The Short Life of Little Germany, New York’s First Ethnic Enclave

Almost 113 years ago, New York suffered the second-deadliest disaster in its history. Only 9/11 would claim more lives than the wreck of the General Slocum[1] on 15 June 1904.The 1,021 people who burned alive on board or drowned in the East River while fleeing the flames represented a single, but pivotal percent of Little Germany. Their deaths hastened the demise of one of Manhattan’s oldest ethnic enclaves.

Little Germany was the first major non-Anglophone ethnic enclave in New York. Though little remains of it today, its start (in the 1850s), flowering (from the 1870s) and eventual disappearance (by the 1920s) beat a path through New York’s urban jungle followed by countless other ethnic neighbourhoods since – if only by its fluidity and impermanence.

The enclave started small, in New York City’s 11th ward. It was centred around Tompkins Square, which the Germans called der Weisse Garten (‘the White Garden’), in an area now known as Alphabet City. Eventually, it would include 400 city blocks on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Known to its inhabitants by the diminutives Kleindeutschland or Deutschländle (the second a distinctly southern German variant), Little Germany was also called Dutchtown [2], mainly by the Irish immigrants who dominated a few of the neighbouring wards.

Germans had been migrating to North America ever since a Dr. Johannes Fleischer was present at the founding of Jamestown in 1607, thus becoming the very first documented German-American. The greatest influx of Germans occurred between 1820 and 1914, when a total of 6 million made it to the US [3].

Many came in through Ellis Island, and a lot of those stayed in New York. In 1860, the city counted over 120,000 German-born inhabitants, making New York the world’s third-largest German-speaking city, after Berlin and Vienna.

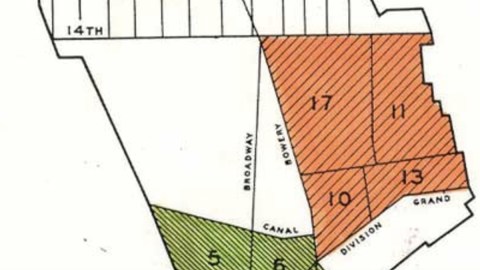

The new arrivals repeated a common migration pattern: they sought out the mutual support network created by compatriots who had preceded them, thus reinforcing the ‘German’ character of a specific area. Kleindeutschland was riddled with German schools and churches, hospitals and shops. Much of the social glue was provided by sports clubs, shooting associations and Gesangvereine (i.e. singing societies) [4].Around 1870, Kleindeutschland encompassed much of the Lower East Side, from 14th Street in the north to Division and Grand Streets in the south. The East River formed its natural boundary to the east, while its western end coincided with the Bowery, except between Houston and Canal Streets, where it extended to Mott Street; and in the north (where the Bowery turns into4th Avenue), and it only went as far as 3rd Avenue.

To outsiders, Little Germany may have appeared a chaotic cauldron of otherness, but like many ethnic enclaves before and since, it was in fact itself a delicate balance of the regional differences back home. Germans from particular areas in the old country tended to congregate in the same neighbourhoods of their new home.

- The 10th ward saw the heaviest concentration of Prussians, who by 1880 represented about 30% of the city’s German-born population.

- In the 1860s, the 13th ward was the focal point for Hessians, who later migrated north towards the 11th and 17th wards. By the 1880s, the 13th ward had become a popular destination for immigrants from Baden. And particularly for Hanoverians, who formed their own ‘Little Hanover’ in the 13th.

- By the 1860s, Wurttembergers had started moving into the 17th ward, from areas further south.

- Curiously, Prussians and Bavarians seemed repelled by each other’s presence. Bavarians were spread evenly throughout Little Germany, but usually inversely with Prussians. They were fewest in the ‘Prussian’ 10th ward.

Little Germany peaked in the 1870s. By then, successful residents would celebrate their accession to the American middle class by moving away from their roots, both geographically and culturally. They were replaced by first-generation immigrants from other backgrounds. So Kleindeutschland was already on the decline in 1904, when the local St. Mark’s Lutheran Church organised its 17th annual summer picnic.

The German church had chartered the paddle steamer General Slocum to transport 1,300 of its congregants to a picnic spot on Long Island. As the three-decked ship passed 81st Street, a fire broke out in the lamp room.

The captain first disbelieved, then underestimated the fire. The ship’s rotten firehoses proved useless to fight the blaze, its broken lifeboats incapable of providing an escape from it. When flames engulfed the ship, victims either burned to death or jumped overboard to drown in the river. Fewer than 300 passengers survived.

The General Slocum disaster broke the spirit of the local community. Recriminations reverberated, outward migration accelerated. There was a marked increase in the number of suicides in the area. Kleindeutschland evaporated – also because the area remained a focus for immigration. The Lower East Side became a centre of Jewish life, later of Portorican and Dominican immigration – and more recently of gentrification.

As an earlier map posted on this website shows, the borders and names of Manhattan neighbourhoods are very much up for discussion. Especially if they reflect an ethnic reality, these names become obsolete as that reality changes. What was once known as Little Italy has been absorbed almost entirely by Chinatown (which itself is sprouting such subdivisions as ‘Little Fuzhou’, after immigrants from China’s Fujian province). Spanish Harlem was better known as Italian Harlem before 1940. And Loisaidia, deriving from the Hispanic pronunciation of ‘Lower East Side’, denotes an area of Alphabet City around Avenue C, in what used to be known as Little Germany.

Perhaps Little Germany’s most enduring legacy in New York is that diminutive, still the natural prefix for any area dominated by a particular ethnicity. Apart from that vestigial Little Italy, New York today also boasts a Little Greece and a Little Poland, a Little Brazil and a Little Egypt, and not only a Little India but also a Little Punjab, and even two Little Pakistans. And that’s not even including areas named after cities rather than countries, like Little Saigon and Little Manila.

For more on the General Slocum disaster, see this piece in the Magazine at BBC News . The black and white map of Kleindeutschland taken here from this genealogy article on Stride Writer, the personal website of Gene Landriau. The map of NYC wards taken here from Demographia, a website dedicated to urban development. The colour map of the German and Irish wards in lower Manhattan taken here from what appears to be a defunct websitededicated to the General Slocum disaster.

Strange Maps #663

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] The incident is mentioned in James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is set one day after the disaster, on 16 June 1904: “Yes, sir. Terrible affair that General Slocum explosion. Terrible, terrible! A thousand casualties. And heartrending scenes. Men trampling down women and children. Most brutal thing. What do they say was the cause? Spontaneous combustion. Most scandalous revelation. Not a single lifeboat would float and the firehose all burst. What I can’t understand is how the inspectors ever allowed a boat like that… Now, you’re talking straight, Mr Crimmins. You know why? Palm oil. Is that a fact? Without a doubt. Well now, look at that. And America they say is the land of the free. I thought we were bad here.” ↩

[2] Thus repeating the common confusion in English between the people and language of the Netherlands (Dutch in English, Nederlanders and Nederlands in Dutch) and the people and language of Germany (German in English, Deutsche and Deutsch in German). See also Dutch Country in Pennsylvania, named after Germans who spoke Deutsch, not people from the Netherlands who spoke Dutch. The original confusion of course was naming the language of the Netherlands Dutch and not Netherlandic. ↩

[3] There are close to 50 million Americans of German descent, representing 17% of the population, and making German-Americans the largest ethnic heritage group in the United States, before African-Americans (41 million), Irish-Americans (35 million), Mexican-Americans (32 million), English-Americans (27 million), Italian-Americans (17 million), Polish-Americans (10 million) and French-Americans (9 million). Intermarriage has of course blurred these categories, which are often reported with different figures, depending on how you count. More info here. ↩

[4] Perhaps the most prominent singing society was the Deutscher Liederkranz, which had about 350 members by 1860, and over 1,000 by 1870. At that time, its leaders were the piano manufacturer William Steinway and Oswald Ottendorfer, publisher of the New-Yorker Staats-Zeitung, a major German-language newspaper. By 1863, a Liederkranz Hall was built on East 4th Street. By 1881, it was moved north to East 58th Street, mirroring the northward migration of German-Americans themselves. The Liederkranz, also known by its abbreviation as Elka, lives on in the name of Elka Park, a summer holiday spot in the Catskills in upstate New York, founded by and for wealthy German-Americans. ↩