East and West Dakota? Here’s What Those States Would Look Like

National Geographic, some years ago: a melancholy piece about the emptying of the Dakotan prairie, illustrated with pictures of pension-age waitresses in doomed diners in dying towns, and of the wind playing with dolls in windowless farmhouses, abandoned long ago.

Same location, same magazine, some months ago. Quite a different picture. Boomtowns brimming with leather-necked oil workers and truck drivers on double shifts; roads, housing and other local infrastructure straining to keep up with an industry eager to frack [1] the fruck out of the shale oil and gas hidden deep in the Dakotan underground.

Dakota fading and Dakota booming: two competing images of one and the same place, the latter erasing the former.

Perhaps the most instantly recognisable vista in either of the Dakotas are the gigantic, rock portraits of four presidents [2], carved out of Mount Rushmore. The iconic attraction which draws in 3 million visitors per year is often regarded as yet another affront to Native American sensibilities. Its companion piece – or antithesis – is a giant rock portrait of the legendary Lakota warrior Crazy Horse, under construction at a site some 20 miles away.

Dakota triumphant and Dakota defiant: again, two rivalling visions, both hewn out of the living rock.

It’s as if the Dakotas are predestined to duality, and not just because of their almost interchangeable names, shapes and sizes [3]. North and South Dakota are one of only three pairs of states [4] named as geographic variants of each other, but of that trifecta, the Dakotan split somehow seems more arbitrary.

In part, perhaps, because it is the most recent: the Dakota Territory, established as the northwest corner of the land acquired from France in the Louisiana Purchase [5], was originally much larger than the area of the two present Dakotas. It had shrunk to their present size by 1868, and was divided in two – by a straight line just below the 46th parallel north – only when North and South Dakota entered the Union in 1889. Dakota entered as two separate states rather than a single one as a Republican ploy to bolster their numbers in the United States Senate [6].

The territory was sliced north-south rather than east-west because of what could be called ‘latitudinal resentment’ between north and south over the location of the territorial capital. In 1861, that epithet had been granted to Yankton, in the southeastern corner of the Dakota Territory. But in 1883, the territorial capital moved to Bismarck [7], in the north. This created enough tension between northern and southern Dakotans to facilitate a split along those lines. Bismarck retained its capital status as seat of government of North Dakota. But Yankton lost out to Pierre, which was chosen as capital of South Dakota precisely because of its proximity to the geographical centre of the new state.

Lurking beneath the surface of what on the face of the map looks like a perfectly non-suspect pair of cartographic personae is an intriguing allohistorical [8] question: What is the Dakota Split had never happened? Or: What if it had happened differently?

Some clearly wish the Dakotas had remained a single state – if only to siphon off some of the $2 billion oil boom surplus money in North Dakota’s state treasury in a southerly direction. Re-union would cost the Dakotans two Senators, but it would gain them an elevated status within the United States. With 1.5 million inhabitants and an area of 148,000 sq. mi, Greater Dakota would be the 40th most populous state, and the 4th largest in area.

But there is another way to crumble the cookie: re-divide the Dakotas, in an eastern and western state. Makes more sense, says Shebby Lee: both halves of the former territory are divided by a natural barrier: the Missouri River, which enters both Dakotas in the northwest, then snakes across the territory, leaving it in the southeast [9]. Here the Missouri sets the precedent, by forming the eastern part of the border between South Dakota and Nebraska [10].

Ms. Lee organises tours of both reconstituted halves of the Dakotas, scheduling visits to Mount Rushmore, the Badlands, Deadwood and Custer State Park on the ‘West Dakota’ trip, and “provid[ing] perspective into the common geographic, economic and psychological characteristics of [West Dakota]”. A similar tour is available for East Dakota.

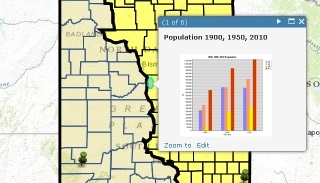

Shebby Lee is not alone in her Dakotan Re-Distributionalism. The locals apparently define each other as ‘East River’ and ‘West River’, based on the place of origin vis-a-vis the Missouri River. Joseph Kerski created this map of ‘ED’ and ‘WD’, based largely on the course of the Missouri. One ironic consequence of the re-arrangement is that Bismarck, once so central in ND, is now a border town. While it is still in East Dakota, its suburb Mandan, across the river, is in West Dakota. Another irony: Bismarck’s South Dakotan rival, Pierre, is also located on the eastern bank of the Missouri. Which of both would become the capital of East Dakota? Or would that honour go to a more centrally located city [11]?

Mr. Kerski doesn’t entirely follow the course of the river: “Northwest of Bismarck, where the river turns west, I included the counties in northwestern North Dakota as part of West Dakota. The reason is that I considered that they have more physical and cultural characteristics in common with the west than the east”.

Population-wise, East and West Dakota are more divergent than North and South Dakota. ED has 1.1 million inhabitants, WD barely 400,000. But WD is growing faster than ED, in large part thanks to the oil boom occurring in the northwest of North Dakota.

So – East and West Dakota: a good idea, a bad idea, or just another idea? The jury is out, and will remain out. But at least the map is in…

Many thanks to Jonah Adkins for sending in this map, found here on ESRI, a company which”inspires and enables people to positively impact the future through a deeper, geographic understanding of the changing world around them”. The other ED/WD map found here on Shebby Lee Tours. The map of a unified Dakota found here at Madville Times.

Strange Maps #609

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] Hydraulic fracturing, or ‘fracking’, is a relatively old drilling technique, used in oil and gas exploitation. Fluids are injected to crack subterranean rock formations, making previously inaccessible hydrocarbon reserves recoverable. As more easily accessible resources have been depleted, and drilling technology has improved, fracking is now used in more than half of new hydrocarbon exploitation – among them many of the wells sunk into the so-called Bakken formation under North Dakota. ↩

[2] Left to right: Washington, Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt, Lincoln. Obviously not in chronological order. ↩

[3] North Dakota ranks 19th out of 50 US states for size (70.700 sq. mi; 183,272 km2), and 48th for population (just short of 700,000). South Dakota is 17th for size (77,116 sq. mi; 199,905 km2) and 46th for population (just under 840,000). Both are rectangular and oblong, resembling no other state more than each other (with the possible exception of Kansas, which is also brick-shaped). ↩

[4] The others being the Carolinas (also North and South; originally a single colony, they became separate colonies of the Crown in the 1720s for reasons that are now quite obscure); and Virginia and West Virginia (the latter separated from the former in 1863, as a consequence divided loyalties during the Civil War. Since the secession happened without sanction from Richmond, the remainder of the original state refused to be addressed as East Virginia).↩

[5] In 1803, the US bought the French territory of Louisiane (828,000 sq. mi, or 2.14 million km23) for 15 million dollars, which works out as just under 3 cents per acre. The sale doubled the size of the United States, and enabled further westward expansion. Price-wise, the Alaska Purchase (1867) proved an even better deal, with the US government paying the Russian Empire 7.2 million dollars for 586,412 sq. mi (1.52 million km2), or roughly 2 cents per acre.↩

[6] Each state delegates two Senators to Congress, whereas each state’s number of delegates to the House of Representatives is based on population size. ↩

[7] Originally founded in 1872 as Edwinton, after an engineer of the Northern Pacific Railroad, which ran through the town, the city was renamed Bismarck a year later to attract German immigrants. The move of the Dakotan territorial capital was in no small part the result of political pressure by the Northern Pacific Railroad. ↩

[8] As in: concerned with alternate history. The most famous questions are: What if the South had won the Civil War, and What if the Germans had won the Second World War. ↩

[9] The longer, western part of the border is formed by the 43th parallel north. ↩

[10] The southernmost part of South Dakota is located at the confluence of the Missouri and Big Sioux Rivers, just to the west of Sioux City, Iowa – at a latitude somewhere between those of Marseille, France and Barcelona, Spain. ↩

[11] Perhaps Jamestown, ND? It would right an historic wrong. Jamestown had been earmarked to be the capital of North Dakota, but the citizens of Bismarck raided the city for the state records, ensuring that their city would remain the capital of the state, as it had been of the territory. Mr. Kerski nominates Sioux Falls. For capital of West Dakota, we both nominate Rapid City, SD. A no-brainer: with about 70,000 inhabitants, it is by far the largest city in the new state. ↩