When Maine Went to War over its Northern Border

“From the northwest angle of Nova Scotia, to wit, that angle which is formed by a line drawn due north from the source of the St Croix River to the highlands, along the said highlands which divide those rivers that empty themselves into the St Lawrence, and those which fall into the Atlantic Ocean, to the northwestern most head of the Connecticut River…”

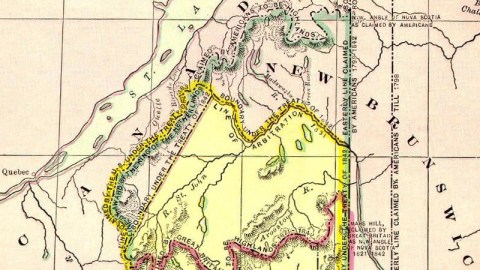

That definition of the border between what were then the District of Maine (a possession of the US State of Massachusetts) and the British colony of New Brunswick was mentioned in the 1783 Treaty of Paris that officialised American independence. The wording of the text proved too vague – especially when that lumber-rich area became coveted by loggers from both sides of the ill-defined border. The dispute heated up after 1820, the year in which Maine gained statehood – before, it had formed a non-contiguous ‘District’ of Massachusetts. Surveyors sent out by the new state to – literally – mark out its territory were surprised to find on both banks of the St John River thriving communities of Acadians. These French-speakers came from further up north, and thus were British subjects.Maine granted land to American settlers in the adjacent Aroostook River valley, leading to disputes in which the King of the Netherlands was asked to arbitrate.

In 1832, the US Senate rejected the border proposed by the Dutch King (although it would have given the US more territory than the eventual settlement of 1842). In 1837, a Maine official conducting a census in the disputed area was arrested by New Brunswick officials. The Maine legislature dispatched a 200-strong force of ‘red shirts’ up north to confront the New Brunswick ‘blue noses’, and the US Congress raised a 10.000-strong militia to support Maine’s cause.

The Americans seized ‘British’ timber to build blockhouses to defend against British intrusion, but no actual fighting ever took place. This frontier version of what was later called a Sitzkrieg (the ‘sitting war’, after the declaration of war but before the actual beginning of hostilities between France and Germany in World War Two) became known as the ‘Aroostook War’, or the ‘Pork and Beans War’, or also the ‘Lumberjack War’ and lasted from 1838 to 1839.

In spite of its many names, the war was completely bloodless. Yet legend has it there was one casualty: either a Canadian pig wandering over the border, or a cow shot by mistake while wandering outside the Fort Kent blockhouse. Or that one casualty might be private Hiram T. Smith, buried in Haynesville (ME) and frequently cited as the ‘only casualty of the Aroostook War’ – a shaky claim, as no one seems to know exactly what he died from.Further casualties were avoided, as in 1839 it was agreed that (US) Congressman Daniel Webster and (British) Lord Ashburton should work out a compromise border.

In 1842, they settled that the US would get over 18.000 sq. km (7.000 sq. mi) of the disputed area, up to the St Johns River, which would be opened up for free navigation by both countries. Great Britain got almost 13.000 sq. km (5.000 sq. mi) of disputed territory, allowing them an overland route between Lower Canada and Nova Scotia that was usable year-round – the Halifax Road.

Other achievements of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty were the fixing of the US-Canada border in the Great Lakes area, and the setting of a peaceful precedent for resolving territorial and other disputes between the US and its northern neighbour.

In its entry on the Aroostook War, Wikipedia has this interesting cartographic bit of trivia: “Webster used a map found in the Paris Archives by the American Jared Sparks (and said to have been marked with a red line by Benjamin Franklin in Paris in 1782) to persuade Maine and Massachusetts to accept the agreement. As the map showed the disputed region belonged to the British, it helped convince the representatives of those states to accept the compromise, lest the “truth” reach British ears and convince the British to refuse a compromise. It was later discovered that the Americans had hidden their knowledge of the Franklin map. A map said to be favorable to the United States claims was apparently used in Britain, but this map was never revealed. Some claim the Franklin map was a fake created by Britain to pressure the American negotiators as their map placed the entire disputed area on the American side of the border.”

Here below is reproduced the ‘Aroostook War Fighting Song’, composed in Bangor in February 1839 to the tune of Auld Lang Syne. For its lyrics, and much of the historical information in the text above aswell as the map reproduced here, I’m much indebted to the website of Scott Michaud, who recounts his Franco-American family’s history in northern Maine.Nowadays, the northernmost county of Maine is still called Aroostook, and still boasts a strong link with its French past. Incidentally, at 17.686 sq. km Aroostook County is the largest US county east of the Mississippi. Two US towns in Aroostook County, right on the St John River across from Canada, were named after American leaders in the ‘war’: Fort Kent (after then Maine governor Edward Kent) and Van Buren (after then president Martin Van Buren).

The Aroostook War Fighting Song

We are marching on to Madawask, To fight the trespassers; We’ll teach the British how to walk And come off conquerors.

We’ll have our land, right good and clear, For all the English say; They shall not cut another log, Nor stay another day.

They need not think to have our land, We Yankees can fight well; We’ve whipped them twice most manfully, As every child can tell.

And if the tyrants say one word, A third time we will show, How high the Yankee spirit runs, And what our guns can do.

They better much all stay at home, And mind their business there; The way we treated them before, Made all the nations stare.

Come on! Brace fellows, one and all! The Red-Coats ne’er shall say, We Yankees, feared to meet them armed, So gave our land away.

We’ll feed them well with ball and shot. We’ll cut these red-coats down, Before we yield to them an inch Or title of our ground.

Ye husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, From every quarter come! March, to the bugle and the fife! March, to the beating drum!

Onward! My lads so brave and true Our country’s right demands With justice, and with glory fight, For these Aroostook lands!

Please also check out Chip Gagnon’s page about this map on the Upper St John River Valley website (aussi en français).

Strange Maps #106

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.