Throwback Thursday: Global Warming for Beginners

If you had never heard of global warming before, how would you figure out whether it’s happening?

“There is no question that climate change is happening; the only arguable point is what part humans are playing in it.” –David Attenborough

It’s been a long time since I’ve written anything about global warming, climate change, or most Earth-based environmental topics in general. After all, I’m a physicist — an astrophysicist in particular — and although I’m well-versed in the physics of the Earth and in science in general, it’s not my particular area of expertise.

But with the recent release of the newest IPCC report (on Monday), I’ve had a number of requests to take a look, in-depth, at the issue of global warming, and how one would go about figuring out for themselves whether the Earth was, in fact, warming.

And if it were, how would we figure out whether human activity is playing a significant role in that?

So let’s play pretend for a moment. Let’s pretend the following:

- We’ve never heard of this problem before,

- We’ve never heard anyone else’s opinions — political, scientific or otherwise — on this matter before,

- There are no other concerns such as politics, economics, energy or pollutants, and

- We actually care about the two questions of whether the Earth is getting warmer and, if it is, whether humans are the cause of it.

This is going to be a long post, but sometimes, getting it right takes time. So let’s take that time and get it as right as science knows at present.

Here we go!

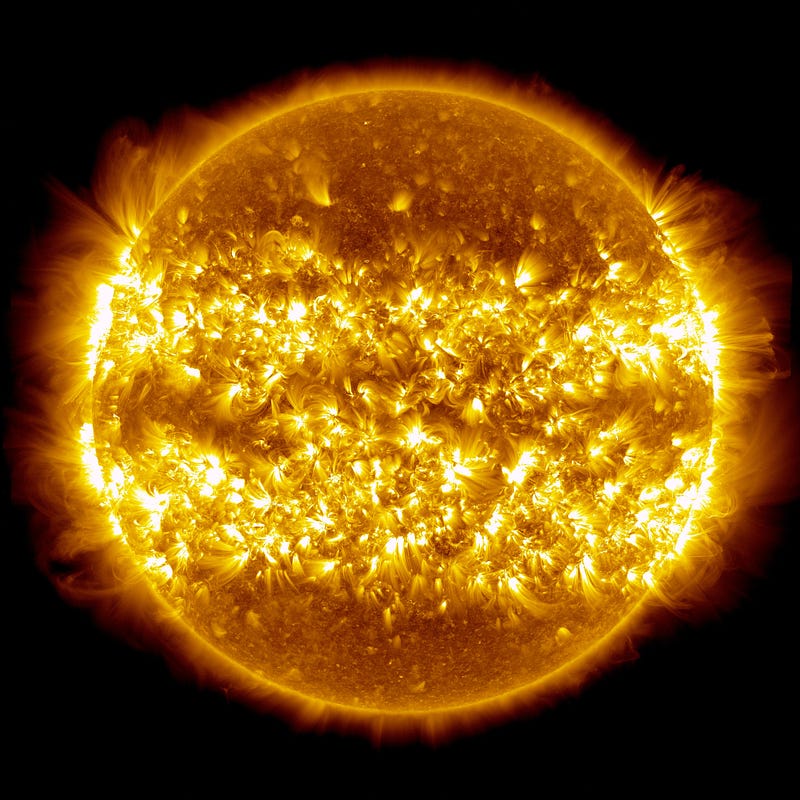

This is the Sun. To an excellent approximation, this is the source of the vast majority of energy that keeps not only Earth, but all the planets at a temperature above just a few Kelvin. (I’m going to speak about temperature in Kelvin, but I’ll put the Celsius and Fahrenheit equivalent in parenthesis from now on; that would be around -270 °C / -455 °F.)

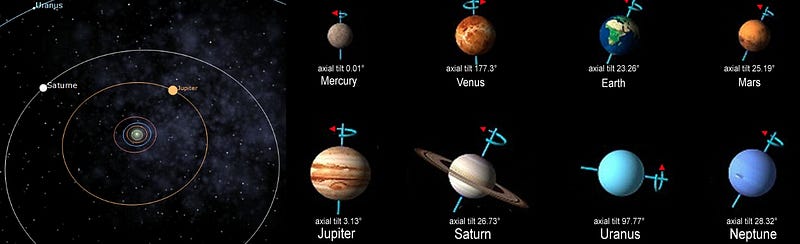

During the day, we absorb energy from the Sun, but during both the day and the night, we radiate energy back into space. This is why temperatures heat up during the day and cool off during the night, something that’s pretty much true for every planet that has both a day side and a night side. We also expect seasons — cool times and warm times — based on both how elliptical a planet’s orbit is and on its axial tilt.

But if these were the only things that determined temperature, then the closest planet to the Sun would be the hottest, and they would all get progressively cooler as we moved farther and farther away. We can check this expectation by starting at the innermost planet and working our way outwards.

Mercury is hot. It’s actually very hot! Being the closest planet to the Sun, and orbiting it in just 88 Earth-days, it achieves a maximum temperature during the day of a whopping 700 Kelvin (427 °C / 800 °F) at its hottest parts. Mercury rotates very slowly, so its night side spends quite a lot of time in the dark, shielded from the Sun; during those times, it gets down to just 100 Kelvin (−173 °C / −280 °F), which is incredibly cold, and far colder than any known naturally occurring temperatures here on Earth. So that’s the story of the closest planet to the Sun, Mercury.

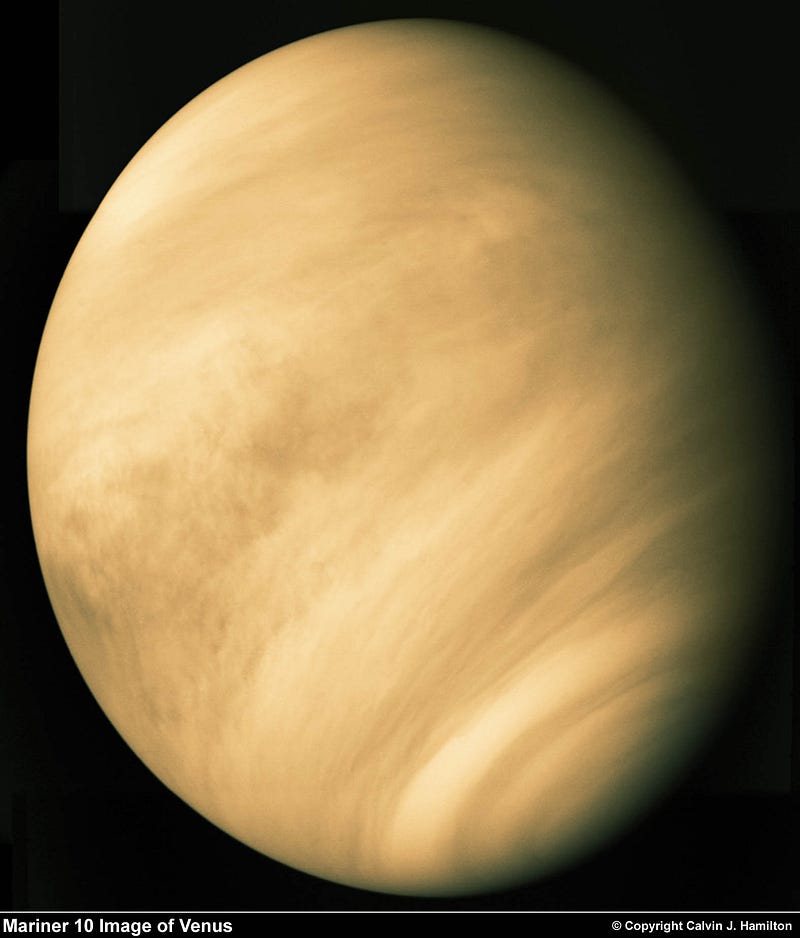

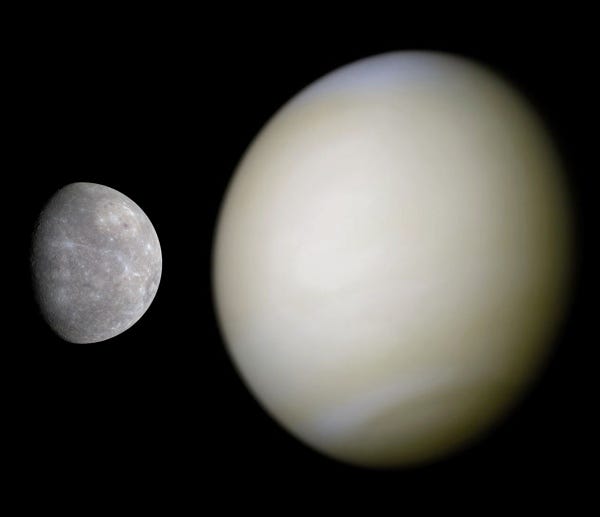

What about the next one out: Venus?

Venus is about twice as far from the Sun, on average, as Mercury is, and it takes about 225 Earth-days to orbit the Sun. It also rotates extremely slowly, spending more than 100 consecutive Earth-days at a time bathed in sunlight and then an equal amount of time in darkness. That’s why it may come as a surprise to learn that Venus is the same temperature at all times, day or night, and that the temperature there averages 735 Kelvin (462 °C / 863 °F), making it even hotter than Mercury!

Okay, so if we want to understand what’s going on with these worlds, we need to ask why?

Comparing these two worlds, there are four very stark differences:

- Mercury is much smaller than Venus,

- Mercury is about twice as close to the Sun as Venus,

- Mercury is much less reflective than Venus, and

- Mercury has no atmosphere, while Venus has a very thick atmosphere.

First off, it turns out that size doesn’t matter very much. If Mercury were twice the size or Venus were half its size, neither one would have its temperature change by any appreciable amount, as the ratio of the sunlight received to the planet’s surface area would be unchanged.

The fact that Mercury is twice as close to the Sun, however, does matter.

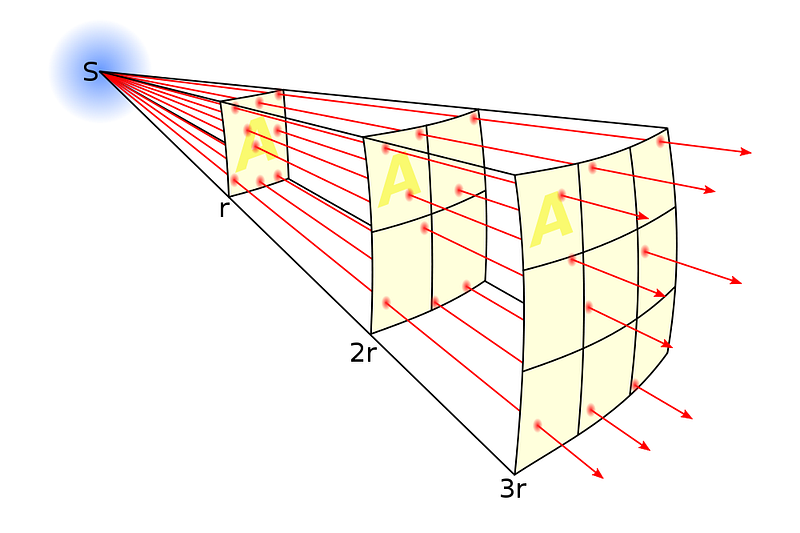

Any object that’s twice as far away from the Sun receives only one fourth the amount of solar energy per-unit-area, which means that Mercury should be receiving about four times as much energy on every part of its surface as Venus receives on its surface.

And yet, Venus is still hotter, which tells us that something important is going on with the other two points.

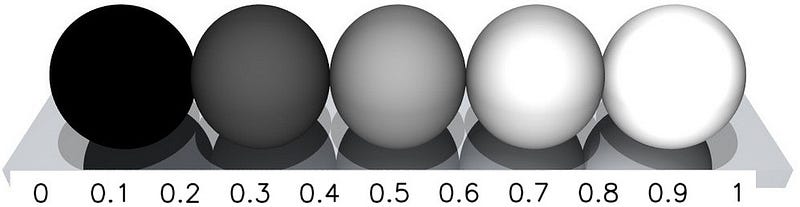

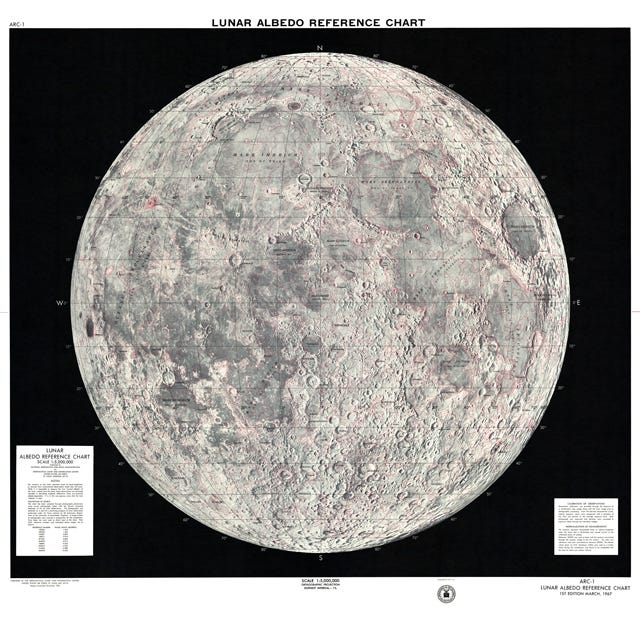

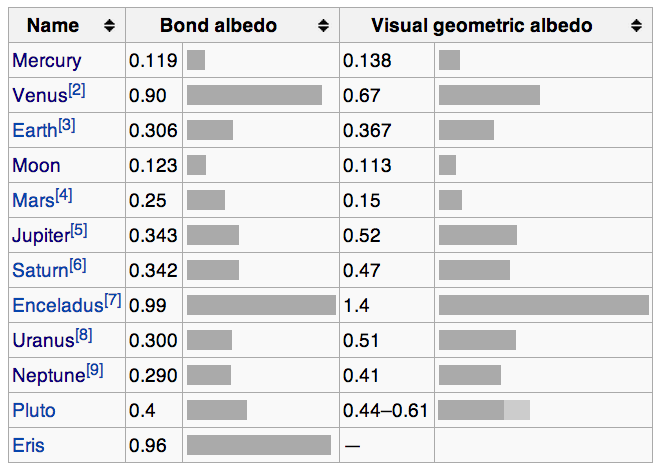

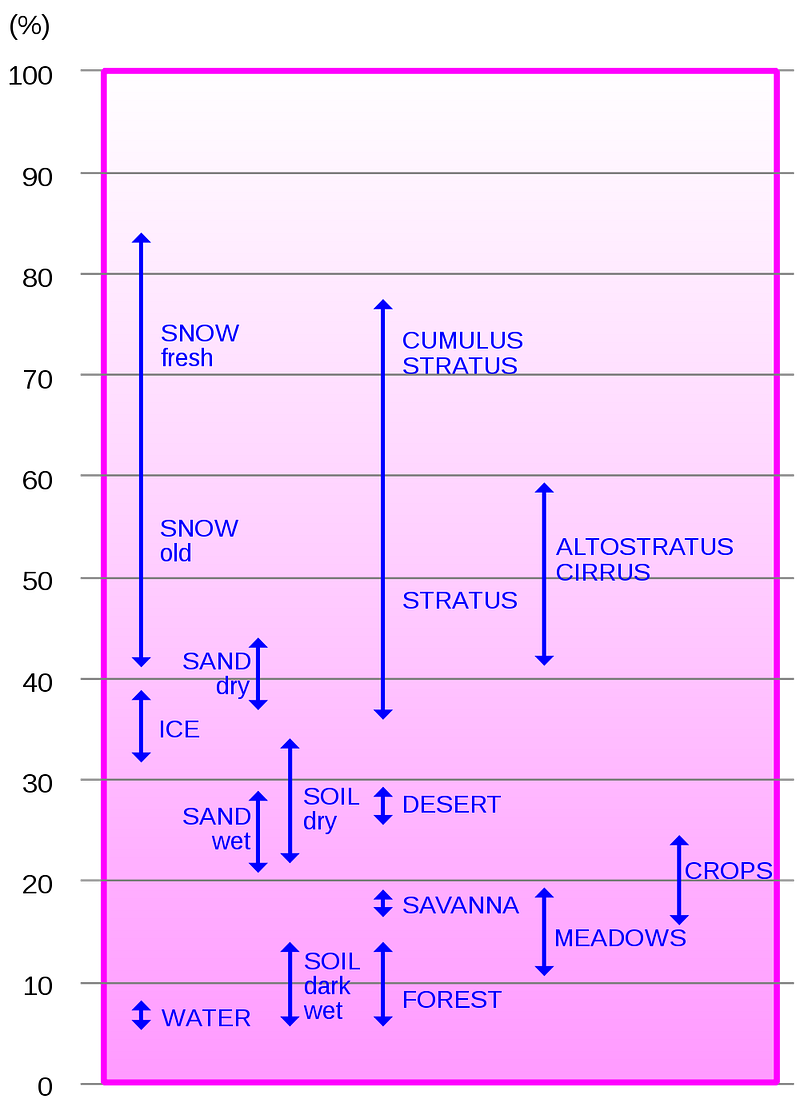

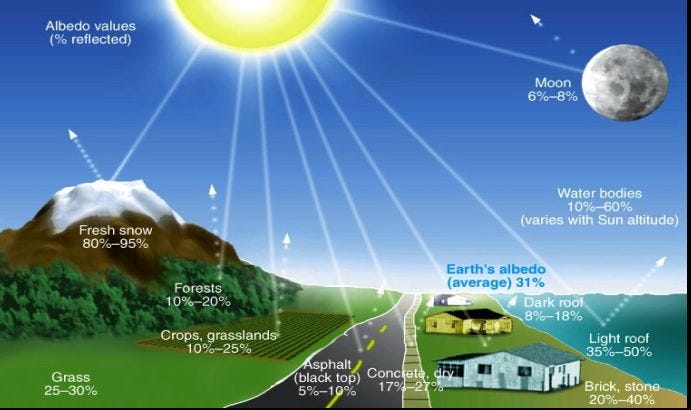

How reflective or absorptive any object happens to be is known as its albedo, which comes from the latin word albus, which means white. An object with an albedo of 0 is a perfect absorber, while an object with an albedo of 1 is a perfect reflector. In reality, all physical objects have an albedo between 0 and 1. You might be familiar with the Moon, which looks like it has a pretty high albedo to our eyes, appearing white in both day and at night.

Don’t be fooled! The Moon’s average albedo is only about 0.12, which means only 12% of the light that hits it get reflected, and the other 88% gets absorbed. The lower an object’s albedo is, the better it is at absorbing light, which means the higher the albedo, the less sunlight actually gets absorbed. (And I’m using Bond Albedo, for those of you who are geoscientists or planetary scientists.)

Mercury turns out to be similar in albedo to the Moon, while Venus’ albedo is by far the highest of all planetary bodies in the Solar System.

So let’s recap so far: even though they’re different in size, that doesn’t matter; Mercury receives about four times as much energy as Venus does per-unit-area; and Mercury absorbs nearly 90% of the sunlight that hits it while Venus absorbs only about 10% of the sunlight that hits it.

And yet, Venus — even during the night — is always hotter than anyplace on Mercury ever is.

What was that fourth point again?

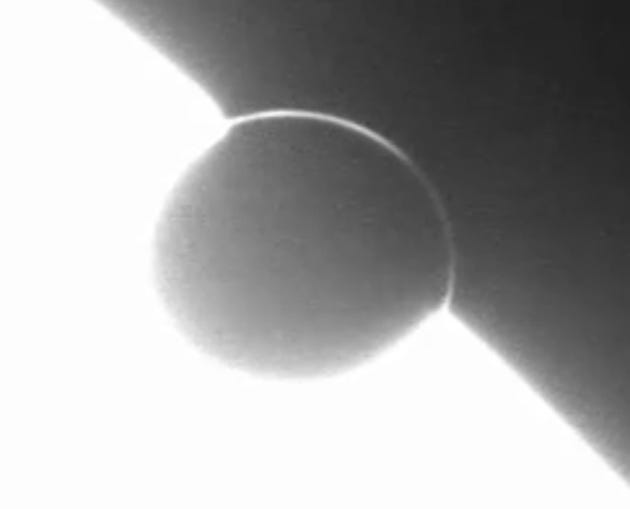

4.) Mercury has no atmosphere, while Venus has a very thick atmosphere. (In fact, those of you who were very astute may have even seen it during 2012’s transit of Venus across the disk of the Sun!)

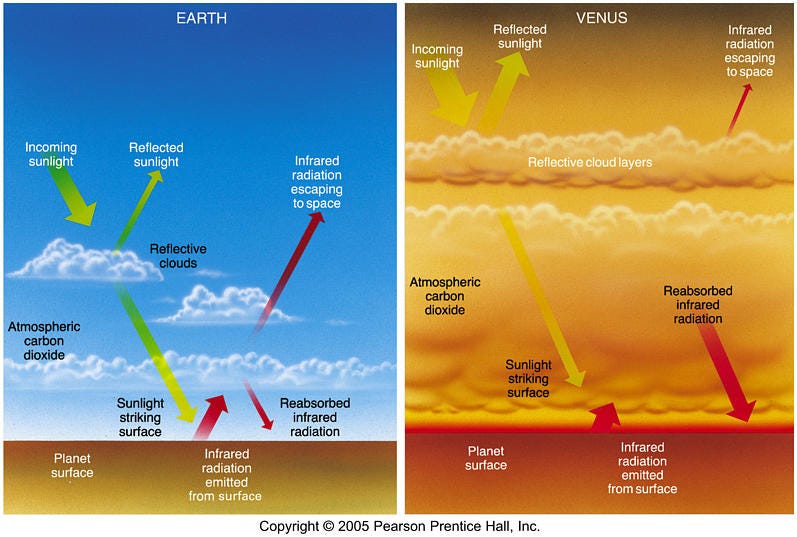

Ah. You see, Mercury and Venus don’t just absorb light from the Sun, the planets then re-radiate that energy as heat back into space. For Mercury, all of that heat goes immediately back into space, but for Venus? It’s got to get through that thick, thick atmosphere, which is difficult.

As it turns out, the atmosphere plays a critical role. The heat that makes it through to Venus stays on Venus for a long time. It stays for long enough that it’s enough to warm the entire night side to the same temperature as the day side (and winds circumnavigating the planet every four days help), and the heat stays for long enough that it allows Venus to consistently be the hottest planet in the Solar System.

What should you take away so far from this? Venus’ thick atmosphere is undoubtedly the reason that Venus is hotter than Mercury. And as far as atmospheres that trap heat the way Venus’ does, the Earth has one, too!

Earth’s is thinner, to be sure, and less effective by far. But even though the magnitude of the effects are vastly different, the principle and the mechanisms are the same. That’s not going to be the whole story, but this is a vitally important part of the story, and something we need to keep in mind as we move forward.

For those of you wondering where Earth fits in on those first three points:

- It’s about the same size as Venus, with a diameter that’s just 5% larger than our nearest planetary neighbor, although that doesn’t matter for temperature.

- It’s about three times as far away from the Sun as Mercury and around 50% farther away than Venus, meaning it receives about one-ninth the amount of radiation per-unit-area as Mercury does, and just less than half the amount Venus does.

- And Earth’s albedo is complicated and inconsistent, due to the fact that we have a variable cloud cover (and clouds are very reflective), seasons (and green continents have a different albedo than brown ones), icecaps and snow cover which change over time, etc. Earth’s albedo is about 0.30 on average, but here’s a chart that illustrates how variable our albedo is as we go from location-to-location and season-to-season.

So even though the Earth’s albedo is complicated, it’s easy to track-and-monitor now that we’ve got satellites in space, and something we can easily account for when we’re trying to model what’s going on with our home world.

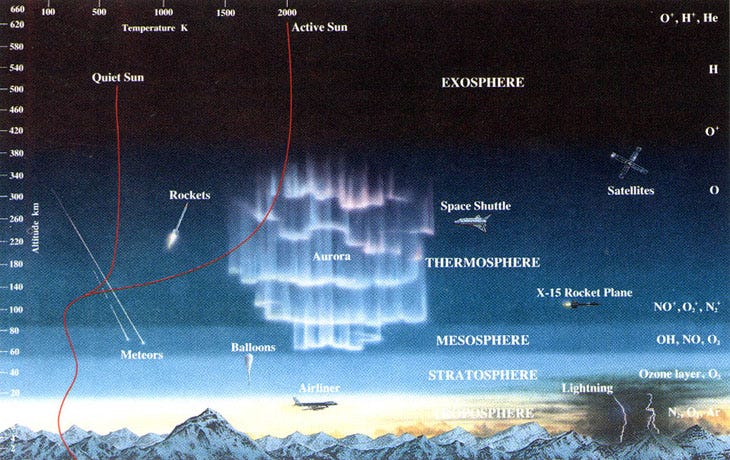

If we want to understand what the temperature of Earth is, why the temperature is what it is, and whether humans have done anything to change it over time, we’ve got to understand the fourth point: Earth’s atmosphere. It’s real, it’s there, and it’s important, but how important?

If we want to understand how this works, we need to start at the source of this energy that planetary atmospheres is so good at trapping: the Sun.

The Sun is, to use a tried-and-true metaphor, hot as hell. At least, that’s true insofar as we can assume hell has a surface temperature of nearly 6,000 Kelvin!

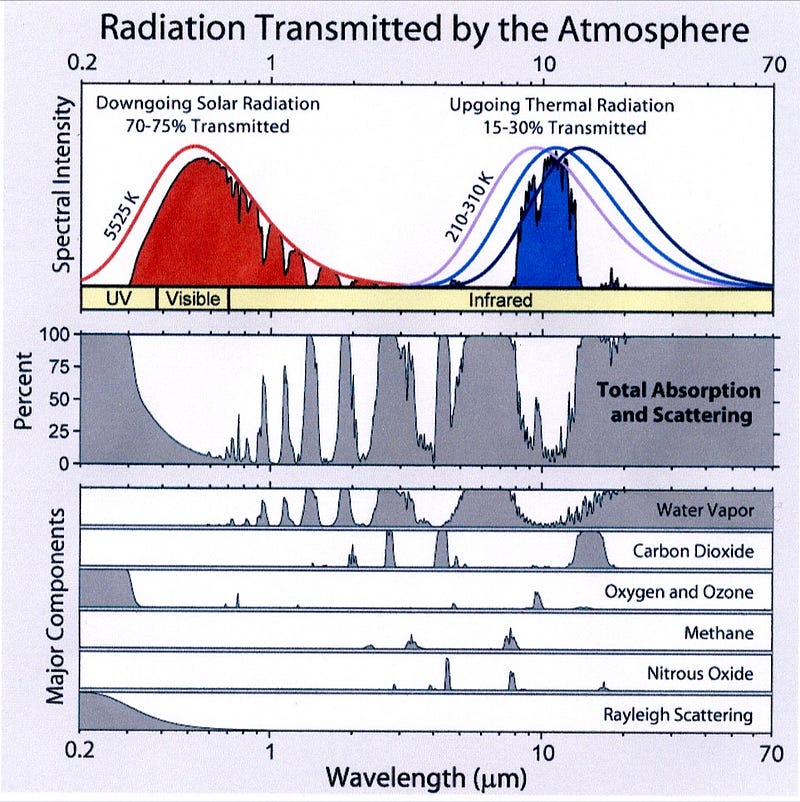

This radiation — like pretty much all radiation — has a very particular energy distribution known as (approximately) a blackbody distribution. (There’s a little extra at very high wavelengths due to the effects of the Sun’s atmosphere.) This ensures that the vast majority of the light that comes from the Sun peaks in the ultraviolet, visible, and infrared parts of the spectrum. That’s what you’d get for pretty much anything you heated up to a temperature of 6,000 Kelvin: an energy spectrum that looks like this.

That’s the energy that the planet’s going to receive. In the case of an airless world like Mercury or the Moon, 100% of that energy reaches the planet’s surface. On a world with clouds like Earth, a substantial fraction might get reflected back into space before ever hitting the surface. But the most exceptional case, once again, is Venus.

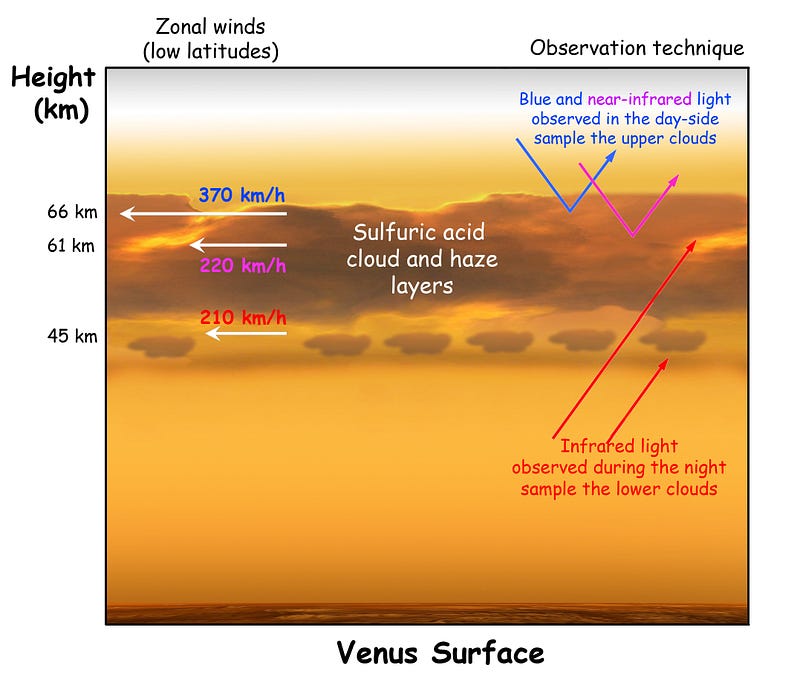

For the sunlight incident on Venus, about 90% of it gets reflected back into space, and only around 10% gets absorbed. Now, here’s the kicker: Venus — like all planets — then proceeds to re-radiate that absorbed energy back into space! If Venus didn’t have an atmosphere, like Mercury or our Moon, 100% of that energy would simply radiate away back into the Universe. Because Venus is at a lower temperature (like any planet), it radiates in the same general fashion that the Sun does: like a blackbody. But the wavelengths that Venus radiates at are shifted to much lower energies, lower frequencies, and longer wavelengths.

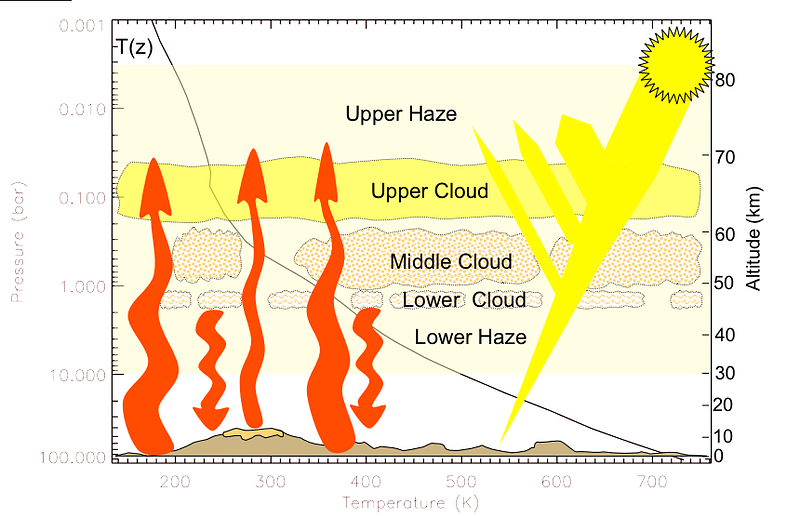

The “problem” is that many of the gases in Venus’ atmosphere — the gases that so easily let the Sun’s light through — are not transparent to the longer-wavelength radiation that Venus gives off! This is compounded not just by absorptive gas, but also by multiple layers of thick, absorptive clouds. So, what happens then, in terms of energy?

The Sun emits energy, Venus absorbs a portion of it, and then when it goes to re-radiate it into outer space, a large percentage of that energy gets absorbed by the atmosphere and re-radiated down to the surface. The surface then re-radiates the energy again, and once again, the atmosphere absorbs most of it, and re-radiates it down to the surface.

And this process continues. The thicker Venus’ atmosphere — and in particular, the thicker the atmospheric components that are opaque to the infrared light that Venus’ surface re-radiates — the longer that energy (in the form of heat) remains on the planet itself.

And that is why Venus is so hot!

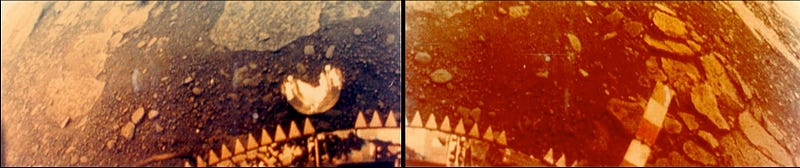

These are the only photos (I know of) ever taken of a lander on the Venusian surface: the Venera 13 lander, which survived a whopping 127 minutes on the scorching 2nd planet from our Sun. (Its sister, Venera 14, survived for a respectable 57 minutes.) That’s not bad, considering that Venus’ surface is hot enough to turn metals like lead to liquid in a matter of seconds!

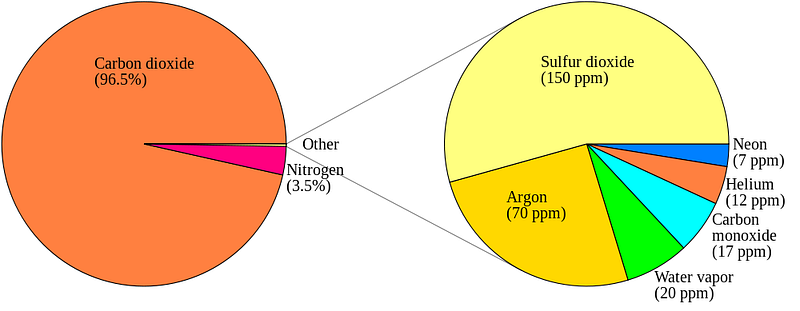

Now, back to Venus’ atmosphere. It is incredibly thick: it contains about 100 times the number of molecules in Earth’s atmosphere, and 96.5% of Venus’ atmosphere is Carbon Dioxide. Most of the rest is Nitrogen, with trace amounts of some other molecules, including a little bit of the familiar Earth-favorite, H2O.

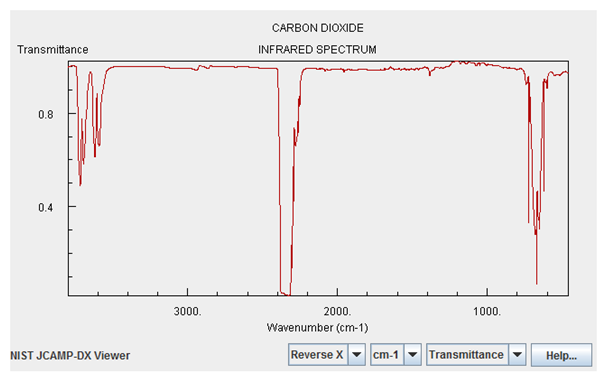

I highlight these two gases above all the others because they have significant absorption features in the infrared. Here’s what the infrared absorption spectrum of Carbon Dioxide looks like:

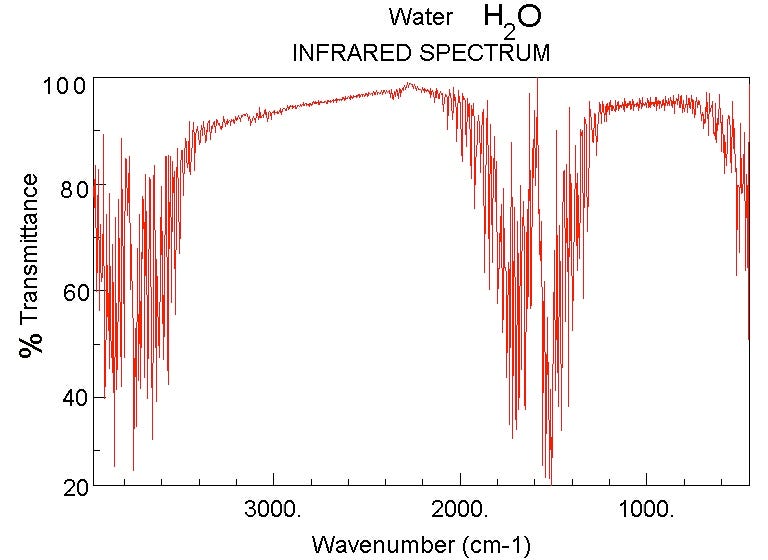

While water vapor has an absorption spectrum that looks like this:

Now, the magnitudes shown here are not tailored for what the concentrations are on Venus. Water vapor is only about a quarter as important on Venus as it is on the graph above, but Carbon Dioxide is — are you ready? — about a quarter of a million (250,000) times stronger than what’s shown.

In other words, the Carbon Dioxide on Venus’ atmosphere is primarily responsible for keeping Venus’ heat from re-radiating back into space, and for trapping it for so long. Here’s a quantitative look at what Venus’ Carbon Dioxide does relative to the heat re-radiated from Venus’ surface.

If Venus had no atmosphere at all — if it were more like Mercury, just a sphere that absorbed most of the sunlight and then radiated it back into space — its temperature would be about 340 Kelvin (67 °C / 153 °F), which is pretty hot, but nothing special.

The effect of Venus’ atmosphere — with all the clouds and gases in there — is to act, metaphorically, like a thick, giant, insulating blanket; it keeps Venus warm via the same mechanism that blankets keep you warm: by absorbing its own heat and re-radiating it back on itself.

A heavier blanket will keep you warmer, and more blankets will increase the effect as well. It’s not hard, with enough blankets, to heat yourself up to well above your normal body temperature; you have to be careful not to overdo it!

The Earth has a much thinner atmosphere than Venus does, but it still manages to act like a blanket.

If it weren’t for the Earth’s atmosphere — if our planet were more like the Moon or Mercury — our planet’s typical temperature would be 255 Kelvin (-18 °C / 0 °F), or well below freezing. We’re not a frozen world, of course: the cloud cover, water vapor, methane and carbon dioxide, among other gases, keep our world about 33 °C (59 °F) warmer than it would be otherwise.

This effect was first discovered nearly two centuries ago by Joseph Fourier and worked out in detail by Svante Arrhenius in 1896. (Remember learning about acids and bases in high school chemistry? Yes, he’s that Svante Arrhenius.)

All of it: water vapor, methane, carbon dioxide, every gas that absorbs infrared light, will act like a blanket. And when we add (or take away) more of those gases from our planet’s atmosphere, it’s like thickening (or thinning) the blanket that the planet wears. This, too, was worked out by Arrhenius over 100 years ago.

So that’s what the Earth’s atmosphere is: it is, depending on how you look at it, either a series of blankets, or a blanket of definitive thickness. You can add-or-remove blankets (or thicken-or-think your blanket) by adding or removing these various infrared-absorbing gases to the atmosphere.

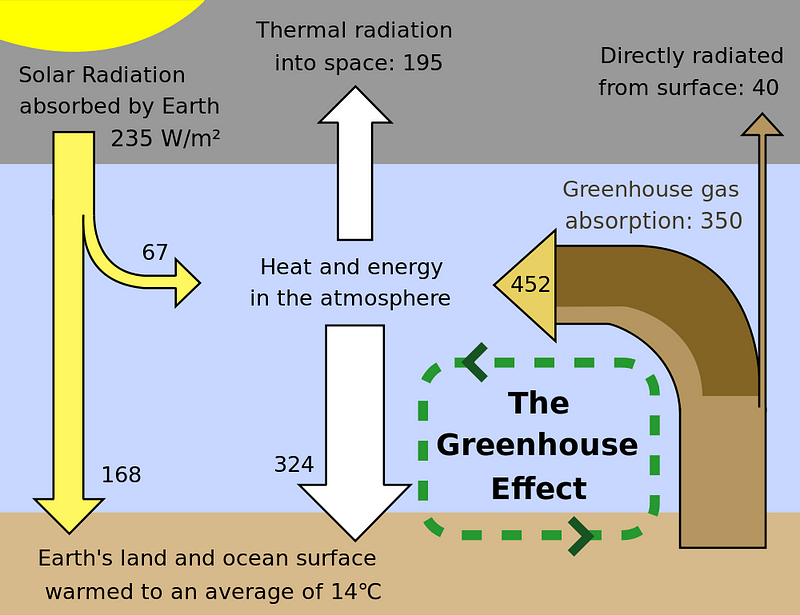

And that’s the idea that powers global warming, the greenhouse effect, and why planets with atmospheres are warmer overall than planets without them. So far, there should be absolutely nothing that anyone could find controversial: planets receive sunlight, reflect part of it and absorb the rest, which they re-radiate, and depending on what’s in their atmosphere, that re-radiated heat can be trapped with widely varying efficiency, warming the planet accordingly.

So what’s Earth’s atmosphere made out of?

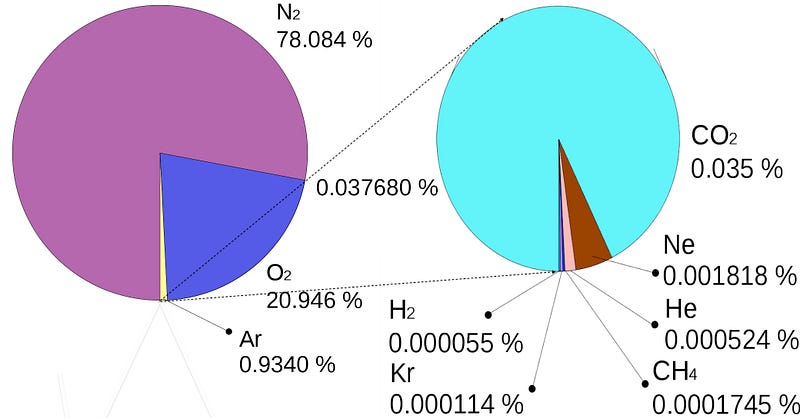

Mostly Nitrogen, which is about 78% of our dry atmosphere, followed by Oxygen, at about 21%. There’s also about 1% argon, an inert gas, followed by small amounts of carbon dioxide, neon (another inert gas), methane, and other trace elements and molecules.

It’s important that I say “dry atmosphere” here, because, well, our atmosphere isn’t ever really dry. We’ve got this pesky little thing on our planet that prevents that from ever really happening.

And by “little”, of course, I mean our oceans, which contain about 300 times the mass of the entire Earth’s atmosphere combined. Because of how chemistry (evaporation, vapor pressure, etc.) works, that adds around an additional 1% to our atmosphere, on average, in the form of water vapor. That number is highly variable, but that’s one component we really have no control over.

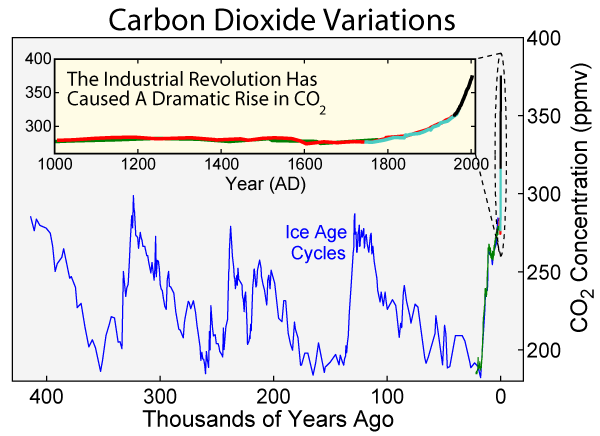

There are others; we don’t control the water vapor, the clouds, the oxygen or the ozone. (At least, not yet.) But the amount of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere has changed substantially over the past few centuries, and that is, without a doubt, due to human activity.

Up until the end of the 18th century, Carbon Dioxide levels were pretty stable at about 270-280 parts-per-million (ppm) in our atmosphere, changing by small amounts due to things like volcanic eruptions, forest fires, and other natural activity. But with the advent of the industrial revolution, all that started to change.

For the first time in natural history, hundreds of millions of years worth of carbon — carbon that had been stored under the surface of the Earth — the remnants of carbon-based organisms that had been buried underground and turned by time into oil, coal, and other resources, was being burned and returned to the atmosphere, all at once.

You can do the math for yourself, and you’ll find that since the dawn of the industrial revolution, we have burned-and-added about 1.5 trillion metric tonnes of Carbon Dioxide to the atmosphere.

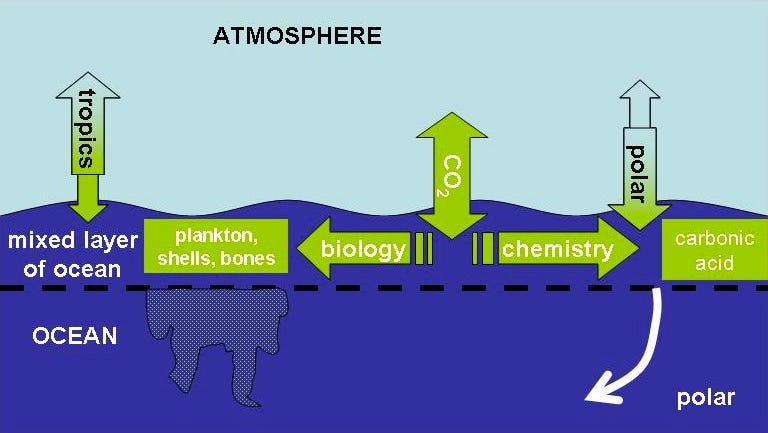

This should be a little surprising, because if you do the math about how much Carbon Dioxide is in our atmosphere right now, it’s “only” about 2.1 trillion metric tonnes (or about 400 ppm), which is an increase of only around 0.7 trillion tonnes from pre-industrial revolution levels (270 ppm). So where did the other 0.8 trillion tonnes go?

Into the ocean. Any idea what you get when you mix carbon dioxide (CO2) with water (H2O)? You get H2CO3, also known as carbonic acid. (And yes, it was our old buddy Arrhenius who figured that out, too.) If you’ve ever heard of ocean acidification, this is where it comes from, and this is undoubtedly what’s causing it.

But that’s not what all this is about; the issue at hand is global warming. Based on what we just went over, we know that planets absorb light in mostly the ultraviolet, visible, and near infrared, and then radiate that energy back into space in the mid-and-far infrared. At least, they try to, unless something in the atmosphere absorbs some of that infrared energy, and re-radiate it back to the planet’s surface. How good are Earth’s gases at doing that?

They’re only okay at it, important enough to have warmed the planet by (if you remember) 33 °C (59 °F) over what it would be without an atmosphere at all. In fact, of that amount, atmospheric science has been able to quantify how much is due to the different components:

50% of the 33 K greenhouse effect is due to water vapor, about 25% to clouds, 20% to CO2, and the remaining 5% to the other non-condensable greenhouse gases such as ozone, methane, nitrous oxide, and so forth.

In fact, if we filter the effects of water vapor out, this is what the re-radiation of different gases contributes to our planet’s heat content.

So if 20% of our planet’s greenhouse effect is due to Carbon Dioxide, and we’ve increased the Carbon Dioxide level by 50%, does that mean we’re in for another 3.3 °C (5.9 °F) of warming?

Maybe, but not necessarily. There are other factors that come into play, and when you do something to heat the Earth up, it has many natural mechanisms to attempt to regulate itself.

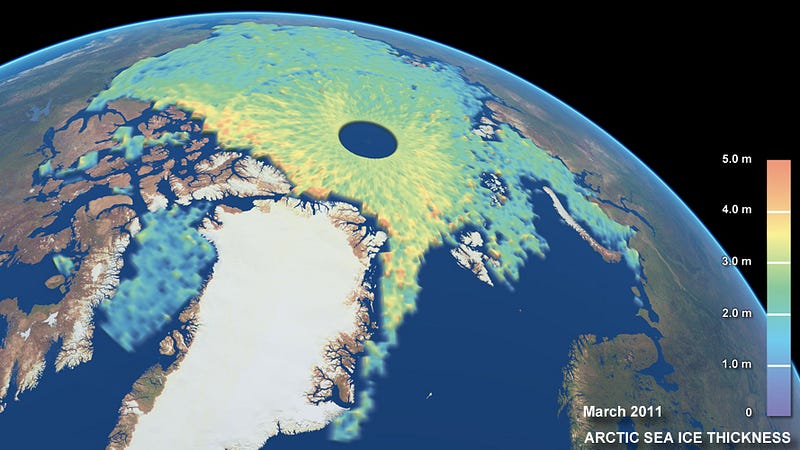

There’s latent heat stored in glaciers and icecaps, and if you start to melt them, that releases cooler water into the oceans, lakes and rivers. For small increases in Carbon Dioxide, plant activity will increase, removing some of that greenhouse gas from the atmosphere.

The danger is in what happens if we add too much Carbon Dioxide to the atmosphere too quickly, which could mean the Earth’s temperature would start to rise in response to an increased greenhouse effect.

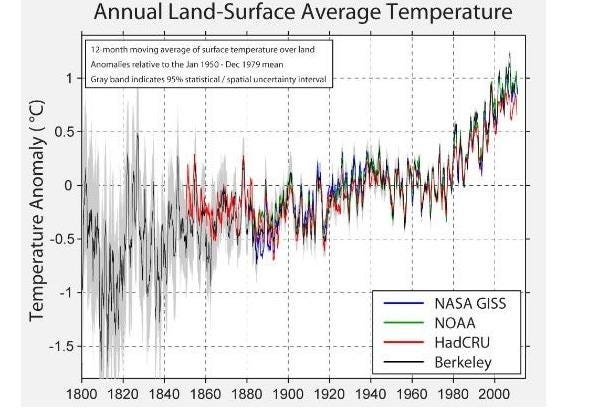

And that’s exactly what we’ve seen happen. We had what appeared to be normal temperature fluctuations — consistent with what was historically observed — up until the late 1970s. But after that, coincident with an exponentially rising increase in Carbon Dioxide concentrations, the average temperature of the Earth began rising, too, and quickly.

This rise has continued, uninterrupted (despite some fraudulent claims to the contrary), to the present day. Some people do error-riddled cherry-picking of the data to claim that the temperature has stopped rising, which statistically robust methods show is simply untrue.

Other methods of showing global average temperature vs. time — such as taking the average global temperature over each decade — show the same, steady increase over time since the end of the 1970s.

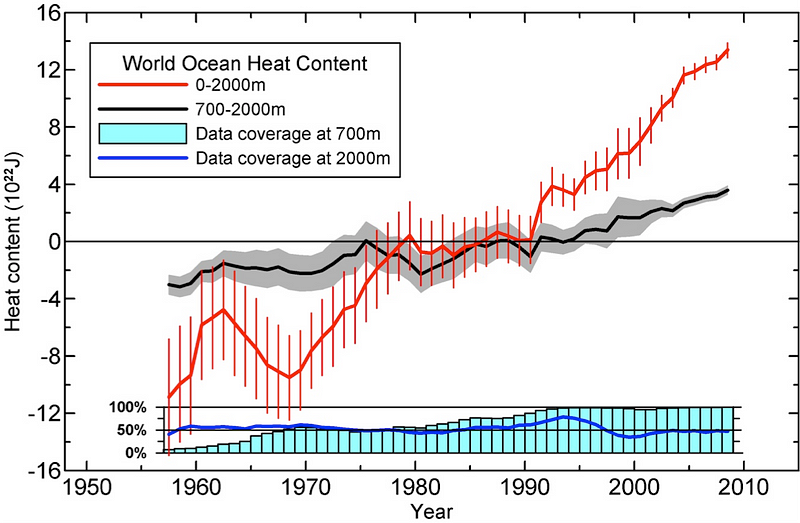

The vast majority of the heat, by the way, isn’t going into the Earth’s surface or the Earth’s atmosphere; that’s just the places where it’s easiest for humans to measure the temperature on Earth.

As you’d expect, given that the Earth’s oceans have a low albedo, cover the majority of the surface, convect easily, and run around 2-3 miles deep on average, the vast majority of the heat increase has wound up in the oceans.

So, undoubtedly, the Earth has warmed, and — to the best of our measurements — it appears to be warming still.

There could have been other, natural explanations for this warming, such as increased solar output, which has been correlated with temperature increases in the past. But, in fact, the opposite has been happening, and the current solar cycle is showing substantially decreased solar activity, which should’ve resulted in a cooling effect, had all other things been equal.

It cannot be proven that human activity is the cause of global warming, but based on what we know about planetary science, Earth’s atmosphere, human activity and the warming we’re observing, it seems very, very unlikely that anything else could be the cause. Not the Sun, not volcanoes, not any natural phenomenon that we know of.

Earlier this week, a broad scientific report (the IPCC’s AR5) came out, and they’ve take a full, in-depth look at this and other global warming issues. You can get the full report here, but because this is already so long, here’s the summary:

Now that you know that global warming is real, and now that you understand why it’s really likely that it’s caused by human activity, I hope you’ll start asking what the right way is to start addressing this problem. I’d like for humans to live happily and successfully on this world for thousands of generations to come, and that starts with taking care of this world today.

This is the best information we have and the most complete picture we’ve been able to build for ourselves. Let’s listen to it, and let’s take care of our world, for our own sakes, and for the sakes of all the humans and living creatures who’ll come after us on this world.

This article originally appeared as a three-part series on Scienceblogs, and has been updated in light of recent findings. If you’d like to weigh in and leave a comment, head to the Starts With A Bang forum over on Scienceblogs today.