Weekend Diversion: The NFL Story You Don’t Hear

It’s all too common to hear about the violent crimes of NFL players. But that’s not the full story.

“I can look in their eyes and see it. That’s the best feeling I can have. … I know I didn’t affect their lives just today, but it carries on for years and years to come.” –Warrick Dunn

It’s easy — way too easy — to look at someone who doesn’t meet your expectations of what someone in their role ought to look like or how they ought to behave, and judge them harshly. If someone comes along in one of these spheres and you’re not a fan of theirs, it’s almost more common than not to do so. We have all sorts of words for the actor, athlete or musician who doesn’t look, speak or behave the way we’d like: thug, gangster, criminal, etc. Have a listen to Uncle Tupelo’s song, Criminals,

while you consider the off-the-field headlines you might have heard about the NFL — the National Football League (for you non-Americans) — over the past few years:

- star running back disciplines his four year old son by savagely beatuing him with a stick and sending him to the hospital,

- star running back beats his wife in a hotel elevator, knocking her out cold and having the video go viral,

- star defensive player found with an arsenal of illegal guns,

- or most egregiously, star tight end guilty of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

There have been all sorts of theories as to why these crime are so common in the NFL among its players, with some purporting that this violent sport encourages violence. Others contend that many of the NFL’s stars grew up in crime-riddled areas, and they bring what they know with them wherever they go. Still others contend that there’s a culture in the locker room that brings out the worst in these men, and that the whole enterprise only turns them into animals.

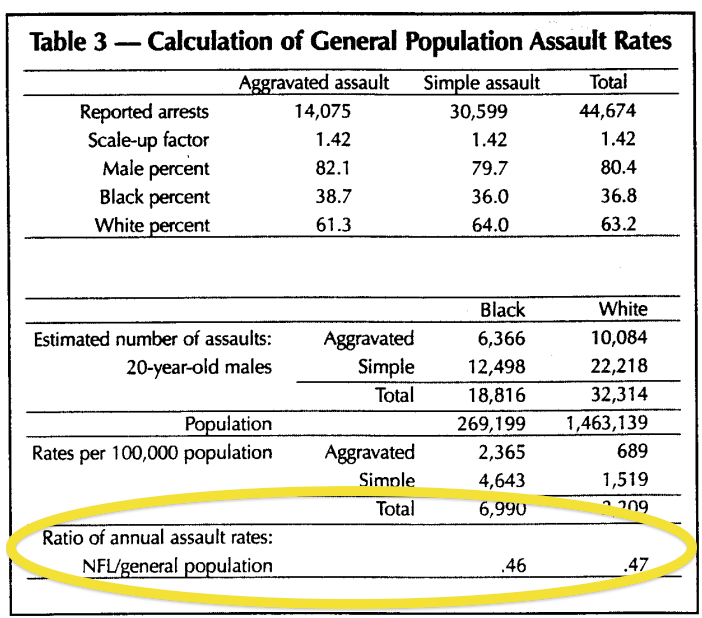

But not only are those “theories” merely conjectures, there isn’t even evidence that violence or crime among NFL players is more prevalent than elsewhere. In fact, two separate studies just came out, comparing the crime rate of men aged 20–39 in the general population with the crime rate of NFL players during the past 13–15 years or so.

The results? NFL players have lower crime and arrest rates across all metrics than the general population, including assault, domestic violence, homicide, rape, DUI, drugs and many others. In fact, when you look at the aggregate rates of all players versus the general population, their arrest rates are less than half of the average non-NFL player.

It seems very, very unfair, then, that those stories — of crimes committed by NFL players — are reported so disproportionately, and that the players are stigmatized in general as having something wrong with them.

Especially when there are many of them doing absolutely great things that don’t get highlighted. So in order to flip the script, I’d like to introduce you to someone that those of you who’ve lived in Florida or Georgia (or die-hard NFL fans) may remember quite fondly: Warrick Dunn.

Warrick Dunn, for those who don’t know, was a star running back with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the Atlanta Falcons from the late 1990s-2000s. He was good enough as a player that he’ll be considered for the Hall of Fame over the next few years, but I had the good fortune to move to Florida in 2001 (for graduate school), and quickly became acquainted with what Warrick Dunn was doing off-the-field.

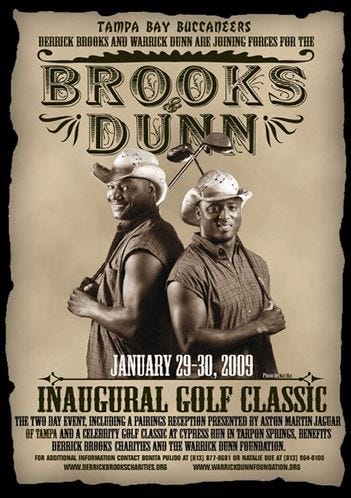

Dunn went to college in Florida (at Florida State), and as soon as he broke into the NFL, he started the Warrick Dunn Family Foundation. Along with his teammate, Derrick Brooks, he would put on an annual charity event (cleverly called “Brooks & Dunn”) to help underprivileged children and families.

After retiring in 2009, Dunn quietly continued his charity work. What most people don’t know is where the Warrick Dunn Family Foundation comes from, and what it’s all about. It’s a story that’s worth telling.

When he was 18, Warrick Dunn’s single mom, a police officer and security guard, was killed in the line of duty, murdered during an armed robbery. As the oldest of six children, Dunn considered quitting college and quitting football to provide for his brothers and sisters, but his community (he was from Baton Rouge) vowed to look after his siblings while he attended (and played football for) Florida State. He vowed that to say thanks, if he ever had the means, he would not only take care of his own family, but as many families in need as he could.

What that means — when he says help families in need — is that he provides homes for them. Nice ones, for their whole family no matter what its size is, and no matter what their needs are. They provide homes with everything in it. Since he first started providing homes, he’s kept track of everyone and how their lives have been touched.

Home 144 @WDCharities, Hurricane Sandy family. Thank you @habitatmonmouth & the Debartolo Family Foundation pic.twitter.com/VylFavqrQS

— Warrick Dunn (@WarrickDunn) September 2, 2015

As of right now, he’s donated a whopping 145 homes to families, averaging about one per month. And he has a very, very reachable goal for the end of the year: he wants to get to 150 by the end of the year.

Heard about my #28challenge? Jump in, http://t.co/1Lk60SjY1X. S/O to donors! Help us reach 150 families by Spring. pic.twitter.com/jAYnlfXrB8

— Warrick Dunn (@WarrickDunn) October 7, 2015

Some of you have asked me if you can donate toward my efforts to keep up with all the science writing and communication I do, but don’t feel comfortable using Patreon for whatever reasons you may have. While I appreciate the sentiment greatly, the Warrick Dunn Family Foundation is a charity that’s captured my heart, and if you wanted to do something good, you can become one of the 28,000 people they’re hoping donate $28 over a span of 28 days: the 28 Challenge. (Dunn was #28, if you were wondering.)

So next time you think of the NFL, don’t just think about the cold, hard facts that its players are better citizens than the typical members of the USA, but also think of the tremendous good that some of its greatest ambassadors have brought to this world. And if you have the means and the inclination, help them bring a little bit more.

Missed the best of our comments of the past week? Check them out here, and don’t forget to leave your comments at our forum and support the 28 Challenge.