We might have been spared the worst of Hurricane Matthew, but the underlying science is informative at any time!

“She didn’t even know what she’d do when she got back to New Orleans, but inside she felt a yearning to shove her hands in the dirt, to cling to the ground there, forever.” –Sarah Rae

The most destructive storms to occur on Earth — although they’re not limited to Earth — are hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones. Strong, sustained winds coupled with torrential, downpouring rain often brings with it severe flooding, incredible property damage capable of cresting 100 billion dollars and, quite frequently, death tolls that rise into the thousands. These storms all the same phenomenon, just given different names dependent on where they form on our world; generically, they’re known as tropical cyclones. While the big, sweeping, cloudy arms surrounding a quiet “eye” are familiar sights to even casual storm-watchers looking at a radar image or photo from space, the scientific ingredients are so few and so simple you might not believe it:

- Warm ocean water.

- Wind.

That’s it. Those are the only two ingredients you need, and that’s what gives you, at least on Earth, a tropical cyclone. Here’s how.

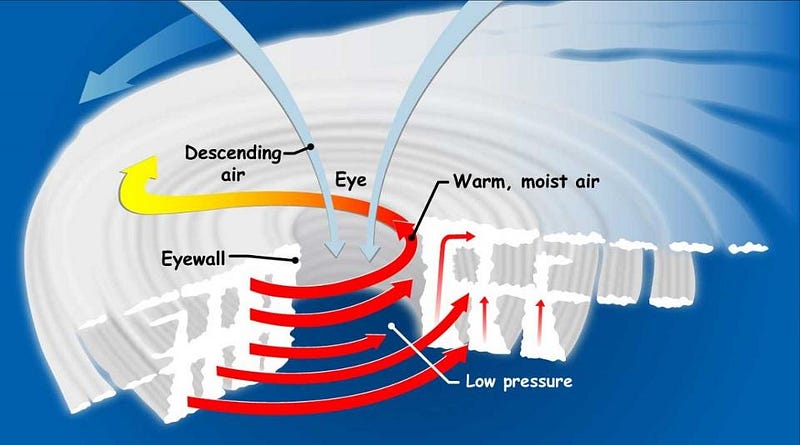

“Heat rises,” goes the saying, but that’s because the Earth’s atmosphere has a naturally built-in temperature gradient. The higher in the atmosphere you go, the farther away you get from the Earth’s surface: the best part of the Earth at absorbing, reflecting and re-radiating the Sun’s heat. The upper atmosphere is simply lower in temperature. If you’re over a body of warm water, a good amount of that water will be in the vapor phase in the air. When that air rises high enough and cools enough, the vapor gets pulled out of the gaseous phase and into the liquid phase. These tiny droplets, when enough of them meet in the same location, form clouds.

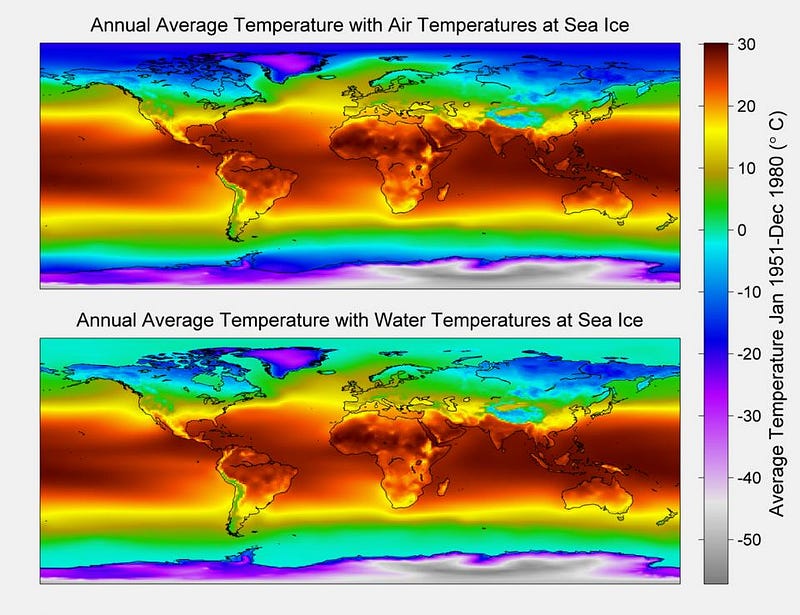

Clouds on their own, of course, won’t get you a tropical cyclone. But the warmer the ocean water is, the easier it is for that moisture-rich air to rise, cool, and provide ongoing fuel for a storm. In order to make a tropical cyclone, you need that water to be at least 80º F (27º C) for the first 50 meters (165 feet) of its depth. This is why tropical storms like hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones only form along the equatorial regions of the world; the water simply isn’t hot enough elsewhere given the other conditions of Earth.

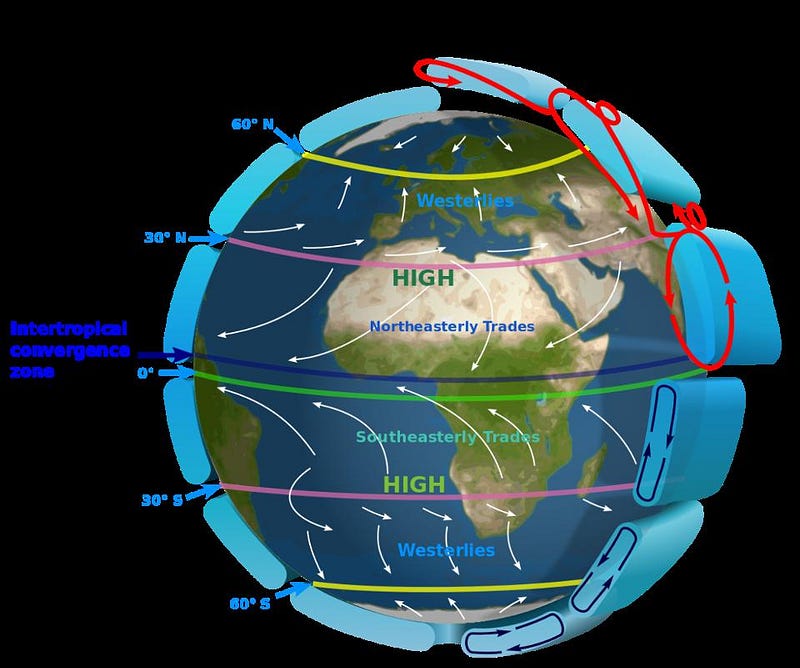

But unless you simply wanted a cloud-rich area over the ocean, you’d also need strong, sustained winds to make a tropical cyclone. Between about 30º N and 30º S of the equator, where the water is warm enough to give rise to tropical storms, the Earth’s prevailing winds circulate from east to west, with northern latitudes seeing winds that blow southwest and southern latitudes having winds that blow northwest.

Over the oceanic regions of these latitudes, the winds pass over the water’s surface. The warmer the surface water and the air just above the surface are, the faster the water evaporates, turning into water vapor in the atmosphere, and then rising. Just as before, the air and the vapor within it cool as the air rises, and eventually the vapor condenses back into thick clouds. These cumulonimbus clouds (or, more commonly, rain clouds) will “stack” on top of one another, rising higher and higher, creating a tropical disturbance.

Rising warm air is pulled into the column of clouds, while the air at the top cools and becomes unstable, and tries to sink again. But the cooling water vapor releases heat, making the cloud-tops warmer, raising the air pressure and causing winds to blow outwards from the center. Finally, the cool air can fall, but this low-pressure area makes it easy for the water at the surface to evaporate and rise, creating more clouds and a larger rising, stacking area. As winds in the column start to spin faster and faster, a tropical depression, tropical storm or even a full-fledged tropical cyclone (i.e., a hurricane) can form.

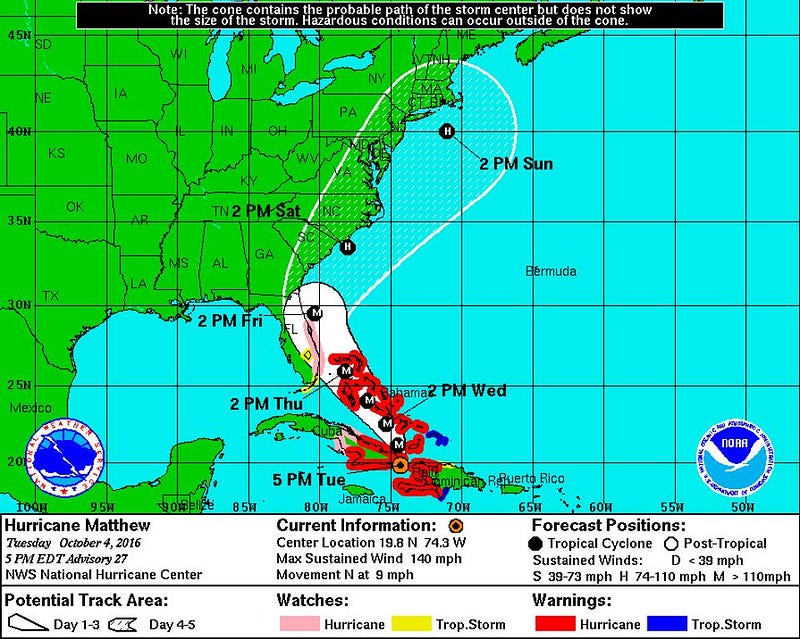

So long as they remain over warm water, tropical depressions, storms or cyclones can gain in strength, making landfall all that much more dangerous. In the worst-case scenarios, a storm can either remain stationary right on a coastal area for a long time, or it can move along a coastal region, constantly being fed by the ocean waters as it does so. Check out the difference between the real-time wind map of the United States today and the wind map as it was when Hurricane Sandy made landfall in 2012.

Forbes contributor and meteorologist Marshall Shepherd has been producing some excellent pieces about Hurricane Matthew, whose projected path right now projects to take it directly up the Atlantic coast of the United States.

The science of hurricanes might be absolutely fascinating, but as with all things, knowing how it works and being ready for its consequences are two very different things. Be safe over the coming week, and be aware that despite the uncertainties, it’s never a bad idea to be prepared for the potential worst case.

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!