641 – A Whale of a Story, for Goldfish: The Voyage of the Pequod

Call me a quitter. But I never did finish Moby Dick. Herman Melville’s writing is magnetic – in both senses of the word: attractive for its beauty and passion, and repellent because of its obsessive and digressive voluminosity. Clearly, the book was written in and for an age when neither writer nor reader had to contend with the inescapable distractions of a 24/7 news cycle, and an internet brimming with cat videos, bieberiana and other hilarious banalities. When people had memories like elephants, not the attention span of a goldfish.

I don’t remember whether I gave the tome two or three tries, setting off to sea with the protagonist, paddling as far as the middle of the book, before abandoning ship at one of those chapters exhaustively describing whale dentistry or some other obscure aspect of cetaceans in general, or whaling in particular. Finally, I tried the audiobook, more precisely the Moby-Dick Big Read, which matches the original in its obsessive intricacy: the 136 chapters are each read by a different luminary– some cleverly paired to a chapter relevant to their craft – and accompanied by a visual work of art. (It’s available online and downloadable for free, if you want to give it a stab).

But even the novelty of hearing the chapters read by the likes of Tilda Swinton (§1: Loomings), David Cameron (§30: The Pipe), China Miéville (§59: Squid) or Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall (§65: The Whale as a Dish) proved too little icing for altogether too much cake. Long before I got to the chapter read by Sir David Attenborough (§105: Does the Whale’s Magnitude Diminish?), the one thing that had crucially diminished, was my will to read on.

And yet, like Ahab, I cannot rest until I have slain this leviathan. I am determined one day to make it to the end. And I’m never more determined than when I am not holding the book. For it is such a sprawling mess, such a disastrous failure of literary zoning laws, that from the now-familiar shores of the island of Manhattoes, whence Ishmael and I have by now set sail so often for the whaling ports of New Bedford and Nantucket, it is impossible to preview its finale in all but the most general terms – including in geographical terms. Unlike Ulysses, that other great unread novel, which at least has a clear event horizon (Dublin, 16 June 1904), Moby Dick seems as unconfinable to time and place as the waves themselves. This unnerving sense of dislocation doubtlessly contributes to the forbidding shadow the book casts before it.

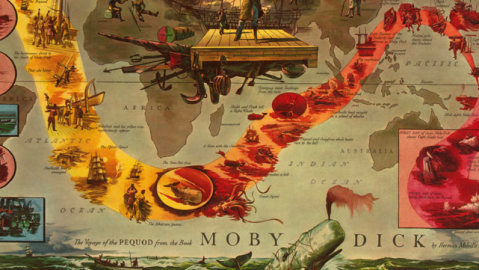

Fortunately, there is a map. And it does what maps do best: it shows us the way, reassuring us that even the longest voyages have an end as certainly as they have a beginning. The map’s title is The Voyage of the Pequod, showing the route of that ill-fated ship captained by Ahab, obsessed with exacting revenge on the white monster that took his leg on a previous whaling trip. Among its crew are the narrator Ishmael, his savage friend Queequeg, and Starbuck (who indeed lent his name to the coffee chain, after the initial proposal, Pequod, was rejected by some of the founders).

The map shows us the course of the Pequod, incidentally validating the map of 19th-century American shipping traffic, shown a few posts earlier. For the ship follows several of the densest datastreams on that map: setting out from New England, it plunges down the Atlantic Ocean, between West Africa and South America, to round the Cape of Good Hope and traverse the Indian Ocean in a northeasterly direction, passing between Java and Sumatra and past the Philippines into the Pacific Ocean, then sailing south to meet its doom somewhere off New Guinea.

The story’s geographic progression is accompanied by illustrations of its narrative evolution. Early on, Captain Ahab convinces his crew of his particular mission (The harpooners drink to the death of Moby Dick), whales are sighted in the North Atlantic (Thar she blows), and the Captain’s strange confidant arrives (Fedallah and his yellow crew mysteriously appear).

Ominousy, the ship’s course gradually acquires an increasingly blood-like tint as the voyage progresses, as the story seems to get more grim: Stubb makes a kill, then the Pequod and Jungfrau whale boats race to the kill, and Stubb and Flask kill a Right Whale.

As the ship sails into the Pacific, the object of Ahab’s obsession comes into focus (Capt. Boomer of the Enderby lost an arm to Moby Dick) even as circumstances for the crew grow even more worrisome (Pip overboard; Watch overboard; the typhoon). Finally, Ahab sights Moby Dick, and the sea itself turns red.

A cartouche then zooms in on the final stages of the story – the deadly encounter between the Pequod and the whale. On the FIRST DAY of chase – Moby Dick chews Capt. Ahab’s boat, while on the SECOND DAY of chase – Ahab’s boat is tossed; the Parsee is lost; Ahab’s ivory leg is broken. Finally, on the THIRD DAY of chase – Moby Dick sinks the Pequod. All go down with her, but Ishmael alone survives in the coffin canoe.

There! That saved me about two months of my life, and was even quicker than those graphic-novelisations that seem the only chance most of us will ever get to read those 19th-century classics and still check our email.

A weight lifted off my shoulders! Now, where’s that map of Ulysses. Ah, here!

Many thanks to John Pittman, Alessandro Martins and Lambert Teuwissen, who sent in this map. It was designed by New York commercial illustrator and muralist Everett Henry, in a series of 12 literary maps published by the Harris-Seybold printing company of Cleveland between 1953 and 1964, eventually as part of a calendar, to demonstrate their lithographic capabilities. The image was taken from this page of the Library of Congress, the zoomed images were taken here at the University of Chicago Press.