The Pillars Of Creation Haven’t Been Destroyed, After All

Images taken 20 years apart show the rate of evaporation, and they’ll take much more than mere thousands of years to destroy.

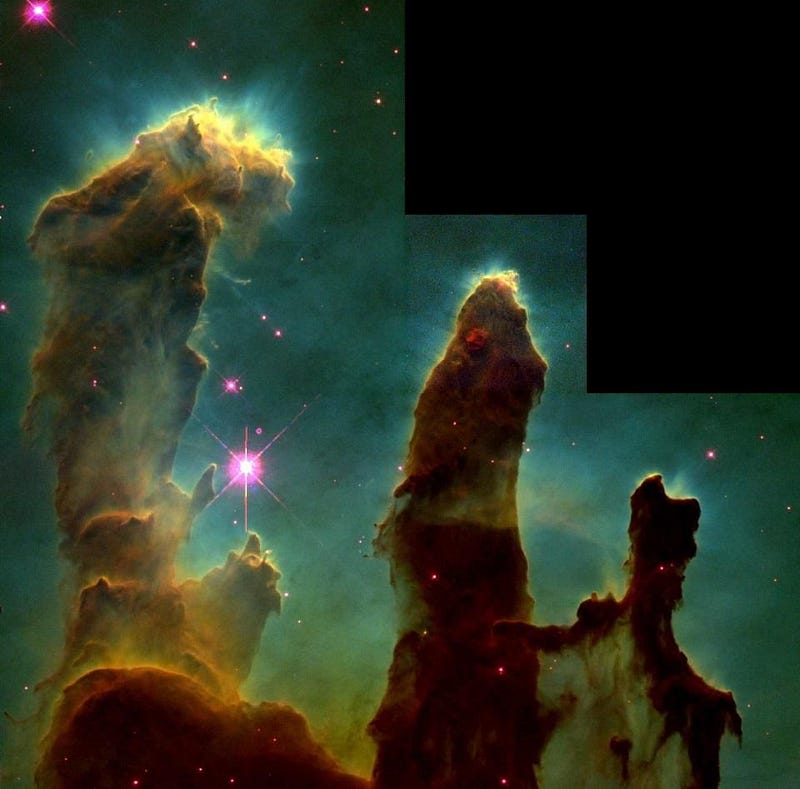

In 1995, the Hubble Space Telescope snapped one of the most iconic images of all-time: the famed “Pillars of Creation” in the Eagle Nebula. One of the galaxy’s closest and most productive regions of active star formation, these pillars represent what’s left of the neutral gas that powers the creation of these new stars. But new stars aren’t just a cosmic signpost of creation; they also bring destruction with them. When you form new stars, a fraction of them will be massive enough to go supernova, with these catastrophic explosions rapidly burning off and expelling the gas around them. Others will burn fantastically hot, evaporating this gas more slowly. What we’re seeing, inside this nebula, is a mix of these two processes. Years ago, a NASA study claimed that a supernova recently occurred inside, and that the pillars were already destroyed. Now, we’ve learned that was in error, and they’ll likely remain for hundreds of thousands of years before slowly evaporating away.

At 7,000 light years away, the Eagle Nebula is one of the night sky’s most accessible and spectacular nebulae. It was discovered back in 1745, and shortly thereafter was recognized to be an active star-forming region, as the surefire signature of ionized hydrogen was seen in abundance. A large cluster of newborn stars can be found inside, consisting of over 8,000 stars, which is the primary cause of the nebula’s shape. These stars, burning bright, emit copious amounts of ultraviolet light, which effectively ionizes and boils off the neutral gas. Inside the remaining globules, a three-way race is occurring between:

- gravity, which is working to pull the gas onto new clumps, protostars, and newborn stars, forming and growing them,

- the external stars, which are working to shrink and boil off the gas from the exterior,

- and from the internal stars, where the hot ones and potential supernovae expel the gas and stop the newborn stars from forming or growing further.

When the initial, iconic, 1995 Hubble image of the Pillars of Creation was first published, it represented the first time that these evaporating globules, replete with new stars inside, was imaged in such detail. From the details at the edges of the pillars, as well as the light appearing to stream out from the inside, we knew there was much more than mere reflection going on: there were newborn stars inside. Certainly, with large numbers of O-type stars nearby, including one that was identified to be at least 80 times the mass of the Sun, there were bound to be supernovae in this nebula’s future, if not its present. Owing to the capabilities of other space telescopes to see outside the visible light spectrum, scientists sought to find out whether there was evidence for a recent, catastrophic explosion inside.

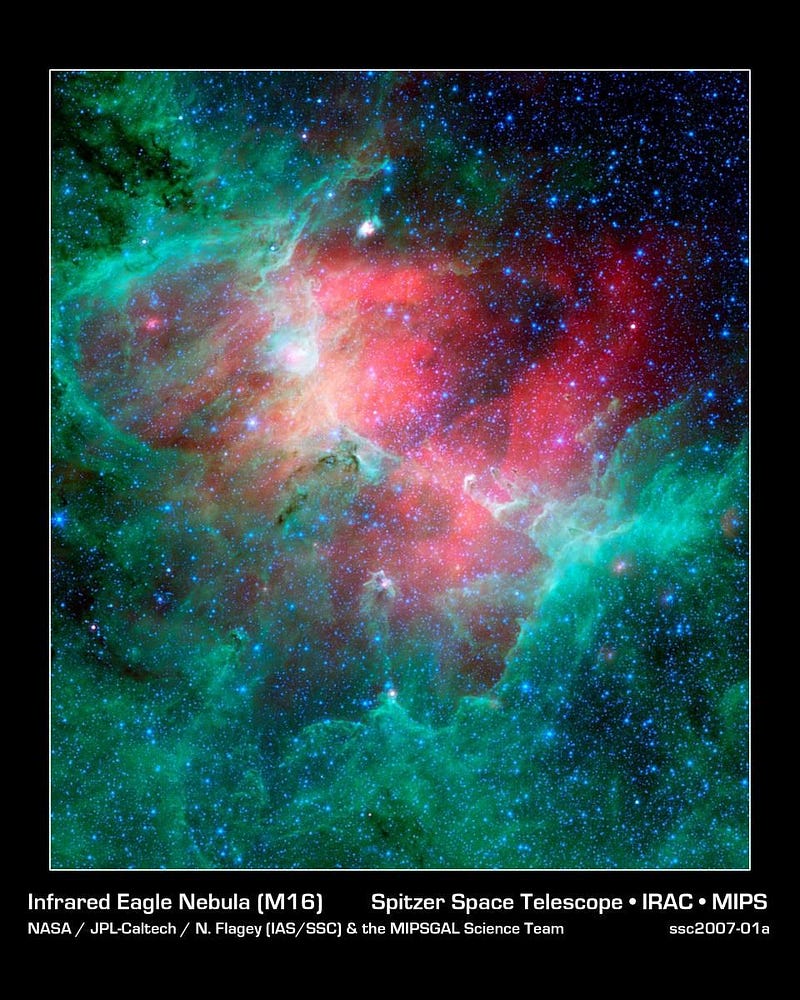

In 2007, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, observing in the infrared portion of the spectrum, showcased dust that was far warmer than expected. In particular, the red color in the image above was suggestive of not only new stars, but of a recent supernova that occurred either inside or behind the pillars themselves, warming the surrounding dust. Early speculation was that this supernova occurred some 8,000 years ago, and based on the propagation of the explosion, should have destroyed the pillars entirely over the ensuing millennia. Some contended that the pillars were already gone, and that the visual evidence was already on its way. It’s only the fact that there’s a 7,000 year light-travel time that’s prevented us from seeing it already.

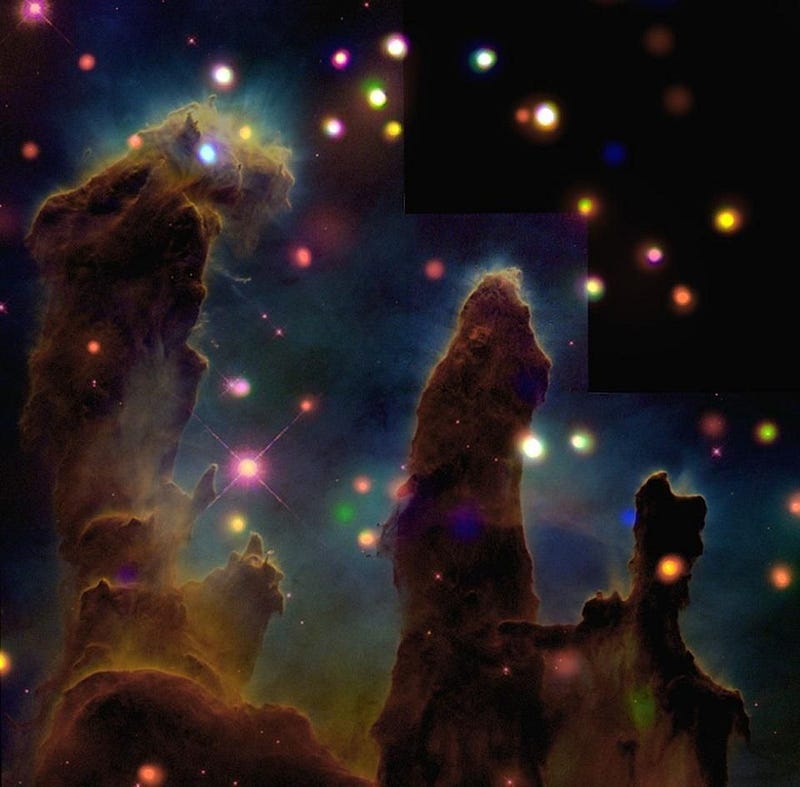

When we viewed these pillars in the X-ray, owing to NASA’s Chandra X-ray observatory, we were able to identify the presence of new stars inside and behind the pillars themselves. These X-ray emitting sources were consistent with massive stars, many of which are massive enough to go supernovae. If you see loaded explosives everywhere you look, it makes sense to conclude that evidence of a past explosion is, in fact, exactly that. Perhaps these pillars were already gone.

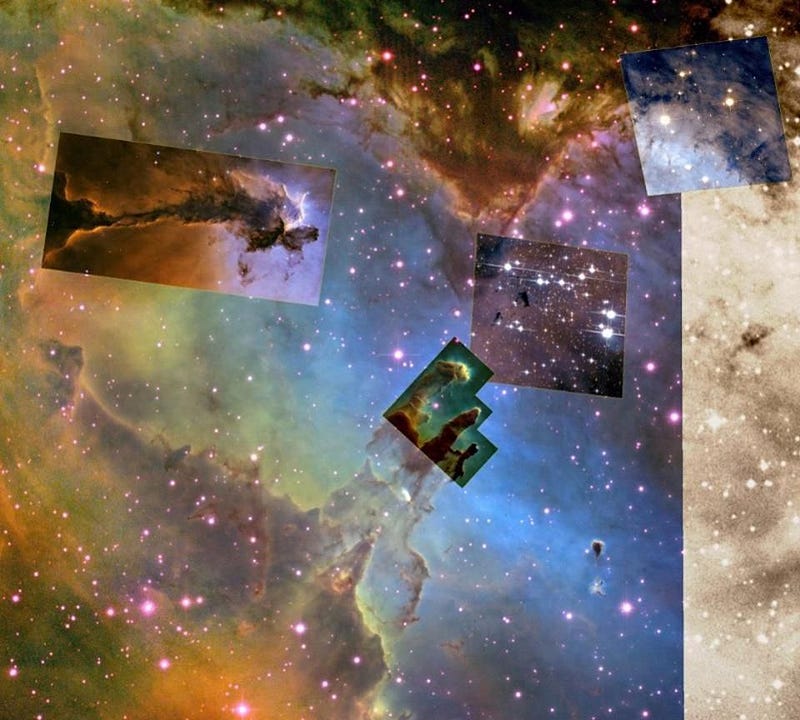

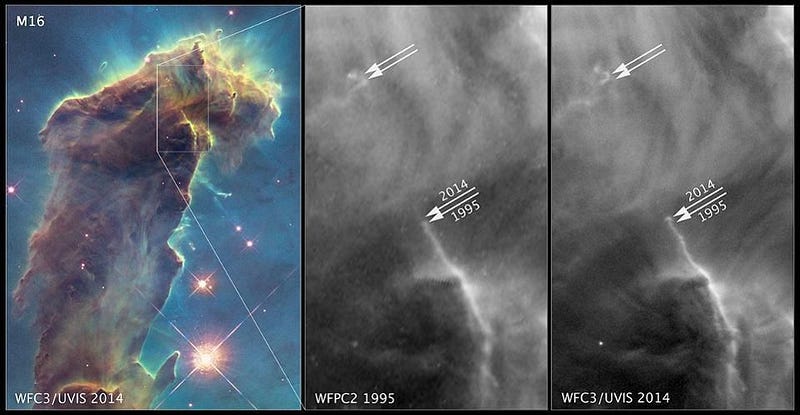

But in 2015, to celebrate Hubble’s 25th anniversary in space, NASA revisited these pillars, and the 20 year baseline between the original 1995 image and the new 2015 one provided insights that strongly refuted the already-destroyed pillars theory.

The 20-year follow-up showcased not only features that couldn’t be seen before, such as additional details, greater wavelength coverage, and a larger field of view. But the greatest and most important advance is the fact that the 20-year baseline allowed us to view changes over time. In the tip of the largest pillar, for example, we were able to not only identify an ejected jet, but to track the extent of its changes. With the incredible resolution of Hubble, we could determine that the size of it, over that additional time, expanded by an extra 100 billion kilometers: 1000 times the Earth-Sun distance, meaning that the stream is moving at 200 km/s.

Most importantly, however, is that unlike when the 1995 image was taken, the more modern data that was taken came when Hubble had a new, advanced camera installed on it. This included not only the same visible-light range that the old WFPC2 camera had, but a new slew of infrared filters that went out to double the maximum wavelength of the prior, old image. Owing to this, we were able to look “through” the pillars themselves, to the stars behind them. And, perhaps more importantly, to the evaporating gas that’s being burned off by the stars and cataclysmic events contained therein.

Highlighted in blue, above, we can see that it’s the incoming starlight that’s doing the burning off, and that there’s no evidence of a nearby, recent supernova at all. The Spitzer data, as far as we can tell, was assigned an incorrect interpretation. What we can also do, however, is measure and quantify the rate-of-evaporation of these pillars, from both internal and external radiation combined. Changes between the images indicate that the pillars are still intact today, even though the light we’re seeing came from 7,000 years ago.

Moreover, the best evidence for changes comes at the base of the pillars, indicating an evaporation time on the order of between 100,000 and 1,000,000 years. The idea that the pillars have already been destroyed has been demonstrated not to be true. It’s one of the great hopes of science that any controversial claims will be laid to rest by more and better data, and this is one situation where that has paid off in spades. Not only has there not been a supernova that’s in the process of destroying the pillars, but the pillars themselves should be robust for a long time to come.

In fact, the latest Hubble data has enabled us to do something that would’ve been unimaginable with the 1995 data alone: to construct a 3D model of the pillars in space! What might appear to be three pillars standing tall in the same plane are actually pieces of a far more interesting structure, where new stars are being formed inside a multitude of spires that have a surprising amount of depth to them. Though the pillars themselves are only around 5 light years long, apiece, they are separated by more than that amount in the “depth” dimension.

It’s always possible that one of these massive stars will reach the end of their lives at any moment, going supernova and taking out a large portion of one of these major internal structures that make up the Eagle Nebula. As it stands right now, however, it looks like evaporation, not a cataclysmic explosion, is the cause of the changes going on in the nebula right now. Unless there’s a catastrophe in the near future, it will be the slow process of evaporation that dominates, eventually blowing the gas off and revealing the newborn stars within. The Pillars of Creation won’t be around forever, but all signs point to them still being there today. They haven’t been destroyed, and as the light continues to arrive over the next thousands of years, we’ll see them shrink only slowly, likely for hundreds of thousands of years to come.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.