Representation matters. Meet five stellar women in physics who were unjustly denied their place in history.

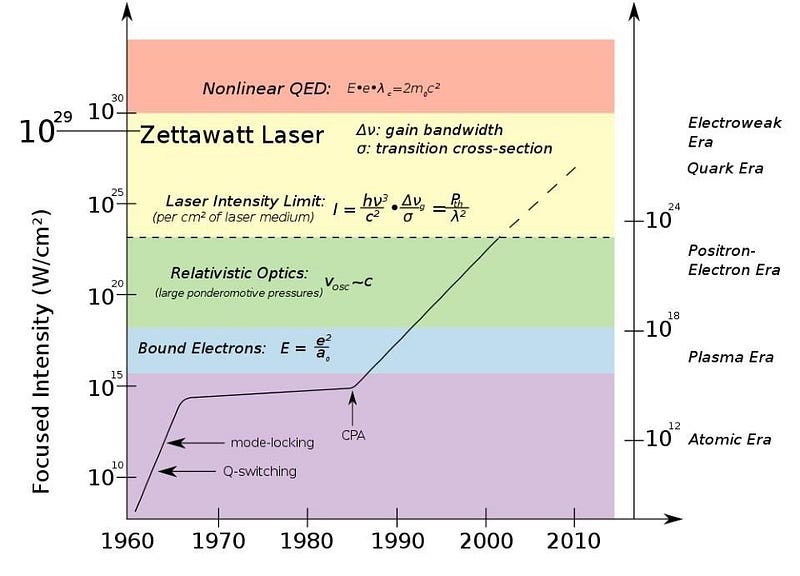

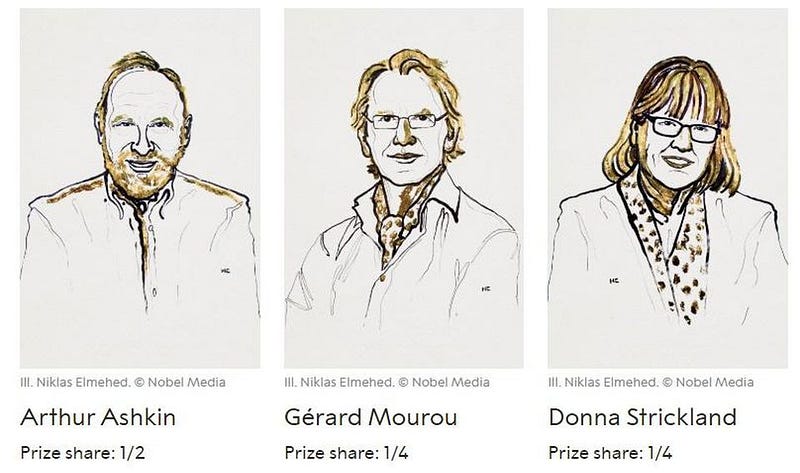

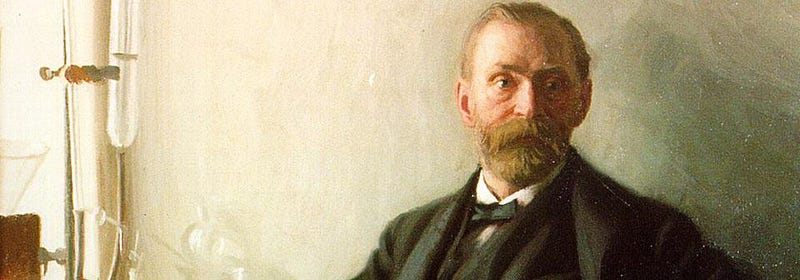

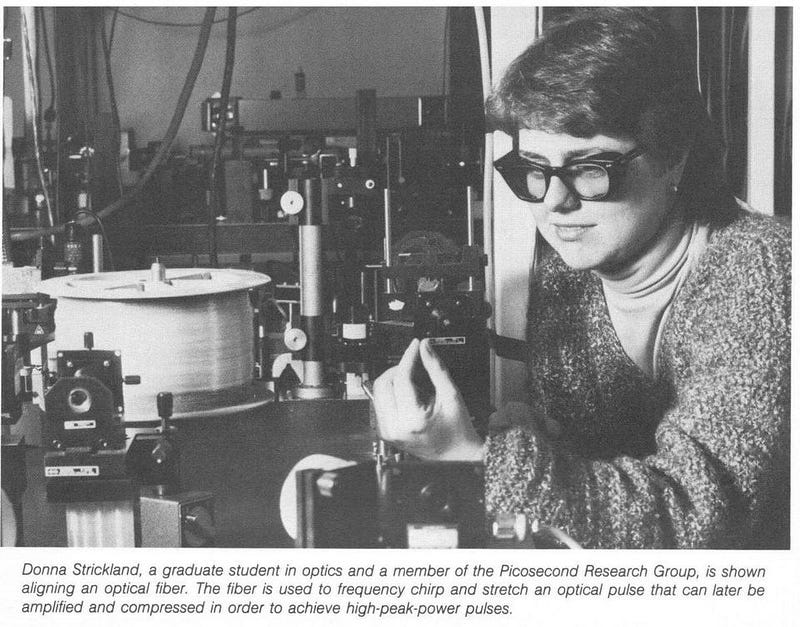

Nobel season is now over, with another year in the books of celebrating the scientists who pioneered some of the greatest advances in physics, chemistry, medicine and more. This year’s prize in physics, as it is in most years, was monumental. Awarded for the incredible advances made in laser science, 2018’s award celebrates the development of optical tweezersand ultra-short, ultra-powerful laser pulses.

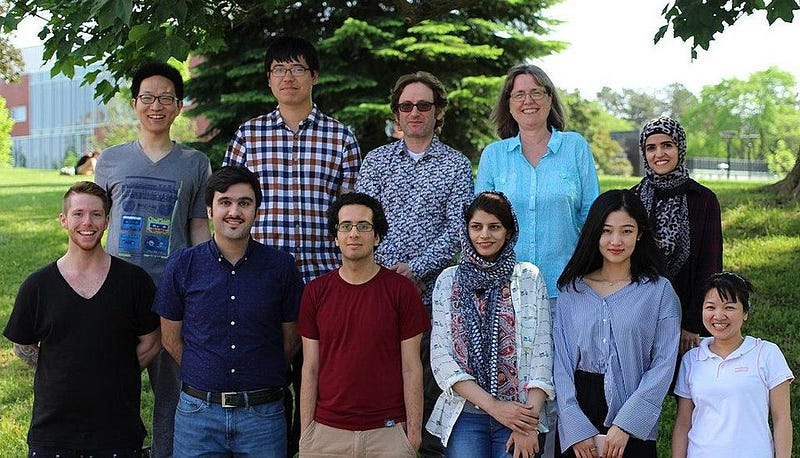

These breakthroughs have enabled countless new scientific and technological ideas to be brought to fruition, including LIGO, artificial guide stars, and lunar laser ranging on the science side and LASIK, laser etching and welding, and barcode readers on the technology side. But all of this has been overshadowed, rightfully so, by one important fact. For only the third time in history, one of the Nobel Prize in Physics’ recipients is a woman: Donna Strickland.

There is a long history, particularly in physics, of women going unrecognized for their achievements and contributions. Oftentimes, their advisors or collaborators — almost always more senior men in the field — have gotten the credit, as in the case of Maria Mitchell. In other instances, they themselves have languished in obscurity, unable to secure a viable career, while their contributions have gone on to revolutionize how science is done, exemplified by the case of Henrietta Leavitt.

Despite the overwhelming documentation and many egregious examples showcasing the fact that women have gone unrecognized despite their tremendous contributions, there are still many who argue that women are unfit in general to be good scientists, and use their lack of recognition, accolades, or Nobel Prizes as evidence for that absurd contention. It is a vicious circle that perpetuates ongoing gender inequality in a historically unfair system.

With her share of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics, however, Donna Strickland joins Marie Curie (1903) and Maria Goeppert-Mayer (1963) as the only three women in physics to be selected as Nobel Laureates.

Yet if there were any justice throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries, Strickland’s win might not be so notable for that fact alone. She was quoted, after learning of her award, as saying the following:

We need to celebrate women physicists because we’re out there, and maybe in time it will move forward. I’m honored to be one of those women.

But perhaps this is something that shouldn’t need to be said.

If the Nobel selection committee had awarded prizes based solely on the merits of scientific discovery, Strickland’s Nobel Prize wouldn’t merely mark her as the third woman to win the physics Nobel. Many deserving women have gone unrewarded over the years, even as men who were less deserving accumulated such accolades.

Here are five woman who were, in my estimation at least, the most unjustly, egregiously snubbed by the Nobel committee when it comes to being denied their rightful place in history for their scientific achievements in physics.

1.) Cecilia Payne, for the discovery of what stars are made of. We know today, that as matter gets heated, its electrons jump to higher energy levels, and with enough energy, they can become ionized. We know that stars exhibit different spectral features and absorption/emission lines, and this is dependent on the color of a star, which in turn is determined by the star’s surface temperature.

But none of that was known in 1925. In a stroke of brilliance in that year, synthesizing ideas and information from completely disparate fields, Cecilia Payne put those phenomena of temperature, color, and ionization together. In doing so, she was able to determine, based on the strength of the lines in stars of different types, what they were made of. While they contained the same elements as Earth, they had thousands of times as much helium and millions of times as much hydrogen. Despite her Ph.D. dissertation’s accolades, it was only her advisor, Henry Norris Russell, who was even nominated for the prize.

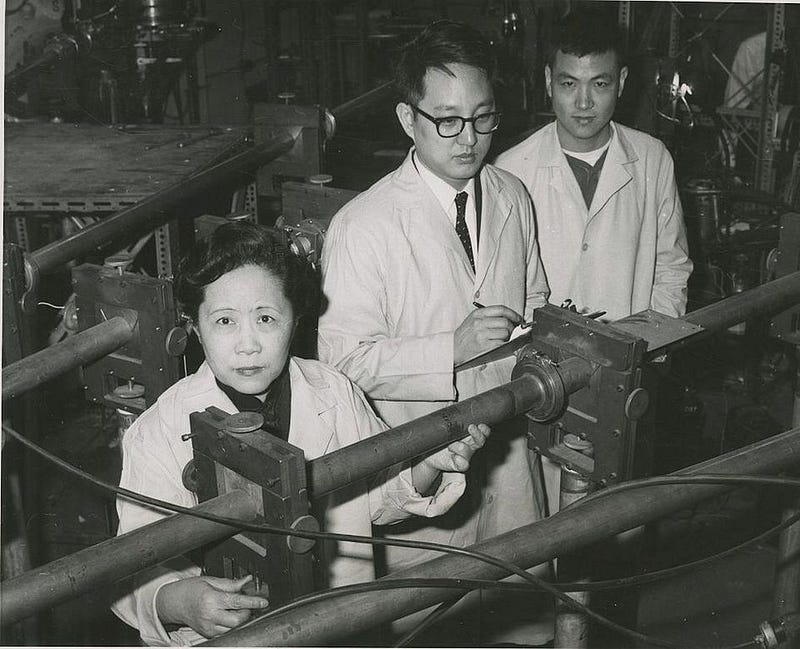

2.) Chien-Shiung Wu, for discovering the property of “handedness” of particles in the Universe. In the 1950s, physicists were just beginning to understand the fundamental properties of particles. Would spinning, decaying particles have a preferred direction to their decay products? If nature obeyed a mirror-symmetry (parity) law, they would. But theorists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang thought that under some conditions, they might not. Yet, as powerful as theoretical physics is, it’s only useful to the world when it’s put to the test. Only via experiment and observation can scientific truths about the Universe be revealed.

Chien-Shiung Wu set out to test this, by observing the radioactive decay of Cobalt-60 in the presence of a strong magnetic field. When the electrons (a decay product) exhibited a preferred direction, she directly showed that particles had an intrinsic handedness (and violated the parity symmetry) under the weak interactions. The 1957 Nobel went for exactly this discovery… to Lee and Yang, with Wu disgracefully omitted.

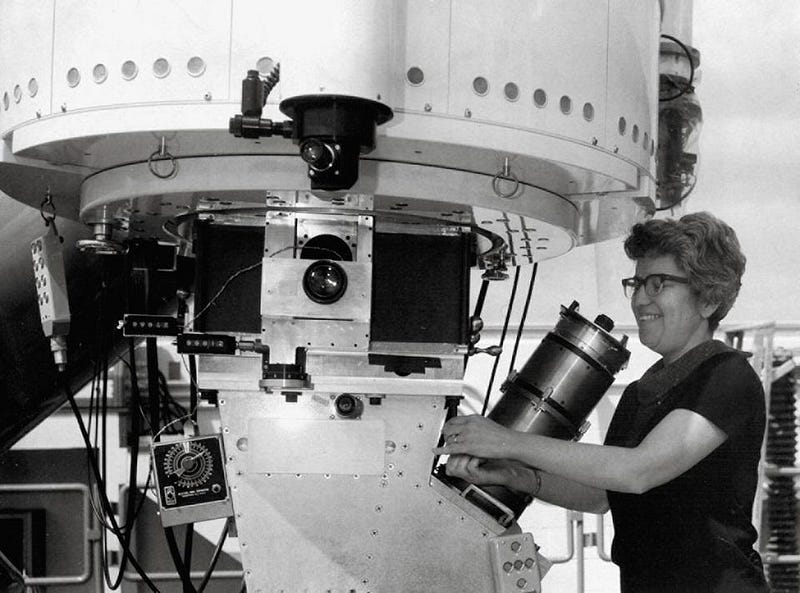

3.) Vera Rubin, for the co-discovery (with Kent Ford) of dark matter in galaxies. What makes up the Universe? If you asked this question 50 years ago, people would have pointed to atoms and subatomic particles as the answer. Surely, they could account for all the gravitation the Universe needed to exhibit, with even Fritz Zwicky’s galaxy clusters possibly having gas, dust, and plasma accounting for the missing mass. The science of Big Bang Nucleosynthesis and our ability to “weigh” the Universe through gravitational lensing and large-scale structure formation was still years away.

But Rubin (and Ford’s) work investigated how individual galaxies, starting with Andromeda, rotated at a variety of different radii. By observing a slew of individual galaxies and the way they rotated, a 100% normal matter Universe, under the current laws of gravity, was no longer possible. Rubin and Ford’s careful analysis of how individual galaxies rotated showed that there was more gravitation that normal matter could account for, bringing the dark matter problem into the mainstream. It is now accepted that dark matter is a major component of our Universe, but Rubin died in 2016, after waiting 45+ years for a Nobel that never came.

4.) Lise Meitner, for her discovery of nuclear fission. Meitner was a lifelong close collaborator of Otto Hahn, who was awarded the Nobel Prize (in Chemistry, although many Chemistry Nobels now go to fields we consider Physics, and vice versa) for the discovery of nuclear fission. Despite the fact that up to three people can share in the prize, Hahn was, quite unjustly, awarded this one all by himself in 1944. Meitner’s contributions were arguably even more important than Hahn’s, as she, not Hahn, was the one who did the important work of splitting the atom. On top of that, she had to endure the incredible injustice of working as a Jew in Nazi Germany in the 1930s, despite her imploring pleas falling on the deaf ears of Hahn, Heisenberg, and many others.

After fleeing Germany in 1938, Meitner continued correspondence with Hahn, guiding him through the critical steps in creating nuclear fission. Hahn, however, never included her as a coauthor, despite her invaluable contributions. Even though the titanic figure in physics, Niels Bohr himself, nominated both Meitner (first) and Hahn (second) for the Nobel, it was awarded to Hahn alone. When Meitner died, her tombstone was inscribed with the following simple sentence: “Lise Meitner: a physicist who never lost her humanity.”

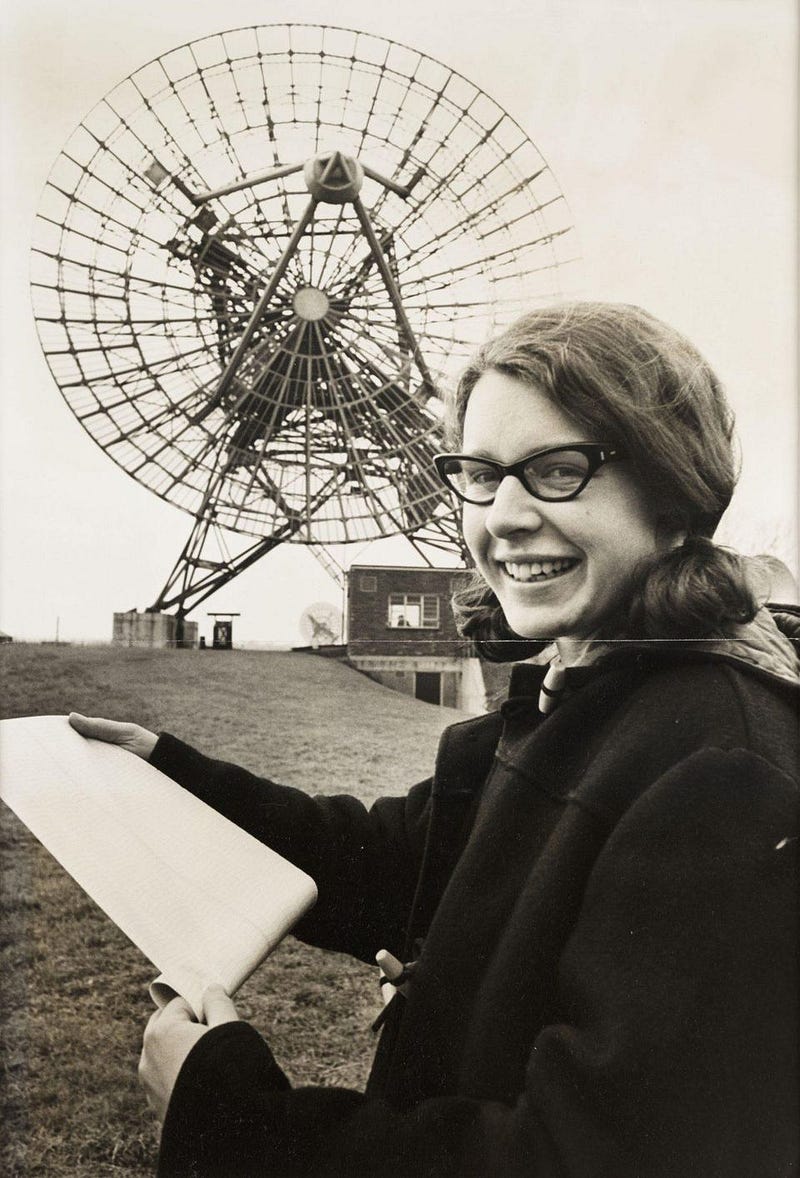

5.) Jocelyn Bell-Burnell, for her discovery of the first pulsar. Pulsars were predicted from supernovae as early as 1933, and the Nobel Prize was awarded for them in 1974 to Martin Ryle and Anthony Hewish. Yet neither Hewish nor Ryle themselves discovered the first pulsar, for which the prize was awarded. The person who did that work was Hewish’s student, Jocelyn Bell. She was the one who actually discovered the pulsar, and picked its interesting signal out as an object of particular significance.

Fred Hoyle and Thomas Gold, who put the final pieces together that Bell’s discovery was indeed a spinning, pulsing neutron star, argued that she should have been included on the prize. Despite her humility, asserting, “I believe it would demean Nobel Prizes if they were awarded to research students, except in very exceptional cases, and I do not believe this is one of them,” it is the one case I would assert that she’s wrong. Her work was exceptional, and her omission from the Nobel Prize was a mistake.

There will be many detractors out there who will claim, for a variety of reasons, that some or all of these women didn’t deserve a Nobel Prize for their work. After all, Payne and Bell-Burnell (and Strickland, for that matter) were only students when they did their research, for example, and many claim that Nobel Prizes shouldn’t go to someone who hasn’t “paid their dues” to the system, or that they were only acting on decisions made by their advisors. But that argument doesn’t hold any water, particularly in the cases of Payne (who did her work on her own) and Bell-Burnell (who discovered the key signal on her own.)

Besides, many Nobel Laureates throughout history were students when the did their prize-worthy research, including the physicists Lawrence Bragg (1915), Bob Schrieffer (1972), Brian Josephson (1973), Russell Hulse (1993), Douglas Osheroff (1996), Frank Wilczek (2004), and Konstantin Novoselov (2010).

The fact of the matter is that there is no concrete evidence that women are in any way inherently inferior to men when it comes to work in any of the sciences or any of their sub-fields. But there is overwhelming evidence for misogyny, sexism, and institutional bias that hinders their careers and fails to recognize them for their outstanding achievements. When you think of the Nobel Laureates in Physics and wonder why there are so few women, make sure you remember Cecilia Payne, Chien-Shiung Wu, Vera Rubin, Jocelyn Bell-Burnell, and Lise Meitner. The Nobel committee may have forgotten or overlooked their contributions until it was too late, but that doesn’t mean we have to. In all the sciences, we want the best, brightest, most capable, and hardest workers this world has to offer. Looking back on history with accurate eyes only serves to demonstrate how valuable, and yet undervalued, women in science have been.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.