France’s Failed Attempt to Turn the Sahara Desert into a Fertile Sea

In 1870s France, Ferdinand de Lesseps was a rock star. This was the man who had dared to dream the Suez Canal into being. Finished in 1869, the canal not only shaved off 6,000 km (nearly 4,000 miles) off the sea voyage from Europe to Asia, it also turned Africa into an island. De Lesseps was a world-changer. French public opinion hailed him as le grand Français; the imperial government made him a viscount.

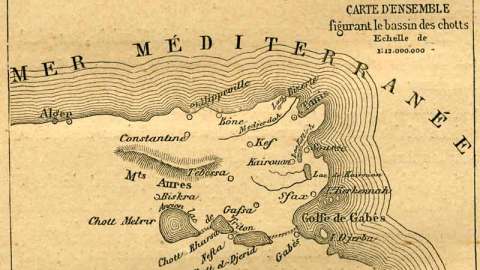

Casting about for the next world-changing scheme, de Lesseps fell upon a plan to create a giant inland sea in the North African desert. The idea was not his own [1], but it took the Great Frenchman’s seal of approval to propel the plan from obscurity to nationwide prominence.

François Élie Roudaire, a captain without a sea.

The father of the ‘Sahara Sea’ was François Élie Roudaire, a French army captain who had been tasked in 1864 with mapping the more inaccessible parts of Algeria, then a French colony [2]. In 1874, the military geographer was the first to establish that the so-called Chott[3]el-Mehrir, in the south of Constantine province and close to the border with Tunisia, was situated well below sea level [4].

Knowing his classics, Roudaire couldn’t help thinking that this submarine salt plain might once have been the seabed of the fabled Bay of Triton [5]. Described by Herodotus but unknown to modernity, the lake’s debatable existence and location constituted an Atlantis-type mystery popular among geographers. Could Chott el-Mehrir be contiguous with other chotts towards the Tunisian coast, forming a the ghostly imprint of a former sea inlet? And… could this semi-mythical body of water be resurrected?

Detailed overview of the chotts across the Algerian-Tunisian border. They are coloured in too optimistic a shade of blue.

In the immediate aftermath of de Lesseps’ triumph at Suez, a project of that magnitude might not have seemed impossible. But that still leaves the question: Why recreate that ancient sea at all?

Two words: mission civilatrice [6], the French take on the White Man’s Burden. On the eve of Europe’s Scramble for Africa, France’s grip on a large swathe of the continent – from the Maghreb to the West African coast – was already tightening. With it came plans to bring order and progress to the continent, perhaps in the form of a Trans-Sahara Railroad [7]; and why not by re-creating an inland sea that would bring commerce and agriculture to the otherwise useless desert…

Roudaire laid out his plan in the May 15, 1874 issue of the Revue des Deux Mondes. To reanimate the Bay of Triton as far inland as 380 km (235 miles) from the Gulf of Gabès, on the Tunisian coast, he proposed to breach the coastal ‘isthmus’ of 20 km (13 miles) wide and 45 m (150 feet) high and siphon Mediterranean water inland via a canal that would be 190 km (120 miles) long. The resulting sea would have an average depth of 23 m (78 ft) and a surface area of about 5,000 km2 (3,100 sq. mi), which is roughly double the size of Utah’s Great Salt Lake, or 14 times the size of Lake Geneva.

The admirable Triton: a map indicating the presumed location and extent of the ancient body of water.

The price tag: a mere 25 million francs [8]. A small investment with a large return. The reanimated bay would, so Roudaire thought, be big enough to alter the local climate, turning the surrounding desert into a breadbasket: a vindication of France’s enlightened policies, with tangible benefits for the local population. “The Sahara is the cancer eating away at Africa”, Roudaire wrote. “We can’t cure it; therefore, we must drown it”.

Perhaps Roudaire found it fitting that the Sahara Sea would not only bring progress and prosperity, but also fulfil an ancient prediction. Legend has it that the god Triton himself, seated on a brazen tripod, had foreseen that, when a descendant of the Argonauts would come and carry off that tripod from his temple, a hundred Grecian cities would be built around the lake. And wasn’t 19th-century Imperial France a worthy transmitter of the values and virtues of Antiquity? Creating what Roudaire called une mer intérieure africaine – a miniature Mare Nostrum[9] – would confirm France as a clear successor to the Roman Empire.

And yet, however high-minded the plan, Roudaire’s large inland sea would also serve a more cynical, military purpose: “Un canal, large et profond, isolerait le sud tunisien […] et aiderait la pacification de la region“. The Sahara Sea would isolate the rebellious tribes of southern Tunisia, making it easier to contain and subdue them.

Maximalist plan, with both the canal, and all to be submerged areas shown. Note the comparison map of Lake Geneva, inset lower right hand corner.

Roudaire didn’t just appeal to public opinion; he also made sure to address the Great Frenchman directly. In a letter to de Lesseps, he explained that creating the Sahara Sea would result in:

“an immense amelioration of the climate of Algeria and Tunis, since the moisture caused by the evaporation [10] from the vast expanse of water will be driven by the prevailing southerly winds over these countries, forming a layer of humid atmosphere which will greatly mitigate the intensity of the solar rays and retard the cooling of the earth by radiation during the night. The proposed sea, too, being navigable for ships of the greatest draught, will also open a new commercial route for the districts lying to the south of the Aurès [11] and the Atlas range; while watercourses which from the south, west, and north converge towards the shotts, but which are now dry during the greater part of the year, will again become rivers, as the once undoubtedly were, leading ultimately to the fertilisation of vast tracts of now desert land on their banks”.

De Lesseps bought into Roudaire’s vision. With Suez Canal Man on board, France’s political, scientific and literary elites followed suit. The Académie des Sciences supported the idea, and the French government provided Roudaire with a budget of 35,000 francs for a trigonometrical survey of the chotts towards the Tunisian coast.

In blue, the areas that are actually below sea level.

These expeditions must have been the high water mark of Roudaire’s life. He was promoted, to chief of squadron. Great things were expected of him – to be the next French world-changer. And he traveled in style, accompanied by two engineers, a doctor, a purser, a draughtsman and twelve chasseurs d’Afrique [12].

Roudaire undertook two expeditions, to the Chott el-Gharsa in 1876 and to the Chott el-Djerid in 1878. The results were mixed, at best: Roudaire was able to establish, at least to the satisfaction of de Lesseps, that the chotts indeed were an ancient seabed. But the Tunisian chotts turned out to be truncated by elevated thresholds. The Chott el-Djerid, which is closest to the sea, was actually situated significantly above sealevel.

Only slightly daunted, Roudaire tried to save his scheme by lengthening his proposed canal while also decreasing the area to be flooded. But it was no use. France’s scientists and engineers turned against the scheme — the former citing bad geography and geology, the latter an estimated cost ballooning to over a billion francs. In 1882, a high commission advised the French government against proceeding with the plan.

But Roudaire and de Lesseps couldn’t help believing in the Sahara Sea. With private money, they founded a Société d’études de la mer intérieure africaine. Under its auspices if no longer the French government’s, Roudaire in early 1883 left Touzeur for a fourth expedition [13]. Even at that palliative stage of the plan, the Boston weekly Littell’s Living Age, still proclaimed: “This is the plan which M. de Lesseps has been engaged in investigating, which Commandant Roudaire has been advocating for some ten years, and which may be said to have a calculable, if not a very immediate, chance of being carried out.”

When Roudaire returned to France, he faced illness and criticism. Both the scientific milieu and his military hierarchy condemned his dogged adherence to what seemed to everyone else a lost cause. The forlorn pioneer of the Sahara Sea died in 1885 at the age of 48, of a fever he brought home from his last expedition.

Roudaine was survived by his African Inland Sea Research Society, which restricted itself to exploring the feasibility of an agricultural colony near Gabès, sinking artesian wells into the sand to fertilise the desert. Lack of results led to the society’s dissolution in 1892.

As visionary as it was impracticable, the idea for a Sahara Sea tickled the fancy of Jules Verne, the grandfather of science fiction. In Hector Servadac (1877; a.k.a. Off on a Comet) he refers to Roudaire’s scheme as if it is actually taking shape. In his last adventure novel, L’Invasion de la mer (1905; a.k.a. The Invasion of the Sea), he revisits the plan, with Berbers and Europeans fighting over the plan, only to have an earthquake create it anyway.

Verne revisited the idea of a Sahara Sea in his last book.

But grand visions never die, they just wait for the next visionary. In 1919, the Roudaire plan was cited as the inspiration for schemes to insert canals deep into the Tunisian interior. As late as 1958, French scientists were proposing versions of the plan. Even today, some suggest Roudaire’s vision could still be realised. No canal required: by pumping water into the Chott El-Djerid, a submarine area west of Gabès of about 8,000 km2. The justification is the same as Roudaire’s: creating an evaporation surface of such size would increase rain in the area, enhancing agricultural opportunities.

But perhaps ancient curses outweigh modern ideas of progress (or simply outlive them). The same legend mentioned above has it that the locals, when hearing Triton’s prediction of a hundred Greek towns crowding around their lake, grabbed a hold of his magic tripod, and hid it in a place safe from the descendants of the Argonauts.

The Sahara Sea not only claimed the life of François Élie Roudaire, it also seems to have tainted the further career of Ferdinand de Lesseps. His later attempt to dig the Panama Canal [14] ended in a gigantic failure and a bribery scandal – for which he received a prison sentence in 1893. It was only commuted because of his advanced age. He died a year later.

The Sahara Sea remains what it was when Roudaire first conceived it: a desert mirage, shimmering in the untouchable distance. Unless and until someone finds Triton’s tripod…

Many thanks to Warren, who sent in this story, found here at ion9.

Strange Maps #617

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] Nor was the Suez Canal an original idea by de Lesseps. In 1832, while in quarantine on board a French mailboat off Alexandria, he came across a feasibility study into the subject, produced by Jacques-Marie Le Père, the director of Bridges and Roads on Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign (1798-1801). Le Père’s Mémoire sur la communication de la mer des Indes à la Méditerranée par la mer Rouge et l’isthme de Soueys had been published in Paris in 1822. ↩

[2] Whether Algeria was a ‘colony’ or simply a part of France depends on how charitable a view you hold of France’s dominion over the country. Th French conquered Algeria in 1830 and annexed it in 1848, at which time its coastal zone was divided into three departments. These were considered a part of France just as much as any other ‘metropolitan’ department, although the native Algerians were granted considerably less rights than other French citizens – about 1 million of which had colonised the coastal districts by the middle of the 20th century. ↩

[3] ‘Chott’ is the French spelling for an Arab word meaning ‘bank’ or ‘coast’, and is pronounced shot. The word describes salt lakes in the northern Sahara across Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia that receive some water in wintertime, but are dry most of the year. ↩

[4] At -40 metres (-130 ft), the area holds the distinction of being Algeria’s lowest point. ↩

[5] Triton is not a place but a person, or rather a god. The son of Poseidon, Triton is a merman (upper body of a man, the tail of a fish) who in the story of the Argonauts dwells on the coast of Libya, where the Argo is cast into Tritonis palus, a marshy lake out of which the god himself has to guide Jason and his crew. ↩

[6] Literally, ‘civilising mission’. The idea was not just to govern colonised people, but to assimilate them into European culture by having them adopt the French language, French culture and dress, and the Christian religion. ↩

[7] The French idea to link Algiers and Abidjan by rail rivalled the British scheme for a Cape-to-Cairo railway; neither proposal would come to fruition. ↩

[8] Small change compared to the 430 million francs it cost to dig the Suez Canal. ↩

[9] ‘Our Sea’ in Latin, a term used by the Romans, first for the eastern Mediterranean, then for the entire sea, as their empire expanded its control over its shores in the first century BC. The term was resurrected by Italian nationalists in the late 19th and by Italian fascists in the early 20th century. For more on Italy’s colonial ambitions under Mussolini, see #325. ↩

[10] Elsewhere, Roudaire cleverly draws analogy to de Lesseps’ achievement by comparing his inland sea (and its projected rate of evaporation) to the Bitter Lakes, bodies of water that were created specifically for the Suez Canal. Although much smaller, they are positioned at a similar latitude (near the 34th parallel north). ↩

[11] An eastern extension of the Saharan Atlas range, situated in northeastern Algeria. Because of its inaccessibility, it remains relatively underdeveloped and retains its Berber character. The Aurès range was where Berbers in 1954 started the rebellion that would morph into the Algerian War of Independence. left Algeria in 1962. ↩

[12] Light infantry corps recruited mainly from the European settlers in North Africa (the so-called ‘pieds-noirs’), as opposed to the Spahis, which were raised from the native North African population. The Chasseurs d’Af distinguished themselves in the Crimean War, ‘s invasion of Mexico, and both World Wars, among other conflicts. They corps were disbanded after Algerian independence, but a (mechanised) successor regiment was reinstated in 1998. ↩

[13] In that year, de Lesseps visited the chotts himself, reporting that the canal in his estimate would cost five years’ work and cost 150 million francs. ↩

[14] In 1904, the Americans would pick up where de Lesseps had left off. See also #188. ↩