Throwback Thursday: Stop Sexism in Science

Whether or not you believe there’s a problem, we’re all part of the solution.

“Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing.” –John Stuart Mill

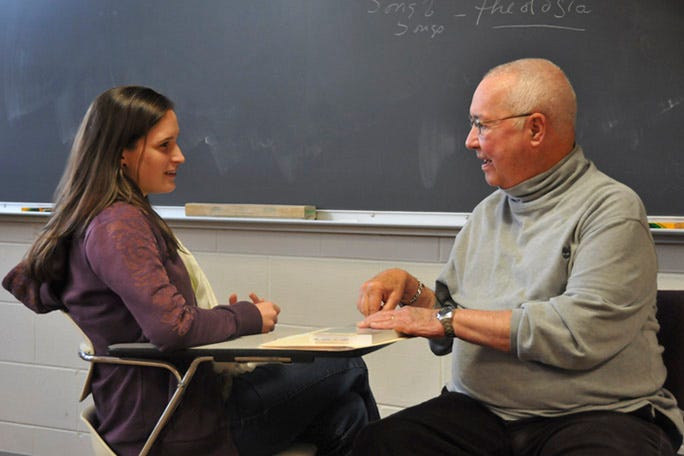

No one becomes a master overnight, and practically no one does it without the outside help and support of not just a mentor, but of a number of peers, advisors and other allies along the way. For those of you who’re on your way towards becoming an expert in a science or technology field, that’s very much what your experience has likely been so far, and what you’re headed for a lot more of as you continue down your path. You rarely become an expert in isolation, but rather by working closely with a diversity of people who know more than you (and can teach you new things), less than you (and can give you the practice of teaching, yourself, ways to experience your knowledge in new ways and settings), and equal-but-complementary things to you.

At least, that was my story, as well as the story of pretty much everyone I knew as I went through first my undergraduate, and then my graduate and postdoc (and professorial) education.

I remember being an undergraduate. (And now, I get to experience a whole slew of them, anew, as a professor.) I remember the combined struggles of rigorous academics, self-confidence crises, trying to figure myself out as a person, and trying to make friends and forge relationships all at the same time. It was my first foray into the beginnings of adulthood, and I remember being thankful for a number of things.

That there was a group of my peers who I’d work with as we struggled through the problems.

That I had a large number of quality professors and teaching assistants who’d take the time to explain what they knew in a variety of ways.

And that there were a number of professors that I trusted to advise me — both academic and in terms of life lessons — to the best of their knowledge and ability. Whether a professor gave me a good grade, a bad grade, praise or criticism, a recommendation or a refusal, I took for granted that it was based on, if not my actual merits in every case, at least their perception of my merits. I didn’t think about it too much at the time, but not once did I ever have to worry that any one of them was spending their time and effort with me trying to get something from me, or evaluating me on something other than my own merits (or lack thereof).

But I was aware that others did have to not only worry — but face — exactly those other things. The professor who leaned in just a little too-close-for-comfort, not to everyone, but to one girl in particular. The student invited to an academic event one evening, only to find out that her lecturer viewed it as a date. And the one professor who always looked me (and the other young men) right in the eye when we spoke, but whose gaze always drifted downwards, towards their chests, when he spoke with the young women. At first, these weren’t things I noticed, as I was (especially my freshman year) far too wrapped up in my own issues, but as college wore on, I started to recognize that on top of all the difficulties, struggles and fights for academic and personal growth I had to face as an undergraduate majoring in physics, women majoring in physics had one more thing to deal with, too.

Then there was graduate school. There were many of the same struggles to face: significantly more rigorous academics, more nuanced personal and interpersonal struggles, and again the occasional life crisis. But I was better prepared to deal with it; I was older, I had seen more, traveled more, lived more, and become a stronger person. I had spent a year in the (non-academic) “real world,” and was a more seasoned individual. And I was ready to work harder than I’d ever worked in my life to learn what I was most passionate about.

Professors’ doors were always open, and they were always happy to discuss the areas of their profession (and the courses they were teaching) that they were most excited about. If the conversation ever veered in another direction, it was almost always mutual, and it was never inappropriate or unprofessional, at least to me. But I started noticing things happening around me that I hadn’t noticed before, even as an undergraduate.

The professor who’d talk to a student professionally and politely, then stare at her rear end while she walked away.

The graded assignments that would have flirty little comments and smiley faces, only for the female students.

Gossipy conversations — about other people in the department, obviously — that would mysteriously fall silent whenever certain women walked by (but never the men).

And the way word choice would change ever-so-subtly — like how remarks were “ejaculated” instead of “uttered” — in the presence of certain people.

Now here’s the thing that gets to me: these were only the things I noticed, and I was never the target of these comments, nor did I personally have to deal with any of the ramifications. (And I’m not even a particularly observant person, to be frank.) But something I had wondered about since I first arrived in college at age 18 — why there were so few women professors in the field I had chosen — was no longer a wonder to me. It not only seemed perfectly obvious why there was a gender imbalance at the professorial level in my field; it was a wonder to me that there were as many women as there even were who put up with that level of institutionalized sexism.

Next year will mark a decade since I finished graduate school, and now many of my contemporaries and peers are filling the ranks of the professoriate. I’ve seen lots of young men and women come through a few different departments, each going through their own journey of internal and external discovery. And personally, I find that many of them are attractive, interesting, amazing people. They’re all, universally, deserving of respect.

I want you to think about what you do, professionally — the adults out there — and your path that led you there. That thing you strove for, that journey you took, that support you had (or wish you had) has all gotten you to where you are now, and this is your chance to make it right, once and for all. The institutionalized sexism — or a “socially acceptable” form of sexual harassment — abounds, if only you pay attention and keep your eye out for it. Sometimes, it shows up in places, and at levels, I never would’ve expected to find it.

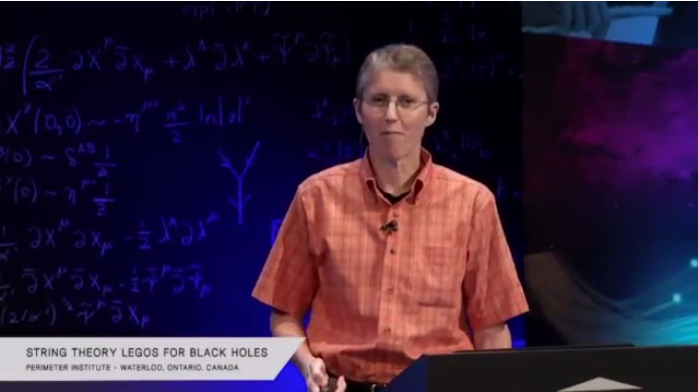

Last week, I live-blogged a talk by theoretical physicist Amanda Peet, and while there were a great amount of comments and discussions focused on her lecture, there was also a great amount focused on… Dr. Peet’s physical appearance. Sure, sometimes I’m judged on my appearance as well — I’m an unusual looking person and I do things to draw attention to myself — but when I talk or write or profess about whatever it is I’m doing professionally, I can always expect to be judged for my merits as a professional. Not for my looks first and then for my scholarship, but for the quality of the work I do. I feel like that’s a privilege, a way I get to play the game of life on “easy mode,” that I wouldn’t get simply if my gender weren’t male. Just as, when I cosplay, I don’t have to worry about my “fan credentials” being questioned, even though I might not be the most hardcore fan out there, I don’t have to be worried that I’ll be judged as “unworthy” of being taken seriously as a scientist or science writer because I don’t (or even do) meet someone’s expectation of what I ought to look like.

Of course, no one wants this to be a problem. No one wants a world where our own backyard — where we work hard to send the message that science, and the wonders and joys of learning about the Universe, is for everyone — isn’t a welcoming, accepting place for everyone who wants that knowledge (and to share it) themselves.

It’s one thing to say don’t do that. Well, duh. That’s not even advice I need to give to most of you; most of us have more sense than that. Most of us are feminists in exactly the way that Rebecca West meant for us to be, subscribing to “the radical notion that women are people.” Most authority figures in my field aren’t sexist, aren’t sexually harassing anybody, and treat everyone based on their own merits as people. But if we want to really change the culture of our field — if anyone in any field wants to change their field’s culture — we have to call people out on their behavior. It might make us uncomfortable to do it, it might alienate people that we actually like and respect, and I might wind up regretting doing it at times, but I do it because it’s the right thing to do. And if we want not only a better world for our mothers, wives, sisters, daughters and granddaughters, but for ourselves as well, no one else is going to do it. It’s up to us.

A couple of years ago, a group of us were filling out forms at work, and one person burst into laughter audible throughout the entire floor. He couldn’t believe, he exclaimed, that there were three options for gender: M, F, and “other.” The idea that there would be an “other” just cracked him up, and he felt like expressing his ridicule was perfectly within his right. I could’ve let it go and not said anything; everyone else seemed perfectly content to do exactly that. But I didn’t. I confronted him, and asked him if he knew about either intersex or trans issues? About people born with gender-ambiguous genitalia or people who felt that who they were on the inside, gender-wise, didn’t match what their body expressed to the world? As he tried to defend his words and actions to me, I realized he very much believed he hadn’t done anything wrong, and didn’t want to have to do anything different in the future. But the truth is, even though he didn’t do anything intentionally wrong, that attitude was a harmful, even a hurtful one, and made the workplace a less inclusive environment for everyone. And that’s the part of it that really needs to change.

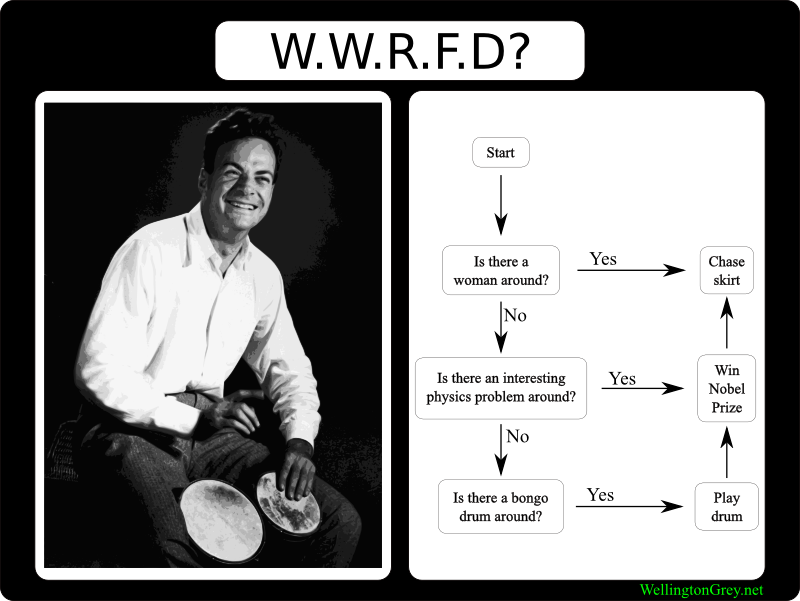

So, talk to me about how awesome a student is at their studies: wonderful! Tell me what you’d like to do to that student, sexually, if you were a little younger? Not okay. Talk to students one-on-one about their work? Perfect. Talk to them one-on-one about their personal lives at their instigation? Believe it or not, that’s fine too. But talk to them about either one of your personal lives at your instigation? Dealing with your issues is not their responsibility. Worship how smart and amazing Feynman was for his contributions to quantum field theory? I’m in awe, too. Trying to be like Feynman in all ways, including the overt misogyny and objectification of women? Not in my house; not in my department.

Look, I’m not perfect, and I’m glad I don’t have to be. I have flaws, we all do, and I’ve never expected anyone else to be perfect, either. I’m not telling you not to forge a connection with your students, peers, professors, or to think whatever you’re going to think about them in the privacy of your own mind. I’m not even saying that no one is ever allowed to find love in weird, taboo places in this world; we’re all entitled to the desires of our own hearts. But I am saying that you have a responsibility to treat every person that comes through — not only your work life but your life in general — with kindness and respect. And not the false kind, not with kindness and respect as they relate to you, but to treat them as people with their own hopes, dreams, fears, demons, abilities and minds. You are to be their resource and their ally. And especially if you’re an authority figure as you relate to them, you are to stand up for them whenever another authority figure steps out of line.

And if every man in science reads this and commits to building this world we want to live in, we can put an end to institutionalized sexism and harassment like this. And men and women both can take their rightful places in this world: alongside one another, as allies, and as people.

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum at Scienceblogs.