Yes, Virtual Particles Can Have Real, Observable Effects

The nature of our quantum Universe is puzzling, counterintuitive, and testable. The results don’t lie.

Although our intuition is an incredibly useful tool for navigating daily life, developed from a lifetime of experience in our own bodies on Earth, it’s often horrid for providing guidance outside of that realm. On scales of both the very large and the very small, we do far better by applying our best scientific theories, extracting physical predictions, and then observing and measuring the critical phenomena.

Without this approach, we never would have come to understood the basic building blocks of matter, the relativistic behavior of matter and energy, or the fundamental nature of space and time themselves. But nothing matches the counterintuitive nature of quantum vacuum. Empty space isn’t completely empty, but consists of an indeterminate state of fluctuating fields and particles. It’s not science fiction; it’s a theoretical framework with testable, observable predictions. 80 years after Heisenberg first postulated an observational test, humanity has confirmed it. Here’s what we’ve learned.

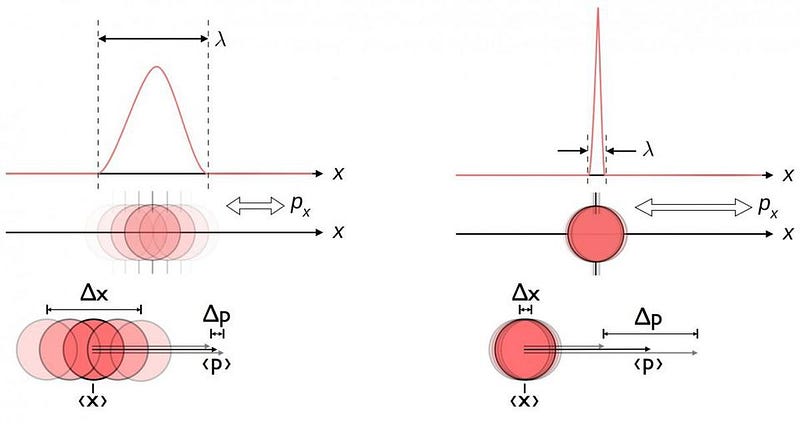

Discovering that our Universe was quantum in nature brought with it a lot of unintuitive consequences. The better you measured a particle’s position, the more fundamentally indeterminate its momentum was. The shorter an unstable particle lived, the less well-known its mass fundamentally was. Material objects that appear to be solid on macroscopic scales can exhibit wave-like properties under the right experimental conditions.

But empty space holds perhaps the top spot when it comes to a phenomenon that defies our intuition. Even if you remove all the particles and radiation from a region of space — i.e., all the sources of quantum fields — space still won’t be empty. It will consist of virtual pairs of particles and antiparticles, whose existence and energy spectra can be calculated. Sending the right physical signal through that empty space should have consequences that are observable.

The particles that temporarily exist in the quantum vacuum themselves might be virtual, but their effect on matter or radiation is very real. When you have a region of space that particles pass through, the properties of that space can very much have real, physical effects that be predicted and tested.

One of those effects is this: when light propagates through a vacuum, if space is perfectly empty, it should move through that space unimpeded: without bending, slowing, or breaking into multiple wavelengths. Applying an external magnetic field doesn’t change this, as photons, with their oscillatory electric and magnetic fields, don’t bend in a magnetic field. Even when your space is filled with particle/antiparticle pairs, this effect doesn’t change. But if you apply a strong magnetic field to a space filled with particle/antiparticle pairs, suddenly a real, observable effect arises.

When you have particle/antiparticle pairs present in empty space, you might think they simply pop into existence, live for a little while, and then re-annihilate and go back into nothingness. In empty space with no external fields, this is true: Heisenberg’s energy-time uncertainty principle applies, and so long as all the relevant conservation laws are still obeyed, this is all that happens.

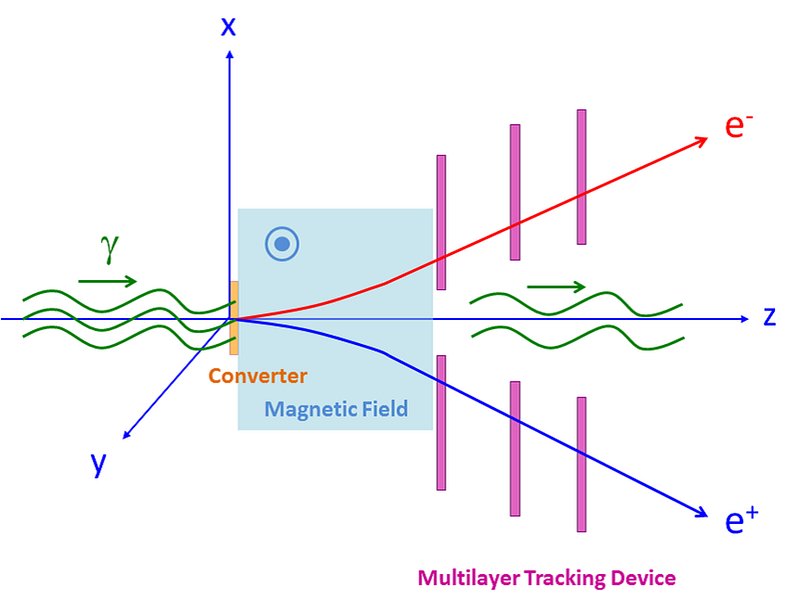

But when you apply a strong magnetic field, particles and antiparticles have opposite charges from one another. Particles with the same velocities but opposite charges will bend in opposite directions in the presence of a magnetic field, and light that passes through a region of space with charged particles that move in this particular fashion should exhibit an effect: it should get polarized. If the magnetic field is strong enough, this should lead to an observably large polarization, by an amount that’s dependent on the strength of the magnetic field.

This effect is known as vacuum birefringence, occurring when charged particles get yanked in opposite directions by strong magnetic field lines. Even in the absence of particles, the magnetic field will induce this effect on the quantum vacuum (i.e., empty space) alone. The effect of this vacuum birefringence gets stronger very quickly as the magnetic field strength increases: as the square of the field strength. Even though the effect is small, we have places in the Universe where the magnetic field strengths get large enough to make these effects relevant.

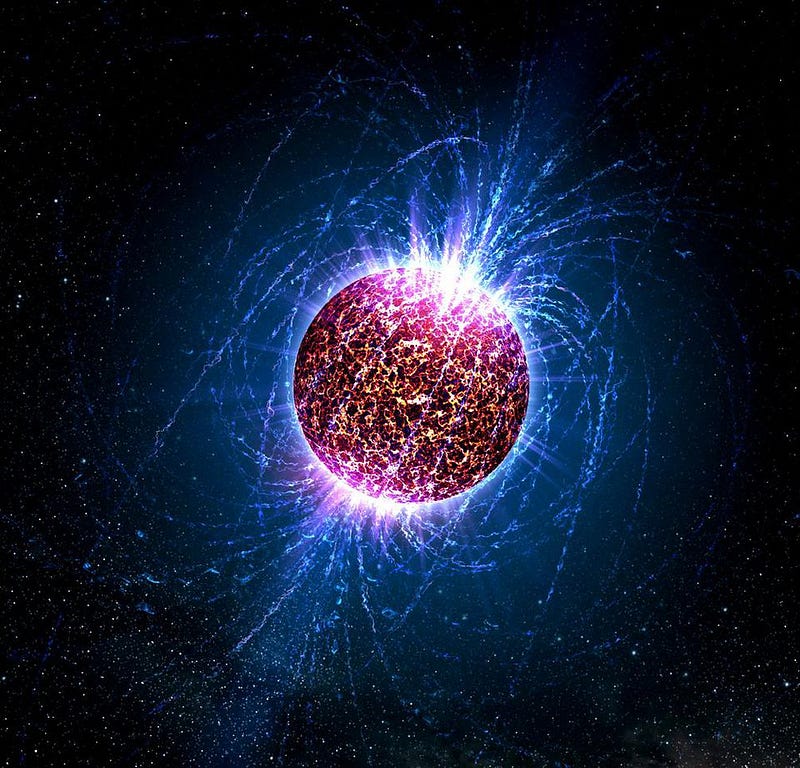

Earth’s natural magnetic field might only be ~100 microtesla, and the strongest human-made fields are still only about 100 T. But neutron stars give us the opportunity for particularly extreme conditions, giving us large volumes of space where the field strength exceeds 10⁸ (100 million) T, ideal conditions for measuring vacuum birefringence.

How do neutron stars make such large magnetic fields? The answer may not be what you think. Although it might be tempting to take the name ‘neutron star’ quite literally, it isn’t made exclusively out of neutrons. The outer 10% of a neutron star consists mostly of protons, light nuclei, and electrons, which can stably exist without being crushed at the neutron star’s surface.

Neutron stars rotate extremely rapidly, frequently in excess of 10% the speed of light, meaning that these charged particles on the outskirts of the neutron star are always in motion, which necessitated the production of both electric currents and induced magnetic fields. These are the fields we should be looking for if we want to observe vacuum birefringence, and its effect on the polarization of light.

It’s a challenge to measure the light from neutron stars: although they’re quite hot, hotter even than normal stars, they’re tiny, with diameters of just a few dozen kilometers. A neutron star is like a glowing Sun-like star, at perhaps two or three times the temperature of the Sun, compressed into a volume the size of Washington, D.C.

Neutron stars are very faint, but they do emit light from all across the spectrum, including all the way down into the radio part of the spectrum. Depending on where we choose to look, we can observe the wavelength-dependent effects that the effect of vacuum birefringence has on the light’s polarization.

All of the light that’s emitted must pass through the strong magnetic field around the neutron star on its way to our eyes, telescopes, and detectors. If the magnetized space that it passes through exhibits the expected vacuum birefringence effect, that light should all be polarized, with a common direction of polarization for all the photons.

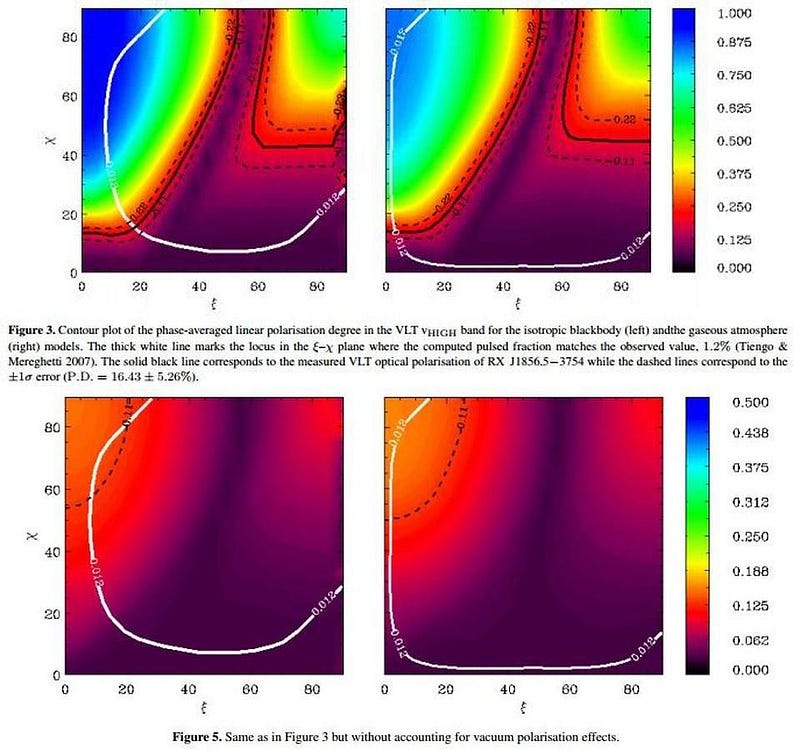

In 2016, scientists were able to locate a neutron star that was close enough and possessed a strong enough magnetic field to make these observations possible. Working with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, which can take fantastic optical and infrared observations, including polarization, a team led by Roberto Mignani was able to measure the polarization effect from the neutron star RX J1856.5–3754.

The authors were able to extract, from the data, a large effect: a polarization degree of around 15%. They also calculated what the theoretical effect from vacuum birefringence ought to be, and subtracted it out from the actual, measured data. What they found was spectacular: the theoretical effect of vacuum birefringence accounted for practically all of the observed polarization. In other words, the data and the predictions matched almost perfectly.

You might think that a closer, younger pulsar (like the one in the Crab Nebula) might be better suited to making such a measurement, but there’s a reason that RX J1856.5–3754 is special: its surface is not obscured by a dense, plasma-filled magnetosphere.

If you watch a pulsar like the one in the Crab Nebula, you can see the effects of opacity in the region surrounding it; it’s simply not transparent to the light we’d want to measure.

But the light around RX J1856.5–3754 is just perfect. With the polarization measurements in this portion of the electromagnetic spectrum from this pulsar, we have confirmation that light is, in fact, polarized in the same direction as the predictions arising from vacuum birefringence in quantum electrodynamics. This is the confirmation of an effect predicted so long ago — in 1936 — by Werner Heisenberg and Hans Euler that, decades after the death of both men, we can now add “theoretical astrophysicist” to each of their resumes.

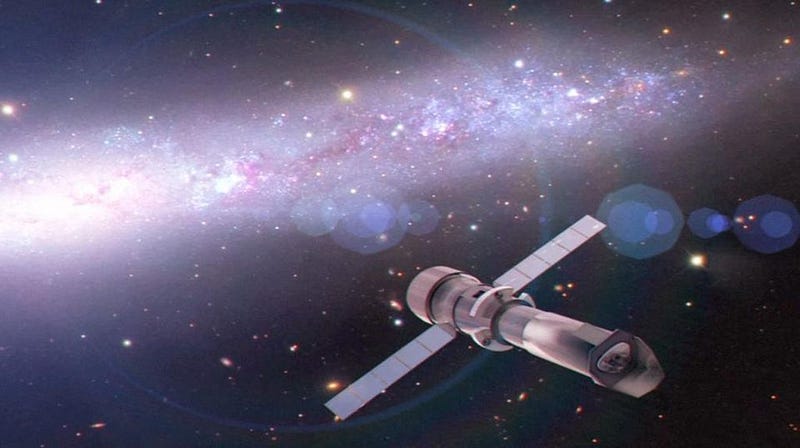

Now that the effect of vacuum birefringence has been observed — and by association, the physical impact of the virtual particles in the quantum vacuum — we can attempt to confirm it even further with more precise quantitative measurements. The way to do that is to measure RX J1856.5–3754 in the X-rays, and measuring the polarization of X-ray light.

While we don’t have a space telescope capable of measuring X-ray polarization right now, one of them is in the works: the ESA’s Athena mission. Unlike the ~15% polarization observed by the VLT in the wavelengths it probes, X-rays should be fully polarized, displaying right around an 100% effect. Athena is currently slated for launch in 2028, and could deliver this confirmation for not just one but many neutron stars. It’s another victory for the unintuitive, but undeniably fascinating, quantum Universe.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.