The Untold Secret to Writing Your Dissertation

If you’re struggling with the final, most important obstacle separating you from your graduate degree, here’s how to make it happen!

“I spent every night until four in the morning on my dissertation, until I came to the point when I could not write another word, not even the next letter. I went to bed. Eight o’clock the next morning I was up writing again.” –Abraham Pais, physicist

You’ve been in graduate school for many years now, and you’ve come a long way. You’ve completed all of your coursework, formed your Ph.D. thesis committee, passed your preliminary/oral/qualifying examinations, and have done an awful lot of research along the way. There’s a glimmer of hope in your heart that maybe — just maybe — this will be your last year in graduate school.

You’ve probably even gotten some papers published along the way, with a handful of them (if you’re lucky) with you as the lead author! But there’s one more task you need to perform before you’re ready to defend in front of your committee: you must write that dissertation!

While there are many guides on how to do that, many of them are either jokes…

…or people grossly overstating the task in front of you. There are some very important things that go into a dissertation, but there are also some huge misconceptions about what a dissertation is supposed to be. What follows is my advice for anyone who’s reached that stage in their careers, on how to write a dissertation. (At least, as far as theoretical astrophysics goes, although I’m sure this is applicable to many other fields.)

First off, here is a list of what your Ph.D. dissertation is not:

- It is not the definitive work on whatever your primary research topic is.

- It is not going to settle long-standing arguments in your field.

- It is not the most important piece of research or writing you’ll ever undertake.

- And finally, it is very likely not even a document that anyone outside of your committee (with the exception of a few good friends, and possibly your grandmother) will ever read.

You must accept number 4 before you’re ready to write, otherwise you run the risk of becoming a perfectionist about a document that — seriously — practically no one is going to read!!!

What is a Ph.D. dissertation, then?

Quite simply, it’s your way of proving to your committee that you are a competent scientist in your own right, capable of standing on your own two feet as a scientist, researcher, and academic. It is where you demonstrate the following:

- That you are capable of making original, valuable contributions in an active field of research.

- That you are aware of and informed about the broad landscape of your field, the background and currently competing work being done on your specific sub-field, and that your professional opinions are well-informed and backed up by your knowledge and legitimate reasoning.

- That the body of work you submit in your dissertation is comprehensive enough to merit a Ph.D.

- And, perhaps most importantly, that you are ready to go off and continue your research (if you so choose) without the guidance of your mentor(s).

The first, second, and fourth of these are things you must convince your committee of during your defense; the third, however, is something that must speak for itself within your written dissertation.

And that’s why the most important thing you can do is to just crank it out. What you may not realize is that 75% of your dissertation is already done, you just need to take advantage of it!

What do I mean? I mean don’t reinvent the wheel!

Let me explain.

You’ve already written/published some papers, and you’re very likely at least part-way through some more projects that may or may not be completed by time you’re ready to graduate. Well, guess what?

That, right there, is most of your dissertation!

Let’s say you’ll have four papers completed by time you graduate, and another two projects that you’ve done significant work on, but that won’t be completed by graduation. Those four papers that will be finished are chapters 2-5 of your dissertation, and those two unfinished projects are Appendix A and Appendix B.

That’s your work that you created, so be proud of it and don’t re-invent it!

Get your University’s unique template, learn how to format your work properly within it, and marvel at how close you are! Here’s what you have to actually write, now, in order to graduate:

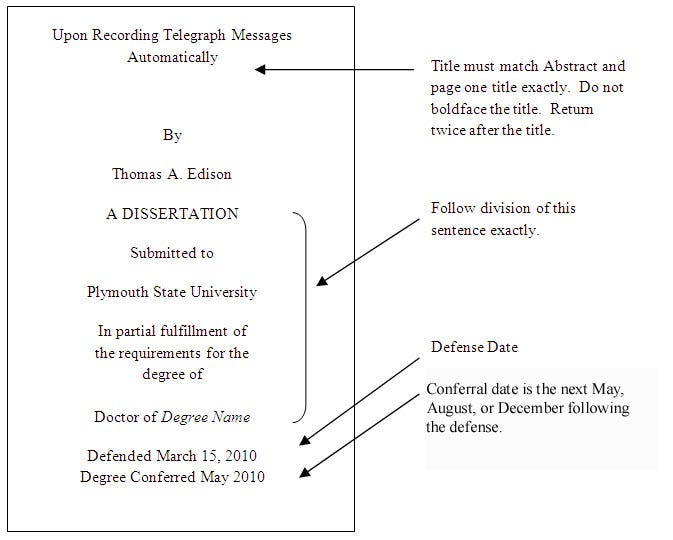

- Your title. This is important, and it needs to tie together all of the (likely) very different papers and topics you wrote on into one unified idea. “Topics in Physics” won’t cut it here, but “Cosmological Perturbations and Their Effects on the Universe: From Inflation to Acceleration” will do just fine.

- Your abstract. This is just two or three sentences introducing your field, followed by one sentence about each of your papers, and concluded with one or two sentences about future work.

- Your introductory chapter. This was — for me, at least — the hardest part. You need to put all of your original work in the context of your broad and specific fields of research. This means giving a broad (and well-referenced) overview of your sub-field, how it fits into the broad context of your field and why it’s important, and how your specific research has addressed some of these particular issues. It should be seamless to transition from the end of this chapter into your (only slightly tweaked) “middle chapters” of your dissertation.

- Your final chapter. This is a summary of what you’ve accomplished as well as a detailed discussion of what challenges remain in your field, with some detailed plans for future directions that your work is going to take you. This is where you include references to current, active work being done in your particular sub-fields of interest, and where you set up the motivation for your appendices.

The rest — acknowledgments, dedication, references, etc. — take practically no time or effort. But you must remember that the goal of your dissertation is not to change the world; it’s to finish it and to do a good enough job to graduate!

Once your written dissertation has been okayed by your committee, you’ll still have to defend, but this isn’t as worrisome as it might appear at first glance. You see, unless your advisor is so incompetent that they don’t care if you crash-and-burn, you won’t be allowed to defend unless everyone knows you’re prepared and ready to pass. After your defense, you’ll make your dissertation revisions, graduate, and it’s up to you whether you want to participate in the graduation ceremony or not; either way you get your diploma in the mail a few months later.

This isn’t the only way to write a dissertation, for what it’s worth. It’s just the smartest way to do it, and so that’s why it’s my advice. (It’s also advice that — for some reason — is rarely given by others.) Now you know the secret to writing a Ph.D. dissertation, so finish that thing up and graduate already!

An earlier version of this post originally appeared on the old Starts With A Bang blog at Scienceblogs.