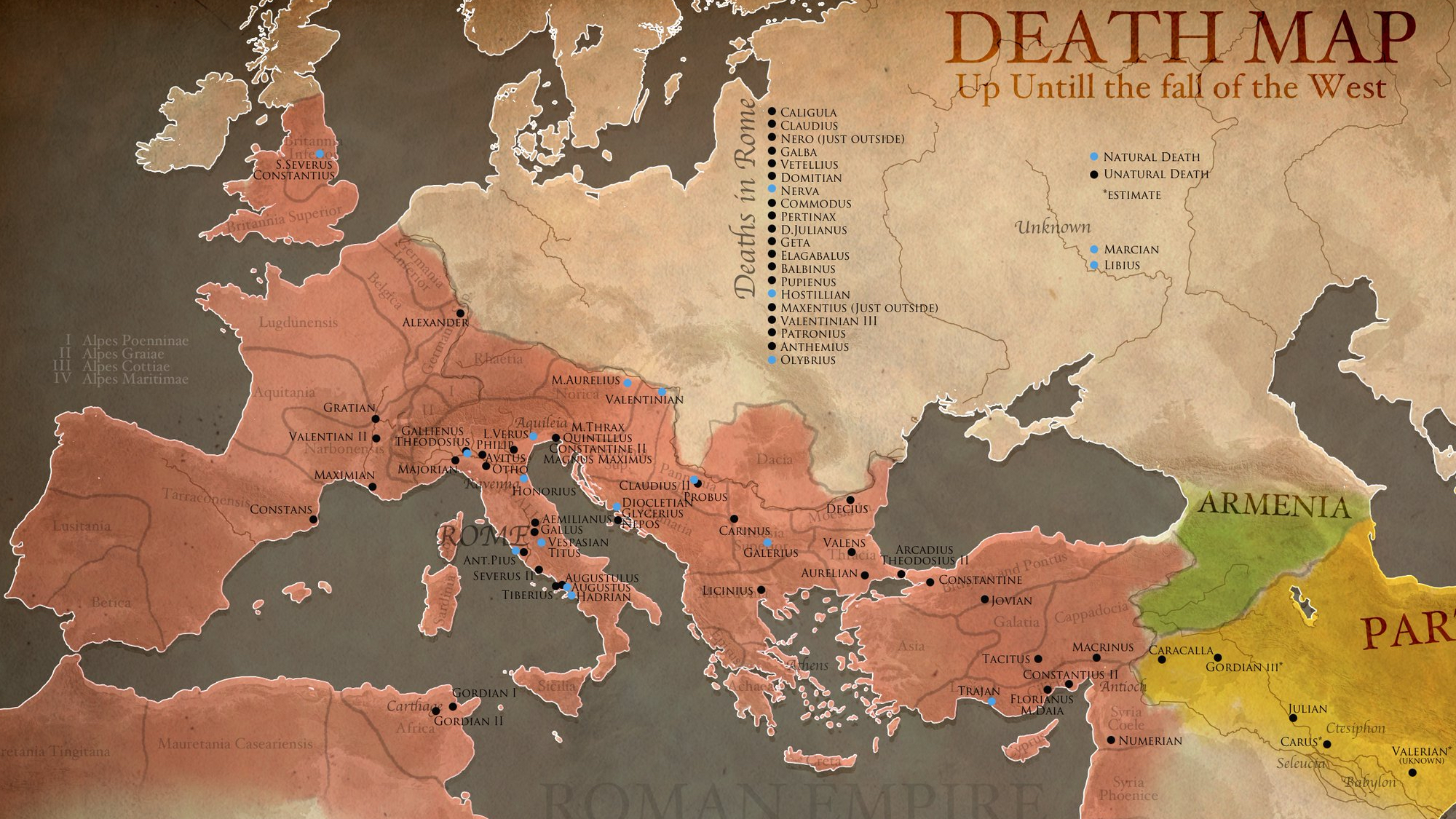

For Catholic pilgrims, this means they can obtain the plenary indulgence (i.e. forgiveness for sins) on any day of the Holy Year. To obtain this indulgence, also known as the Jubilee, pilgrims must fulfill a number of conditions.

Holy Years and Holy Doors

These include praying, receiving the sacraments of confession and communion, and entering the Cathedral of Santiago via the Holy Door, which is opened only in Holy Years. (The Catholic Church has designated eight Holy Doors the world over: four in Rome, the one in Compostela, plus one each in France, Québec, and the Philippines).

Open Holy Doors aside, the number of pilgrims arriving in Compostela has risen steadily, typically by about 10% each year, from around 90,000 in 2005 to nearly 350,000 in 2019. Arrival numbers crashed in 2020 because of the pandemic. Attendance in 2021 — the second Covid year and 11 years after the previous one another Holy Year — was up, but not yet back to pre-pandemic levels.

The Oficina del Peregrino reveals a few interesting statistics about the 2021 arrivals.

- The total number of pilgrims arriving at Compostela was almost perfectly divided between men (50.5%) and women (49.5%).

- Nearly 94% arrived on foot, just over 6% on a bicycle. Also: 199 people made the pilgrimage on horseback, and 37 in a wheelchair.

- Just over a third (36%) came for religious reasons. A solid fifth (20%) didn’t. The rest came for “religious and other” reasons.

- Most pilgrims (58%) were between 30 and 60 years old. But of the rest, more (26%) were younger than 30. Just 16% were over 60.

- By far the largest contingent of pilgrims (68%) came from Spain itself, with Portugal (5%) a very distant second, followed by Italy (4.4%), Germany (3.7%), and a surprisingly large contingent from the U.S. (3.2%, i.e. more than 5,500 pilgrims). Completing the top 10 were France (2.5%), Poland, the Netherlands (both 1%), Mexico, and the UK (both 0.8%).

- Among the rarest nationalities completing the pilgrimage were Togo, Tunisia, Sri Lanka and the Falkland Islands (each just one); and Bangladesh (2), Liechtenstein (3), Syria (4), and Namibia (5). Perhaps the most surprising contingent are the 12 Saudi nationals, citizens of a country where adherence to Islam is mandatory.

Whether they’ve come long or far, and by whatever means, pilgrims to Compostela converge on the city like those lines of different lengths do on the scallop shell. They are united by the place where their lines converge, whether they arrive to seek forgiveness, or merely rehydration.

Strange Maps #1171

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.