“Sham Paris”: An Entire City’s Stunt Double

Legend has it that hardly anyone turned up for the opening night of Jean Giraudoux’s (1) play La guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu. Taking the billboards for the play too literally, Parisian theatregoers thought it had been cancelled. True or not, it’s tempting to read this anecdote as a tribute in reverse – even more sublime for being unintended – to the original ruse that ended the Trojan War.

The beleaguered Trojans tricked into hauling that wooden, warrior-filled horse inside their unscalable walls – this is the Odyssean Moment: that seminal turning point in military prehistory, when obfuscation and deception joined high courage and brutal force in the human arsenal of war.

In 1917, the spirit of Odysseus moved the French high command to construct a wooden decoy of their own. But in this case, that decoy wasn’t an instrument to conquer a city. It was the city itself. A false one, to protect the City of (Blacked-Out) Lights nearby. Like a proper stunt double, this false Paris was supposed to take the blows for the real one. It was to be laid out at Maisons-Laffitte, 11 miles (18 km) to the northwest of the actual city centre of Paris, in those pre-radar days considered a distance both safe and credible enough to confuse German war planes aiming for the French capital.

In that early, primitive stage of air warfare, the proto-Luftwaffe’s payload consisted of single, hand-thrown bombs. Almost charmingly artisanal, compared to the industrial-scale carpet bombing of later conflicts, but still considered bloody inconvenient by the French government of the day. The faux Paris was meant to absorb as much of this threat as possible, but never got to fulfil its role: the war ended before it was completed.

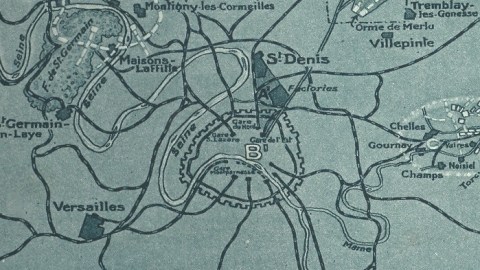

Its near-existence was revealed on 6 November 1920 by the Illustrated London News, under the title A False Paris Outside Paris—a ‘City’ Created to be Bombed. This first map provides an overview of the relevant part of the île de France.

The original legend reads:

[…] a plan for a sham Paris in the forest of St. Germain: the general scheme (party carried out) of false nocturnal objectives. Three zones of false objectives were planned, and one (A2) was actually carried out. The others became unnecessary through the ending of the war. The letters on the above map show: A1, the real district of St. Denis; A2, the sham St. Denis, actually created between Orme de Merlu and Louvres; B1, the real Paris; B2, the the sham Paris which was to have been created between Maisons-Laffitte and Conflans; C, a false factory district planned around Vaires.

The map key shows Existing Railways, Sham Railways and Sham Factories.

A second map zooms in on the area of Maisons-Laffitte, where a bend in the river resembling a similar one in Paris itself is used as the backbone of a ‘Sham Paris’. The capital’s topography was to be transplanted onto the existing villages of Maisons-Laffitte, Sartrouville, Montigny-les-Cormeilles, Herblay, Conflans-Ste-Honorine, Beauchamp and Pierrelaye. The dark lines and contours on this map trace the real towns and roads, the dotted white lines indicate the fake Parisian boulevards, train stations and traffic nodes.

Just north of the river, the radiant layout of the Place de l’Etoile can be made out. Other targets to be carefully copied included the strategically important train termini: the Gare du Nord, and Gare de l’Est, just south of Beauchamp; the Gare St. Lazare, between Beauchamp and Conflans; the Gare de Vincennes and Gare de Lyon, near Montigny; the Gare d’Austerlitz, Gare d’Orsay and Gare des Invalides, skirting the south bank of the river,and the Gare Montparnasse, near the park at Maisons-Laffitte.

The copied layout would have been rendered visible to German pilots by a studied use of lights and luminous canvas. One comparison comes to mind: the Potemkin villages supposedly constructed by the eponymous Russian minister in the Crimea to impress Empress Catherine with the importance of his conquests.

Being an urban myth, those villages share one important trait with this Potemkin Paris: they were never built. And its bombardment has this in common with Giraudoux’s Trojan War: it never took place.

Many thanks to Christophe Girard, Romain Paulus and Hildoceras, who sent in links to these maps, recently reported here at Ptak Science Books, and inordinately interesting blog, cited earlier in Strange Map #497.

Strange Maps #540

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

______________

(1) And not, as first reported, by Jean Anouilh.