The ‘Strong CP Problem’ Is The Most Underrated Puzzle In All Of Physics

In physics, anything that isn’t forbidden must occur. So why don’t the strong interactions violate CP-symmetry?

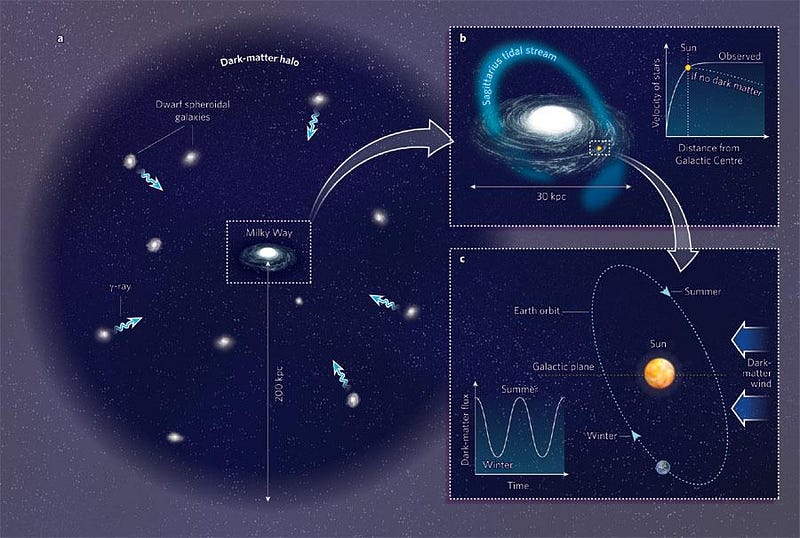

If you ask a physicist what the biggest unsolved problem facing the field today is, you’re likely to get a variety of answers. Some will point to the hierarchy problem, wondering why the masses of the Standard Model particles have the (small) values we observe. Others will ask about baryogenesis, asking why the Universe is filled with matter but not antimatter. Other popular answers are just as puzzling: dark matter, dark energy, quantum gravity, the origin of the Universe, and whether there’s an ultimate theory of everything for us to discover.

But one puzzle that never gets the attention it deserves has been known for nearly half a century: the strong CP problem. Unlike most of the problems that demand new physics that goes beyond the Standard Model, the strong CP problem is a problem with the Standard Model itself. Here’s the lowdown on a problem everyone should be paying more attention to.

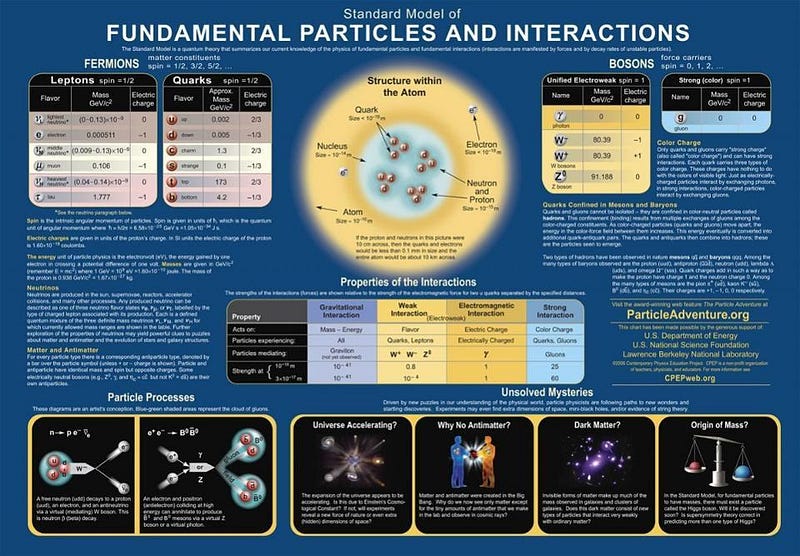

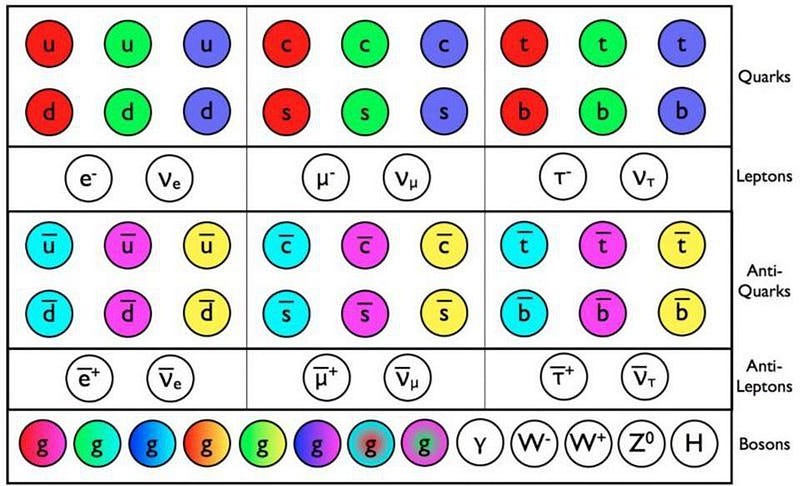

When most of us think of the Standard Model, we think about the fundamental particles that make up the Universe and the interactions that occur between them. On the particle side, we have the quarks and leptons, along with the force-carrying particles that govern the electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions.

There are six types of quarks (and antiquarks), each with electric and color charges, and six types of leptons (and anti-leptons), three of which have electric charges (like the electron and its heavier cousins) and three of which don’t (the neutrinos). But whereas the electromagnetic force only has one force-carrying particle associated with it (the photon), the weak nuclear force and the strong nuclear force have many: three gauge bosons (the W+, W- and Z) for the weak interaction and eight of them (the eight different gluons) for the strong interaction.

Why so many? This is where things get interesting. In most of the conventional mathematics we use, including most of the mathematics we use to model simple physical systems, all the operations are what we call commutative. Simply put, commutative means it doesn’t matter what order you do your operations in. 2 + 3 is the same as 3 + 2, and 5 * 8 is the same as 8 * 5; both are commutative.

But other things fundamentally don’t commute. For example, take your cellphone and hold it so that the screen is facing your face. Now, try doing each of the following two things:

- rotate the screen 90 degrees counterclockwise along the “depth” direction (so the screen is still facing your face), and then rotate it 90 degrees clockwise along the vertical axis (so the screen faces towards your left).

- Starting over, make the same two rotations but in the opposite order: rotate the screen 90 degrees clockwise along the vertical axis (so the screen faces left), and now rotate it 90 degrees counterclockwise along the “depth” direction (so the screen faces down).

The same two rotations, but in the opposite order, lead to a wildly different end result.

When it comes to the Standard Model, the interactions we use are a little more mathematically complicated than addition, multiplication, or even rotations, but the concept is the same. Instead of talking about whether a set of operations is commutative or non-commutative, we talk about whether the group (from mathematical group theory) describing these interactions is abelian or non-abelian, named after the great mathematician Niels Abel.

In the Standard Model, electromagnetism is simply abelian, while the nuclear forces, both weak and strong, are non-abelian. Instead of addition, multiplication, or rotations, the difference between abelian and non-abelian shows up in symmetries. Abelian theories should have interactions that are symmetric under:

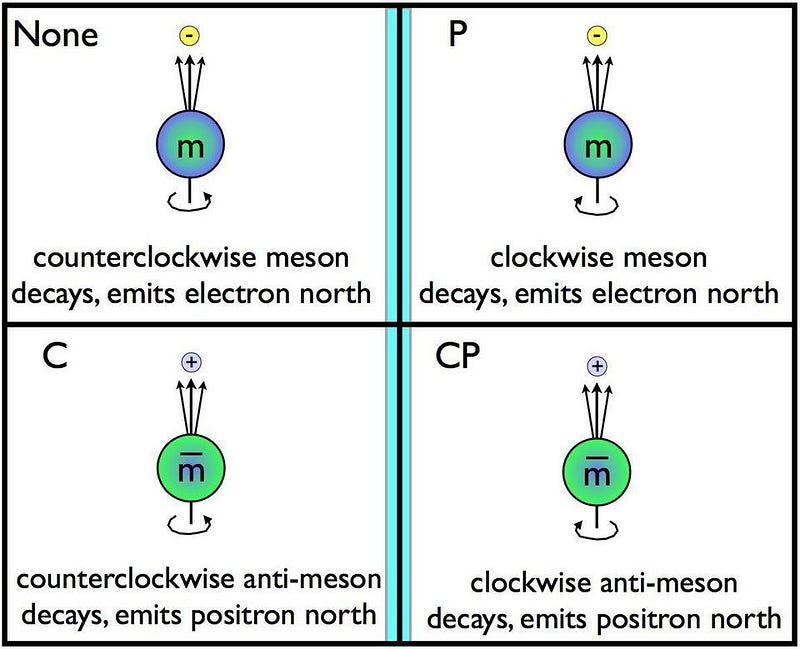

- C (charge conjugation), which replaces particles with antiparticles,

- P (parity), which replaces all the particles with their mirror-image counterparts,

- and T (time reversal), which replaces interactions going forwards in time with ones going backwards in time,

while non-abelian theories should show differences.

For the electromagnetic interactions, C, P, and T are all individually conserved, and are also conserved in any combination (CP, PT, CT, and CPT). For the weak interactions, C, P, and T have all been found to be violated individually, as are the combinations of any two (CP, PT, and CT) but not all three together (CPT).

This is where the problem comes in. In the Standard Model, certain interactions are forbidden, while others are allowed. For the electromagnetic interaction, violations of C, P, and T are all individually forbidden. For the weak and strong interactions, the violation of all three in tandem (CPT) is forbidden. But the combination of C and P together (CP), while allowed in both the weak and strong interactions, has only ever been seen in the weak interaction. The fact that it’s allowed in the strong interaction, but not seen, is the strong CP problem.

Way back in 1956, when writing about quantum physics, Murray Gell-Mann coined what is now known as the totalitarian principle: “Everything not forbidden is compulsory.” Although it’s often woefully misinterpreted, it’s 100% correct if we take it to mean that if there isn’t a conservation law forbidding an interaction from occurring, then there is a finite, non-zero probability that this interaction will occur.

In the weak interactions, CP violation occurs at approximately the 1-in-1,000 level, and perhaps one would naively expect that it occurs in the strong interactions at approximately the same level. Yet we’ve looked for CP violation extensively and to no avail. If it does occur, it’s suppressed by more than a factor of one billion (10⁹), something so surprising that it would be unscientific to simply chalk this up to chance alone.

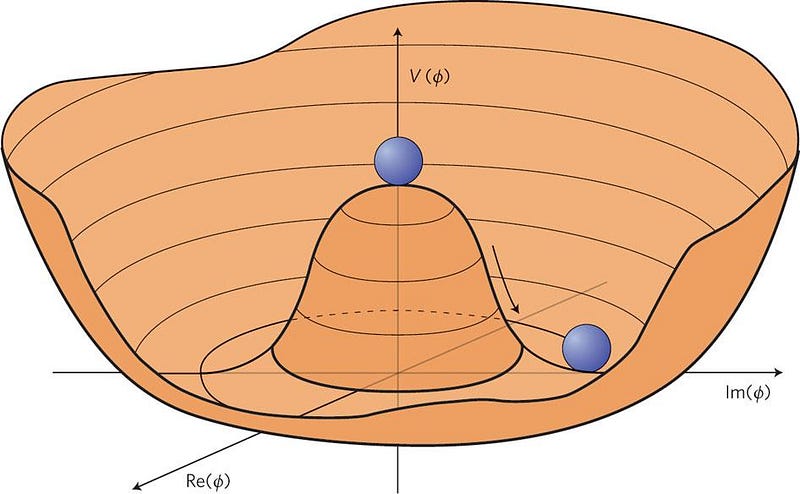

If you’ve been trained in theoretical physics, your first instinct would be to propose a new symmetry that suppresses CP-violating terms in the strong interactions, and indeed physicists Roberto Peccei and Helen Quinn first concocted such a symmetry in 1977. Like most theories, it hypothesizes a new parameter (in this case, a new scalar field) to solve the problem. But unlike many toy models, this one can be put to the test.

If Peccei and Quinn’s new idea were correct, it should predict the existence of a new particle: the axion. The axion should be extremely light, should have no charge, and should be extraordinarily abundant in number. It makes for a perfect dark matter candidate particle, in fact. And in 1983, theoretical physicist Pierre Sikivie* recognized that one of the consequences of such an axion would be that the right experiment could feasibly detect them right here in a terrestrial laboratory.

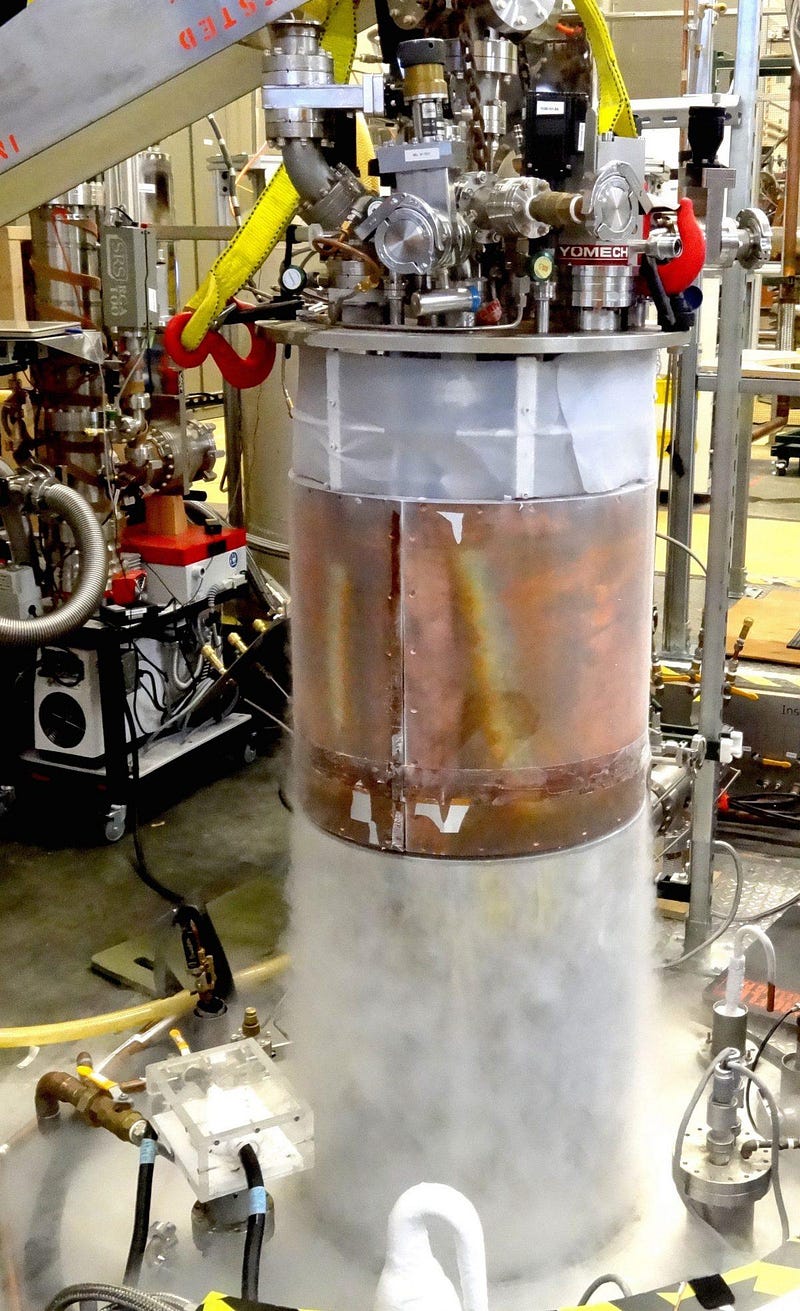

This marked the birth of what would become the Axion Dark Matter eXperiment (ADMX), which has been searching for axions for the past two decades. It has placed tremendously good constraints on the existence and properties of axions, ruling out the original formulation of Peccei and Quinn but leaving open the room that either an extended Peccei-Quinn symmetry or a number of quality alternatives could both solve the strong CP problem and lead to a compelling dark matter candidate.

As of 2019, no evidence for axions has been seen, but the constraints are better than ever and the experiment is presently being upgraded to search for numerous varieties of axion and axion-like particles. If even a fraction of the dark matter is made of such a particle, ADMX, leveraging (what I know as) a Sikivie cavity, will be the first to discover it directly.

Earlier this month, it was announced that Pierre Sikivie will be the 2020 recipient of the Sakurai Prize, one of the most prestigious awards in physics. Yet despite the theoretical predictions surrounding the axion, the search for its existence and the quest to measure its properties, it’s eminently possible that all of this is based on a compelling, beautiful, elegant, but non-physical idea.

The solution to the strong CP problem may not lie in a new symmetry akin to the one proposed by Peccei and Quinn, and axions (or axion-like particles) may not exist in our Universe at all. This is all the more reason to examine the Universe in every possible way at our technological disposal: in theoretical physics, there are a near-infinite number of possible solutions to any puzzle we can identify. Only through experiment and observation can we hope to discover which one applies to our Universe.

At almost every frontier in theoretical physics, scientists are struggling to explain what we observe. We don’t know what composes dark matter; we don’t know what’s responsible for dark energy; we don’t know how matter won out over antimatter in the early stages of the Universe. But the strong CP problem is different: it’s a puzzle not because of something we observe, but because of the observed absence of something that’s so thoroughly expected.

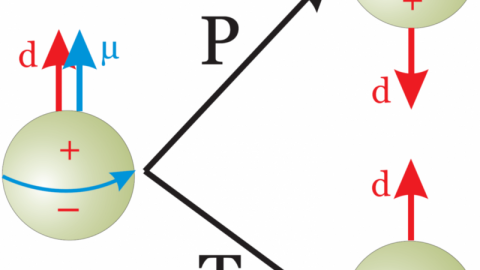

Why, in the strong interactions, do particles that decay match exactly the decays of antiparticles in a mirror-image configuration? Why does the neutron not have an electric dipole moment? Many alternative solutions to a new symmetry, such as one of the quarks being massless, are now ruled out. Does nature just exist this way, in defiance of our expectations?

Through the right developments in theoretical and experimental physics, and with a little help from nature, we just might find out.

* Author’s disclosure: Pierre Sikivie was the author’s professor and a member of his dissertation committee in graduate school during the early 2000s. Ethan Siegel claims no further conflict of interest.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.