This Is Why Space Needs To Be Continuous, Not Discrete

We might live in a quantum Universe, but we’ll violate the principle of relativity if space is discrete.

If you try and divide matter into smaller and smaller chunks, you’ll eventually arrive at the particles we know of as fundamental: the ones that cannot be decomposed any further. The particles of the Standard Model — quarks, charged leptons, neutrinos, bosons, and their antiparticle counterparts — are the indivisible entities that account for every directly measured particle in our Universe. They are not only fundamentally quantum, but discrete.

If you take any system made up of matter, you could literally count the number of quantum particles in your system and always wind up with the same answer. But that’s not true, as far as we can tell, of the space that those particles occupy. Observationally and experimentally, there’s no evidence for a “smallest” length scale in the Universe, but there’s an even bigger theoretical objection. If space is discrete, then the principle of relativity is wrong. Here’s why.

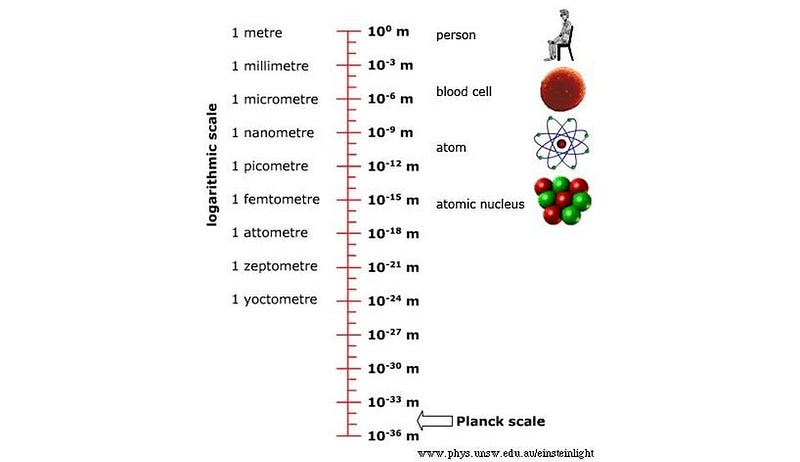

Just as you can learn what matter is made of by dividing it up into smaller chunks until you get something indivisible, you might intuit that you could do the same thing to space. Perhaps there’s some smallest scale you could eventually reach where you could divide it no further: some smallest unit of space on the smallest scales.

If this were the case, our notions of a continuous Universe would only be an illusion. Particles instead would jump from one discrete location to the next, perhaps in discrete chunks of time as well. The speed of light would be the cosmic speed limit at which those jumps occur: you can move no faster than one unit of space in a given period of time. Instead of motion through space and time flowing freely from one location and moment to the next, they’d only appear to do so on the large, many-jump scales we’re capable of perceiving.

Today, we have two separate theories that govern how the Universe works: quantum physics, which governs the electromagnetic and nuclear forces, and General Relativity, which governs the gravitational force. Although we fully expect that there ought to be a quantum theory of gravity — there must be if we ever hope to answer questions like “what happens to the gravitational field of an electron as it goes through a double slit?” — we don’t know what it looks like.

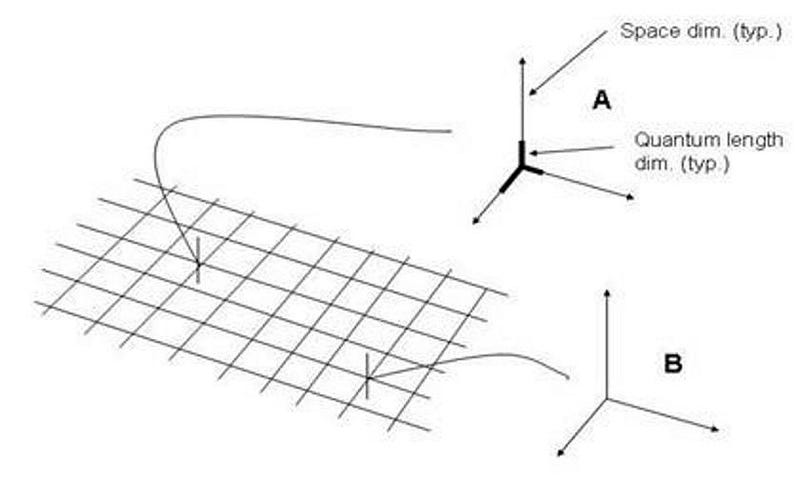

But one possibility that’s often floated is that a quantum theory of gravity could lead to a discrete structure for space and time, which approaches like Loop Quantum Gravity require. But the notion of space and/or time being broken up into finite, indivisible chunks didn’t start there. It’s an idea that first arose nearly a century ago, with Heisenberg finding its origins in the idea of the quantum Universe itself.

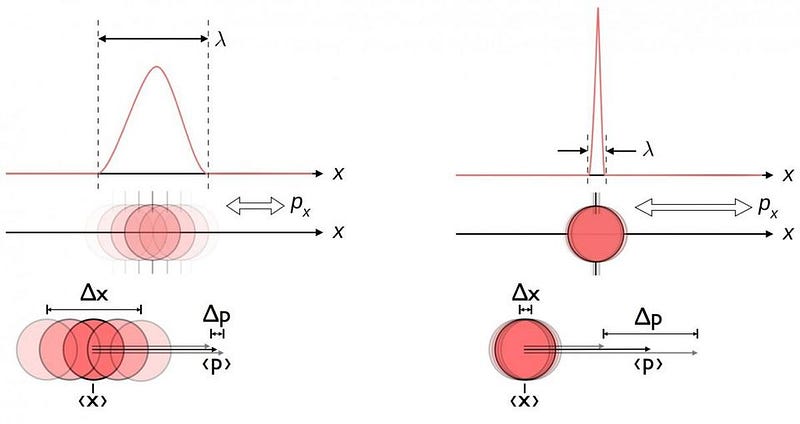

Heisenberg is most famous for the uncertainty principle, which is a fundamental limitation on how precisely you can measure-and-know two different properties of a system simultaneously. For example, these fundamental limits apply to:

- position and momentum,

- energy and time,

- and angular momentum in two perpendicular directions.

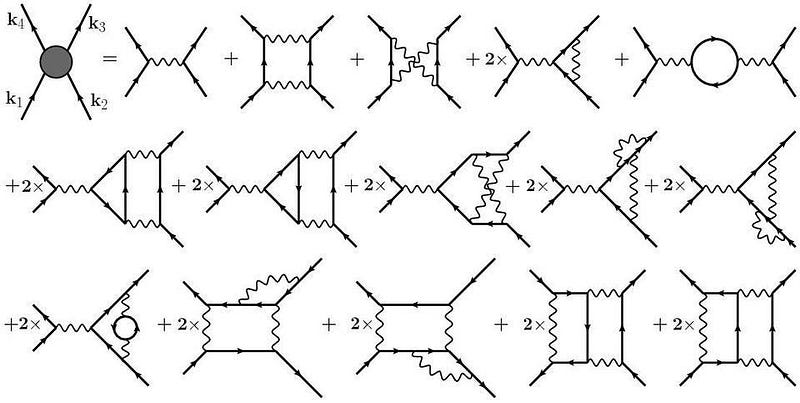

But Heisenberg also demonstrated that when we tried to promote our quantum theories of individual particles to fully quantum field theories, some of the probability calculations we’d perform would give nonsense answers, like “infinite” or “negative” probabilities for certain outcomes. (Remember, all probabilities must always be between 0 and 1.)

It was here that his brilliant stroke came in: if you postulated that space wasn’t continuous, but instead had some minimum distance scale inherent to it, those infinities disappeared.

This is the difference between what physicists call “renormalizable,” where you can make the probability of all possible outcomes sum up to 1 without any single outcome having a probability outside of the 0-to-1 range, and “non-renormalizable,” which gives you the forbidden nonsense answers. With a renormalizable theory, we can calculate things sensibly, and get physically meaningful answers.

But now we run into a problem: the principle of relativity. Put simply, it says that the rules that the Universe obeys should be the same for everyone, regardless of where (in space) they are, when (in time) they are, or how quickly they’re moving with respect to anything else. There’s no issue for the where and when parts of this statement, but the “how quickly you’re moving” part is where things start to break down.

In Einstein’s relativity, an observer who’s moving with respect to another observer will appear to have their lengths compressed and will appear to have their clocks run slow. These phenomena, known as length contraction and time dilation, were known even before Einstein, and have been experimentally verified under a wide variety of conditions to enormous precision. All observers agree: the laws of physics are the same for everyone, regardless of your position, velocity, or when in the Universe’s history you make your measurements.

But if there’s a minimum length scale to the Universe, that principle goes out the window, and leads to a paradox of two things that each must be true, but cannot be true together.

Imagine there’s a minimum length scale for someone at rest. Now, someone else comes along and starts moving close to the speed of light. According to relativity, that length that they’re looking at has to contract: it must be a smaller length than it is for someone at rest.

But if there’s a fundamental, minimum length scale, every observer should see that same minimum length. The laws of physics need to be the same for all observers, and that means everyone, regardless of how fast they’re moving.

That’s an enormous problem, because if there truly is a fundamental length scale, then different observers who move at different speeds relative to one another will observe that length scale to be different from one another. And if the fundamental length governing the Universe isn’t the same for everyone, than neither are the laws of physics.

That’s a challenge for both theory and for experiment. Theoretically, if the laws of physics aren’t the same for everyone, then the principle of relativity is no longer valid. The CPT theorem, which states that every system in our Universe evolves identically to the same system where we’ve

- replaced all the particles with antiparticles (flipped the C-symmetry),

- reflected every particle through a point (flipped the P-symmetry),

- and reversed the momentum of every particle (flipped the T-symmetry),

is now invalid. And the concept of Lorentz invariance, where all observers see the same laws of physics, has to go out the window as well. In General Relativity and the Standard Model, these symmetries are all perfect. If there’s a fundamental length scale to the Universe, one or both of them are, in some way, wrong.

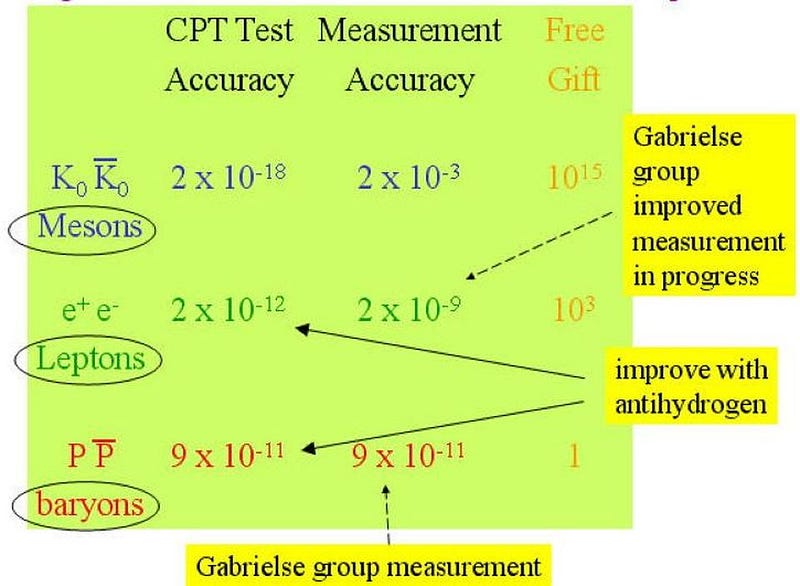

Experimentally, there are enormously tight constraints on violations of all of these. Particle physicists have probed the properties of matter and their antimatter counterparts under a huge range of experimental conditions, for stable, long-lived and short-lived particles. CPT has proven to be a good symmetry to better than 1 part in 10 billion for protons and antiprotons, better than 1 part in 500 billion for electrons and positrons, and better than 1 part in 500 quadrillion for kaons and anti-kaons.

Meanwhile, Lorentz invariance is observed to be a good symmetry from astrophysical constraints up to energies in excess of 100 billion GeV, or some 10 million times the energies reached at the Large Hadron Collider. A controversial but fascinating paper out just last month constrains Lorentz invariance violation to energies even beyond the Planck scale. If these symmetries are broken, the evidence has yet to show even a hint of appearing.

In General Relativity, matter and energy determine the curvature of space and time, while spacetime curvature determines how matter and energy move through it. In both General Relativity and Quantum Field Theory, the laws of physics are the same everywhere and for everyone, regardless of their motion through the Universe. But if space has a fundamentally minimum length scale, then there is such a thing as a preferred frame of reference, and observers in motion relative to that frame of reference will obey different laws of physics from the preferred reference frame.

This doesn’t mean that gravity isn’t inherently quantum; space and time can be either continuous or discrete in a quantum Universe. But it means that if the Universe does have a fundamental length scale, that the CPT theorem, Lorentz invariance, and the principle of relativity must all be wrong. It could be so, but without the evidence to back it up, the idea of a fundamental length scale will remain speculative at best.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.