What Really Kept American Women From Going To Space For So Long?

A fascinating new book tells the untold stories of two women, Jackie Cochran and Jerrie Cobb, who could have been first.

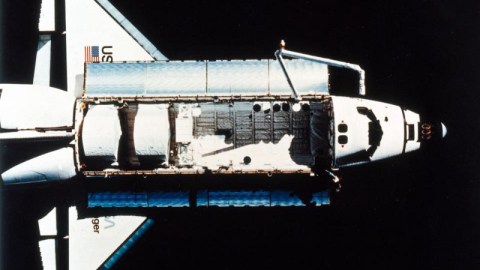

On June 18, 1983, the Space Shuttle Challenger launched with a crew of five persons aboard, including Sally Ride, who on that date became the first American woman to leave Earth and enter space. But for a generation of women who strove for — and were denied — the opportunity to become astronauts back during the space race of the 1950s and 1960s, it was a bittersweet moment. A momentous leap forward may have occurred, but the pilots who bravely advocated for women in spaceflight never got to take that leap themselves.

In an incredibly well-researched new book, Fighting For Space: Two Pilots and Their Historic Battle For Female Spaceflight, space historian Amy Shira Teitel recounts the early days of spaceflight through the lives of arguably the two most qualified women pilots of the mid-20th century: Jackie Cochran and Jerrie Cobb. Their stories are simultaneously flawed and sympathetic, and that’s part of what makes it such a fascinating read.

When you think about the most famous pilots in aviation history, names like Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, and Chuck Yeager immediately spring to mind. But Jackie Cochran was easily on par with any of them. She held more speed, altitude, and distance records than any other pilot in aviation history, regardless of gender.

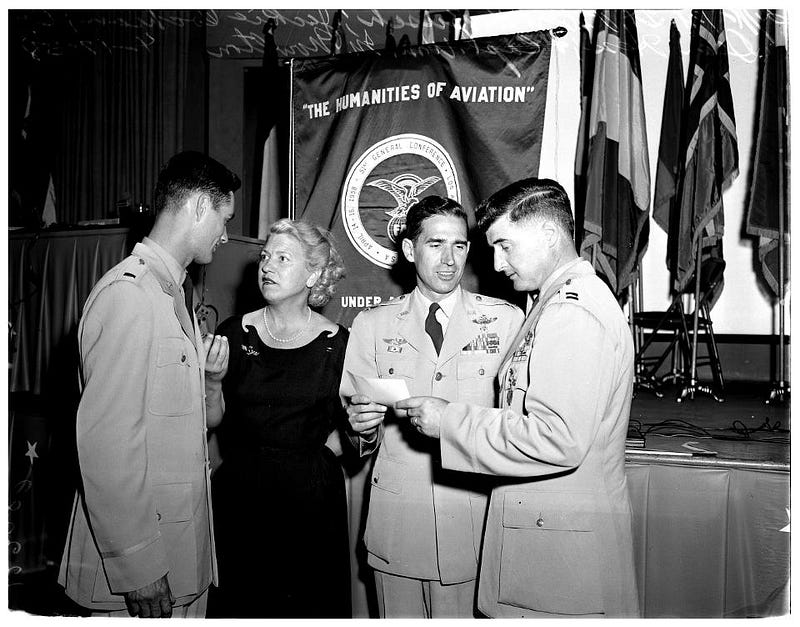

She was an incredibly fast learner who out-worked everyone else around her in all aspects of life, from flight (where she earned her pilot’s license in just 3 weeks) to business (where she started her own very successful cosmetics company) to air racing (where she set an enormous number of records and won presitigous trophies and races) to military service (where she directed the WASPs during WWII) and more. In 1953, she became the first woman to break the sound barrier.

Jackie Cochran’s story is nothing short of remarkable. She came from nothing, taking on a new identity from a very young age to forge her own path in the world. She often took enormous risks, bluffing her way to the top of whatever endeavor she pursued, unflagging in her self-confidence and ability to live up to whatever lofty promises she would make, backing them up more often than not.

She was relentless in all of her pursuits, from love to power to wealth to politics. She married one of the wealthiest men in America; she built friendships with Lyndon Johnson and Dwight Eisenhower (possibly helping save LBJ’s life at one point); she became excellent friends with Amelia Earhart and was mentored by Chuck Yeager. She even, herself, ran for Congress, almost winning a seat. And in the late 1950s, she became active in the early days of the space race, where she helped oversee a program to test women for fitness for spaceflight.

A generation younger, Jerrie Cobb’s life began humbly in rural Oklahoma, where her childhood encounters with airplanes would pave the way to a pilot’s life for her. Jerrie had none of the wealth or power of Jackie, but much like Jackie, would approach whatever goal she set for herself with single-minded commitment. Throughout much of her early adulthood, that goal was relatively simple: to find a flying job.

But as a woman in post-WWII America, no one wanted to hire her. No matter how much competence she displayed or how much she achieved — from race victories to flight endurance to successful missions with inferior or malfunctioning equipment — she couldn’t find anyone to give her steady work. Despite thousands upon thousands of hours flying, despite setting altitude records in propeller-driven planes, despite her success whenever she was given a chance, few people stepped up to champion Jerrie Cobb.

So when Cobb — who was by then one of the pre-eminent women in aviation in America — found out about the early astronaut selection process, she asked herself the question that so many marginalized people throughout history have asked themselves: “why not me?” Feeling the pull of outer space, which drew her ever since she first flew high enough to see the stars during the day, Cobb embarked on a quest that would consume her life for the next 5 years: a quest to become the first woman in space.

Leveraging every resource at her disposal, Cobb went to everyone she could think of to support her, including professionals in aviation medicine, journalists, politicians, members of NASA, and other potential astronauts, both men and women. It’s a fascinating story, one that’s largely gone untold until now, about a hero’s (or heroine’s) quest whose outcome was never in doubt, and yet you can’t help but cheer for Cobb, the unrelenting underdog.

The biographical aspects of the story are meticulously researched, and simultaneously portray how both of the protagonists, Jackie Cochran and Jerrie Cobb, were each remarkable individuals in their own right and yet complex at the same time. Jackie achieved more, in many ways, than any woman that came before her, and helped pave the way for the eventual first woman astronauts. Yet she never went to bat for any of the junior women aspiring to be astronauts, selling out Cobb in particular at the most crucial moments.

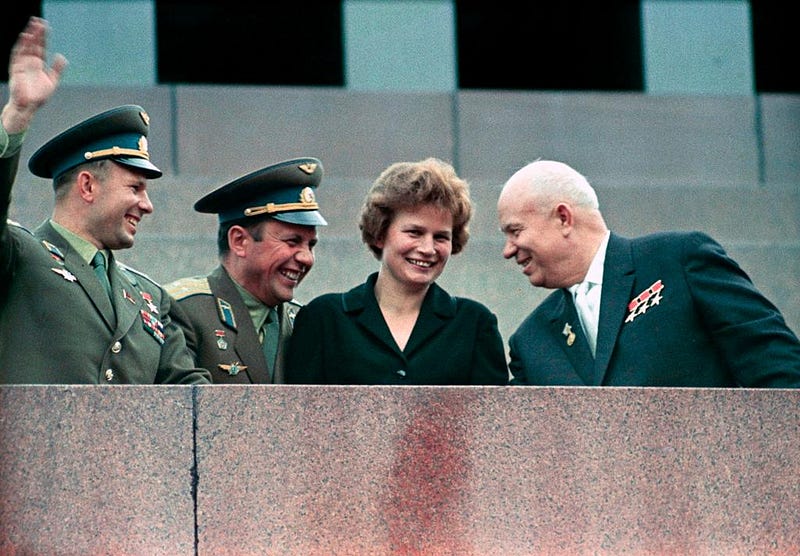

Cobb, meanwhile, used every trick in the book she could muster to obtain a congressional hearing about the fitness for women in space, but had no idea that Lyndon Johnson and Jim Webb — the Vice-President and the head of NASA at the time — had already decided to punt on the issue of women in space until after the Space Race was concluded. The ruckus that Cobb raised may have directly led to the flight of Valentina Tereshkova, who became the first woman in space for the Soviet Union in 1963.

The lead-up to the congressional hearing in July of 1962 — which itself serves as the climax of the story — contains a number of cringe-worthy moments in terms of sexism. From people at NASA who literally and openly stated their preference for women “barefoot and pregnant” to one of the women pilots who underwent testing flying home to divorce papers due to an insecure husband, much of the overt gender discrimination is as horrifying as it is common.

But what’s perhaps most breathtaking about the book is the sheer number of long-buried letters and correspondences that Teitel has unearthed and reproduced in full. We get a window into the minds of major players in the story, including not only Cochran and Cobb, but Lyndon Johnson, Jim Webb, Janey Hart (another woman pilot who underwent testing and supported Cobb and women astronauts), John Glenn and many more.

If you come to this book without any knowledge of the nascent days of spaceflight, Teitel’s writing will immediately immerse you in this foreign landscape, making you feel like you’re experiencing the personal journeys of these remarkable characters right alongside them. If you do have a knowledge of many of the events, her writing will likely only deepen whatever your opinion was going into the story.

If you view 1950s/1960s NASA as an organization focused to putting men on the Moon and unwilling to take any detours from that, you’ll find that story. If you view it as an organization complicit in sexist practices, you’ll find that, too. If you view Cobb as a capable pilot who never got her chance, you’ll find that; if you view her as a pushy, entitled woman, you’ll find that, too. I came into this story knowing about the author (Teitel) and her excellent writings and videos on space history as well as Jerrie Cobb, but Jackie Cochran was new to me, and left me with incredibly conflicted feelings, particularly in light of one specific letter she wrote on March 23, 1962.

Writing to Jerrie Cobb with the goal of preserving the slow, steady progress that Cochran herself had spearheaded, she laid out all the reasons why Cobb should stop causing such a ruckus. Why she should accept Cochran’s lead and fall into line; why the goal of putting women in space wasn’t of national importance; why Cobb and the other women who were hoping to be astronauts should be indebted to her and know their place, and so on.

In every way, at least to me, it was one of the purest incarnations of the ultimate sexist cliché: a woman who had achieved more than any woman in her field before her supporting all of the junior women right up until the critical point where one (or more) of them threatened to surpass her. The greatest tragedy in all of this is that an elite person did everything she could to prove herself, and did so at every turn, but was never afforded the opportunity to excel or fail based on her own merits where it mattered most.

Indeed, the only astronaut qualification that Cobb lacked was that of a jet test pilot, which was an avenue closed to women at the time. Despite the fact that exceptions were made for male astronauts who lacked necessary qualifications, such as Deke Slayton and John Glenn, no women were given the opportunity to become astronauts until NASA Astronaut Group 8 was selected in 1978.

Cobb repeatedly sought opportunities throughout her later life to travel to space, including in 1998, where she mounted a failed campaign to convince NASA to send up not just John Glenn to study the effects of spaceflight on senior citizens, but a woman — herself — as well. Depending on who you are, your conclusion about who’s a hero, who’s a villain, and who was right or wrong will vary. But no matter what, Teitel’s Fighting For Space is a great read about the first attempt to put women in space, and the women who almost made it happen 20 years before it actually did.

The author acknowledges that he received a free advance copy of the book from Grand Central Publishing.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.