This Is Why Betelgeuse (Probably) Isn’t About To Explode

Despite its changing shape and its unprecedented dimming, a supernova this year, decade, or even century is highly unlikely.

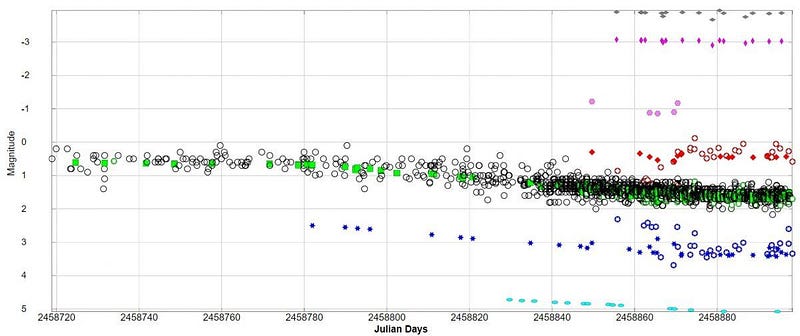

For months, skywatchers have enjoyed a view of the night sky that’s wholly unfamiliar to anyone alive today: a sky where Betelgeuse, one of the 10 brightest stars in the sky, has dimmed to around #25, about the same as the stars in Orion’s belt. The dimming appears to have stabilized for now; Betelgeuse has remained constant since late January. This is the faintest Betelgeuse, one of the closest red supergiants to Earth, has ever appeared in our lifetimes.

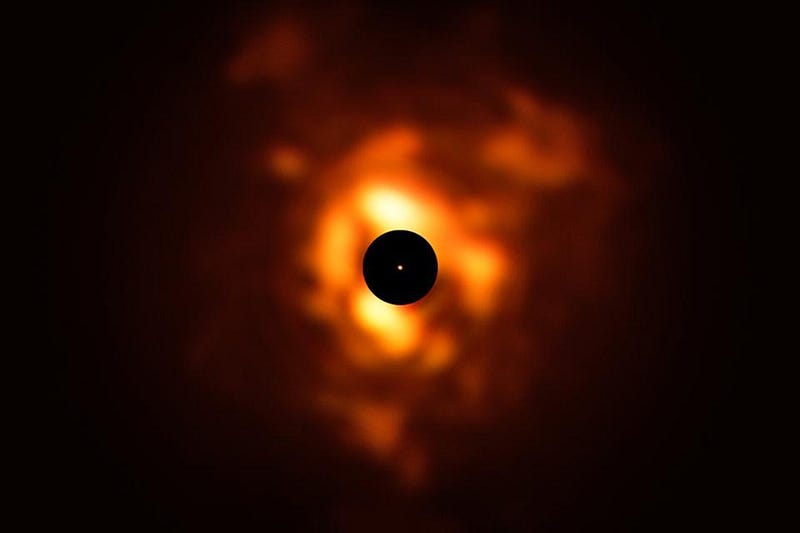

Just a few days ago, the first image of the star’s shape since the dimming began was released, showing significant changes since it was last observed in shape, brightness, and its luminous extent. Speculation about Betelgeuse’s near-term fate, which is expected to eventually end in a supernova, are running rampant, with everyone wanting to know if and when it will explode. But the answer is probably “not anytime soon,” and astronomers know this to be the case. Here’s the reason why.

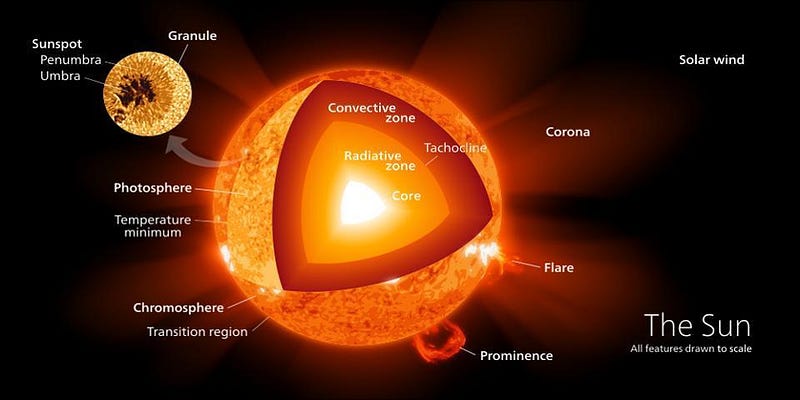

Despite being a red supergiant star, Betelgeuse has a lot in common with our own Sun. They both possess a core region where nuclear fusion occurs. They both have large radiative zones, where the light and energy generated from the core’s fusion reactions propagate outward, taking a “random walk” path to get there. And they both have diffuse photospheres, where the light, having propagated to the star’s outermost layers, finally gets released into the Universe.

Like all stars, the Sun and Betelgeuse both transport energy in a complex fashion, driven by large-scale electric currents, magnetic fields, moving particles, and thermally driven convection. The science of magnetohydrodynamics dictates how this all plays out in detail, with processes that occur in the core eventually propagating to the photosphere and influencing what we wind up observing.

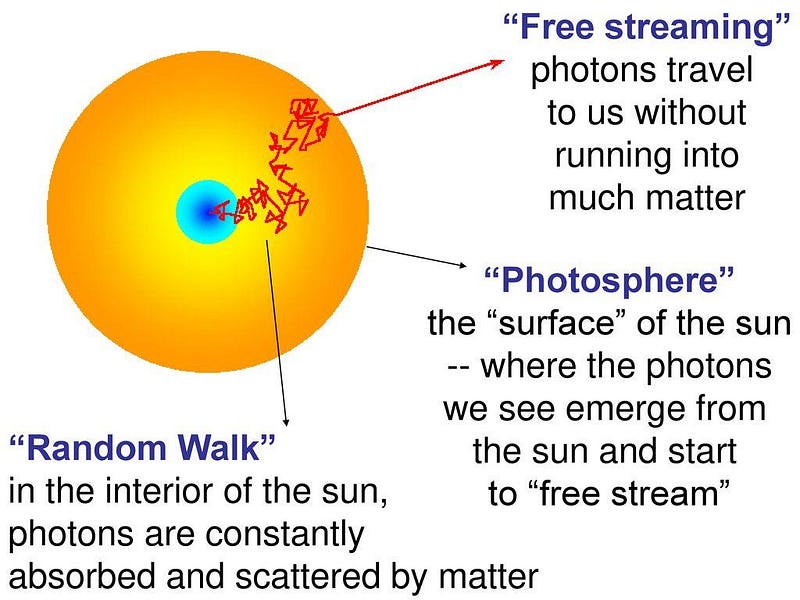

However, what happens in the core takes a very long time to make its way to the photosphere. When light elements fuse into heavy ones in a star’s core, energy is produced. Those energetic quanta collide with other particles in the star’s interior, exchanging energy and causing any photons to bounce around in random directions. Given the sheer number of particles inside a star and a star’s typical size, it takes an enormous length of time for any change in a star’s core to propagate to what we loosely think of as the star’s surface.

In our own Sun, that timescale is between 100,000 and 200,000 years: the typical amount of time it takes the energy produced in a fusion reaction to reach the photosphere. The light that we see from our own Sun might take a little more than 8 minutes to reach our eyes from the moment it leaves the photosphere, but it takes over 100,000 years for the light produced in the core to even reach the photosphere in the first place.

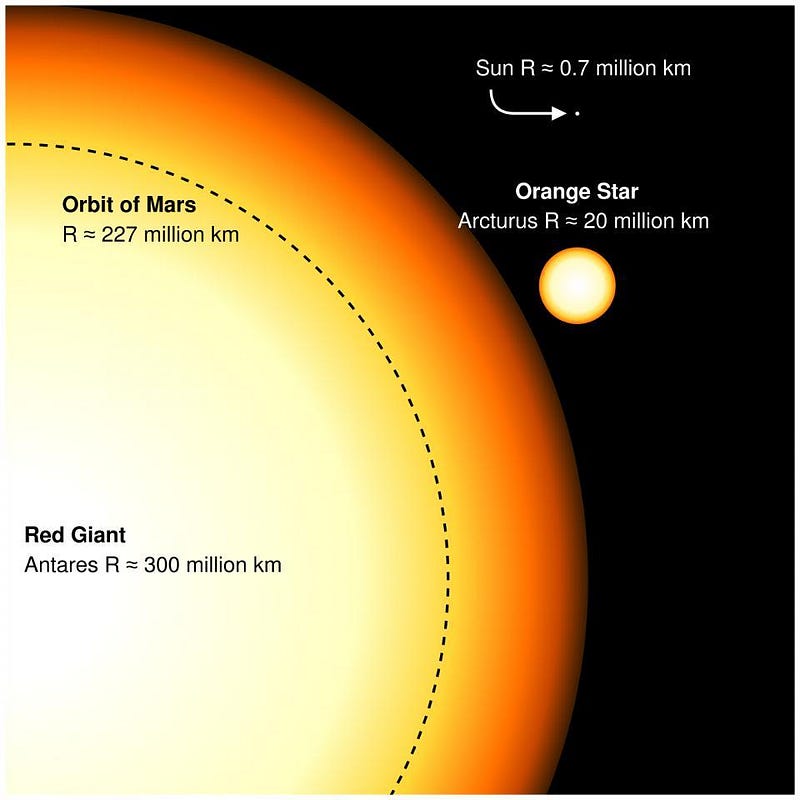

With a star like Betelgeuse, which is significantly more massive (about 20 times our Sun’s mass) but also much larger (about the size of Jupiter’s orbit), this is still a major problem. It’s absolutely true that the outer layers of red supergiant stars do vary, consisting of a number of large convective cells that go down a significant depth into the star’s interior. Inside a star like this, energy is exchanged and transported between the various layers in a complex and intricate manner, with energy from the core still taking a very long time to propagate to the star’s outer layers.

It’s not as bad for a star like Betelgeuse as ~100,000 years, which is much lower in density (and hence has a lower rate of particle interactions) than our Sun, but it still takes somewhere on the order of millennia for changes occurring in its core to propagate to its photosphere.

That said, we absolutely do see that Betelgeuse, like all red supergiants that we’ve either observed or simulated, is extremely variable in shape, size, brightness, and brightness distribution. The changes that occur in its outermost layers occur on timescales of a few months, rather than thousands of years. Even violent events, such as the ejection of matter (which is what’s likely substantially dimming the star), are unrelated to what’s occurring in the core.

Which is a bit unfortunate, because all we can observe is what’s happening at that outermost layer of Betelgeuse: the photosphere. We can make observations of what happens outside of that photosphere as well, where we use multiwavelength observations to find and map out an enormous amount of extended matter that was doubtlessly ejected over centuries and millennia past.

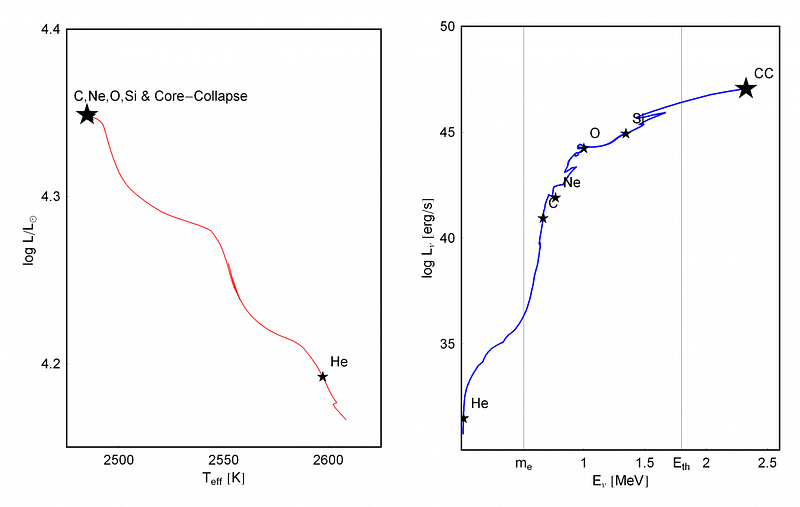

But none of that gives any indication of what’s actually occurring in the core, which is the information we actually need to determine when or whether Betelgeuse is most likely to go supernova. Inside a red supergiant like this, we fully expect that the star has moved on to the stage where it’s fusing carbon in its core. In order to go supernova, however, it needs to proceed from:

- fusing carbon in its inner core,

- to fusing neon in its inner core,

- to fusing oxygen in its inner core,

- to fusing silicon in its inner core.

Only when the silicon in the core has been exhausted, leaving an “ash” remnant of iron, nickel and cobalt (which will not fuse and release energy under these conditions), will the supernova actually occur.

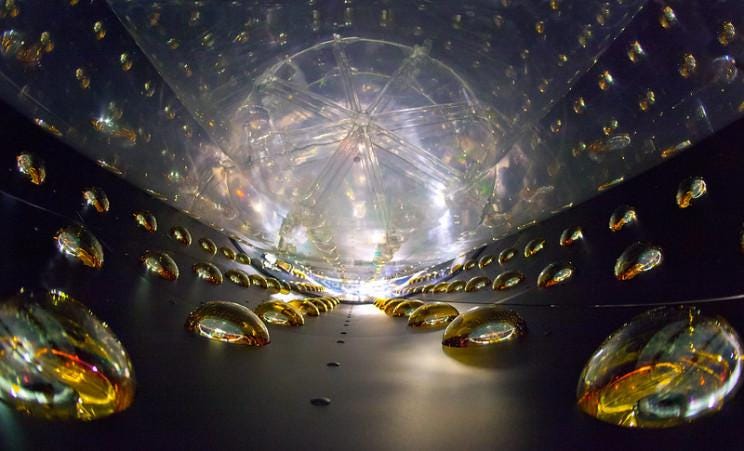

Unfortunately, our understanding of stars is good enough that we are absolutely certain that none of the surface changes we’ll see are any indication of what’s occurring in the star’s core. The only observable signal we’ll have isn’t visual at all, but rather comes in the form of neutrinos. While transitioning between carbon, neon, oxygen and silicon-burning offer no change in the luminosity or temperature of the star, the neutrino spectrum does change in both energy-per-neutrino and the total flux of neutrinos.

Even from Earth, some 640 light-years away from Betelgeuse, the final stages of this transition will be noticeable. During silicon-burning, there will come a stage where the energy that each (anti-)neutrino is produced with is sufficient that it will trigger an inverse beta decay reaction in our terrestrial detectors, producing scores of these interactions during the final few hours of the star’s life.

The neutrino signal that we’ll receive from Betelgeuse just before it goes supernova is, as far as we can tell, the only early-warning system we have with any sort of physical merit. What we’ve been seeing with our own eyes and telescopes is fascinating, but merely evidence of variability in supergiant stars, something that’s been known and studied very well for hundreds of years. What’s occurring with Betelgeuse isn’t even that unusual; it’s only remarkable because Betelgeuse is so close and so familiar.

Of all the stars we’ve ever observed where a supernova did eventually occur, we have never yet uncovered a correlation between a dimming event such as this and a supernova. As much as we might hope for such a spectacular, rare, and nearby event like a supernova to occur in our lifetime, the recent faintness of Betelgeuse doesn’t point in that direction at all.

What we’re seeing today, based on the changing brightness of Betelgeuse, is consistent with something much more mundane than, “it’s about to go supernova.” Instead, what appears to be going on is simply a large ejection event, where matter from Betelgeuse’s outer layers — originating perhaps a billion kilometers from the core — is spit out from the star’s interior.

Once this material makes in beyond the photosphere, it expands and cools, where it begins absorbing and obscuring portions of the starlight. The fact that one portion of Betelgeuse appears fainter than the remainder is suggestive of where this ejection event has occurred. If this is what’s truly going on, we can fully expect that, over the coming months, the brightness will remain stable, followed by a gradual re-brightening to its original status. By 2022 or 2023 at the latest, Betelgeuse should be back in the top 10 for brightest stars in the sky.

Even though it’s unlikely that Betelgeuse is about to explode, we must keep in mind that this is both a possibility and an inevitability. When that finally does occur, it will become the most widely-viewed astronomical event in human history, visible to everyone on Earth over the course of a year or more at a time where more humans exist on Earth than ever before. It’s going to happen eventually, but probably not for somewhere around 100,000 years.

While you should absolutely go out and enjoy this unprecedentedly dim sight, as Betelgeuse is only ~36% as bright as it was a year ago, you must keep in mind that its current brightness variations are due to processes in its outermost layers alone, and have nothing to do with its core. Betelgeuse might go supernova at any time, but if it does, its correlation with this recent dimming event will be due to pure coincidence. What happens in the core doesn’t make it to the surface fast enough to give us any real, meaningful clues.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.