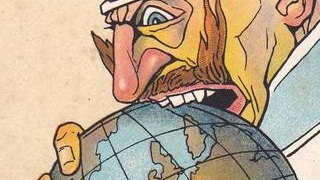

561 – Kaiser Eats World

In a dream-like scene from Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, the titular tyrant [1] gently plucks a large globe from its standalone frame, holds it longingly in his arms and dances it across his office to the tones of Wagner’s Lohengrin.

The globe dance is a variation – arguably one too gentle and dream-like [2] – on a popular theme in cartographic propaganda: the evil genius, hell-bent on world domination, shown grabbing, bestriding, slicing a representation of the planet.

That malevolent mastermind is often symbolised by an octopus, an animal whose sinister tentacularity has made it a staple of map cartoons looking to convey foreign menace [3]. The person depicted here was equally recognisable to the audience of the time (the cartoon dates from 1915, the second year of World War I). Should the black, eagle-encrusted helmet not be clue enough, the trademark handlebar moustache, dispelled any doubt: this is Wilhelm II, the Kaiser [4] of Germany.

Wilhelm II is ferociously trying – but failing – to swallow the world whole. The title L’ingordo is Italian, and translates to: ‘The Glutton’. The subtitle is in French: Trop dur means‘Too hard’. The cartoon, produced by Golia [5], conveys a double message.

It informs the viewer that the current conflict is the result of Wilhelm’s insatiable appetite for war and conquest, but he has bitten off more than he can chew. The image of the Kaiser vainly trying to ingest the world signals both the cause of the Great War, and predicts its outcome – the tyrant shall fail.

No opportunity is missed to portray the Kaiser as an awful monstrosity: the glaring eyes, the sharp teeth, the angrily flaring ends of his upturned moustache [6]. But it must be said that Wilhelm’s portrayal by Allied propaganda as an erratic, war-mongering bully wasn’t entirely unjustified [7]. Upon his accession to the throne in 1888, he personally set Germany on a collision course with other European powers. His impetuous policies were later blamed for reversing the foreign-policy successes of Chancellor Bismarck, whom he dismissed, and ultimately for causing World War I itself.

As Germany’s war effort collapsed in November 1918, Wilhelm abdicated and fled to the Netherlands, which had remained neutral. The Dutch queen Wilhelmina resisted international calls for his extradition and trial. The Kaiser would live out his days in Doorn, not far from Utrecht, spending much of the remaining two decades of his life fuming against the British and the Jews, and hunting and felling trees. He died in 1941, with his host country under Nazi occupation. Contrary to Hitler’s wishes to have him buried in Berlin, Wilhelm was determined not to return to Germany – even in death – unless the monarchy was restored. The gluttonous last Kaiser of Germany, who bit off more than he could chew, is buried at Doorn.

This image found here at Scartists.com.

_______________

[1] Adenoid Hynkel, a thinly veiled parody of Adolf Hitler. The Great Dictator was Chaplin’s indictment of fascism, exposing its “machine heart” to the corrosive power of parody. Curiously, the theme of mistaken identity between the dictator and the Jewish barber (both played by Chaplin) replicates the parallels between Hitler and Chaplin. Both were born only four days apart in April 1889, and both sported similar toothbrush moustaches.

[2] The Great Dictator was very popular upon its release in October 1940; but Chaplin later stated he would never have made it, had he known the extent of the horrors perpetrated by the Nazi regime.

[3] See #521 for an entire post devoted to cartography’s favourite monster.

[4] The German word for Emperor, like the Russian Czar, derives from the Roman Caesar. It retains its particularly negative connotation from World War I, and hence usually applies to Wilhelm II (less to his only predecessor as Emperor of unified Germany, Wilhelm I; or the Emperors of Austro-Hungary).

[5] Italian for ‘Goliath’; pseudonym of the Italian caricaturist, painter and ceramist Eugenio Colmo [1885-1967].

[6] It’s probably no coincidence that they look like flames. Wilhelm II reputedly employed a court barber whose sole function was to give his trademark moustache a daily trim and wax. After his abdication, he grew a beard and let his moustache droop. Perhaps his barber was a republican after all.

[7] In a 1908 interview with the Daily Telegraph, meant to strengthen Anglo-German friendship, Wilhelm called the English “mad, mad, mad as March hares”. Other outbursts in the same interview managed to alienate also the French, Russian and Japanese public opinions. In Germany, the interview led to calls for his abdication; he subsequently lost much of his real domestic power, but came into focus as the target for foreign ridicule.