The One Science Lesson Every American Adult Can Learn From Greta Thunberg

She’s not a scientist, an expert, or even an adult. But she’s got one good lesson to teach us all.

Like most people on Earth, Greta Thunberg is not a climate scientist. She has no formal scientific training of any type, nor does she possess any expert-level knowledge or expert-level skills in this regime. She has never worked on the problems or puzzles facing environmental scientists, atmospheric scientists, geophysicists, solar physicists, climatologists, meteorologists, or Earth scientists.

Like most of us, she is an ordinary citizen of the world: with strong beliefs, opinions, and political inclinations. But unlike most of us, Greta has shown a willingness to do what most of us refuse to do. Her starting point for how to move forward in the world is to begin from a position of scientific consensus. While most of us prefer to be given the facts and trust that we, intelligent as we are, can figure it out for ourselves, Greta recognizes the unparalleled value that scientific expertise brings to our world.

It’s true that there are many scientific conclusions that are only provisional, and that much of what we conclude is accurate today may be overturned by superior evidence in the future. The way science proceeds is by constantly re-evaluating your theories, ideas and hypotheses in the face of the ever-changing full suite of evidence. When the evidence contradicts the theory, the theory must be thrown out, modified, or otherwise revised.

But when the evidence lines up with the theory’s predictions, it provides confirmation and validation that we’re at least on a thoroughly reasonable path. This is how scientists in all fields, whenever they’re doing good science, proceed. It applies to any issue you can imagine, from vaccinations to fluoridation to evolution to dark matter to the Big Bang and more. And yes, it also applies to global warming and, more generally, to the field of climate science.

Colloquially, in non-scientific parlance, most of us might view the idea of consensus the same way Margaret Thatcher did: as a dirty word that describes abandoning our principles to achieve a politically expedient agreement. As Thatcher put it,

Consensus: “The process of abandoning all beliefs, principles, values, and policies in search of something in which no one believes, but to which no one objects; the process of avoiding the very issues that have to be solved, merely because you cannot get agreement on the way ahead. What great cause would have been fought and won under the banner: ‘I stand for consensus?’”

But to a scientist, consensus means something very different. Consensus is not a compromise; it’s not a fact-free matter of opinion; and it’s certainly not immune to challenge. Instead, the consensus is our starting point: the point that all reasonable scientists in a field can agree on.

Scientific consensus is not some made-up, subjective term that you can manufacture. It’s vital that the consensus be challenged continuously, and contrarian ideas are always welcome to make concrete predictions that differ from the mainstream ones; if the decisive data comes in and conflicts with the consensus positions, perhaps the contrarian idea may even rise to replace the current consensus.

It’s necessary, if we care about science progressing, that we subject every assumption and conclusion we’ve drawn to meet the challenges posed by new data, methods, and observations. In this regard, scientists who challenge the consensus play an enormous role in probing at the cracks in any prevailing theory. Most often, the theory holds up, but every so often, a revision or even an overhaul is necessary, marking a significant shift in any scientific field.

Most people recognize that these things are true when it comes to science. What Greta Thunberg has to teach us, that most people (perhaps even most scientists) fail to grasp, is that the scientific expertise you learn in the process of becoming a scientist is what enables you to make informed judgments about the merits of various scientific assertions. And, if you care about achieving the most desirable outcome, you must accept the best science the world has to offer — the scientific consensus on an issue, where one exists — or you don’t deserve a seat at the table.

A scientific consensus doesn’t pop up overnight, or in places where there are legitimate scientific controversies with multiple, equally good explanations. It’s why every physicist agrees on what you’ll see when you perform a double-slit experiment (there is consensus), but physicists don’t agree on which interpretation of quantum mechanics is preferable (there is no consensus).

A consensus will only arise when a theory is good enough to make predictions that are robust, verified by multiple lines of evidence, backed up by a statistically significant amount of data, and where definitive observations have been taken that discern one particular theory’s predictions from the others.

It’s why General Relativity is the consensus theory of gravity, but also why we continue to challenge it with new observations in regimes where it hasn’t yet been tested.

It’s why evolution, via the mechanism of genetic mutation and natural selection, is the consensus theory on the origin of the species currently found on Earth.

It’s why vaccination and fluoridation are overwhelmingly recommended by public health experts as near-universal goods, while vitamins are only recommended for those with nutritional deficiencies.

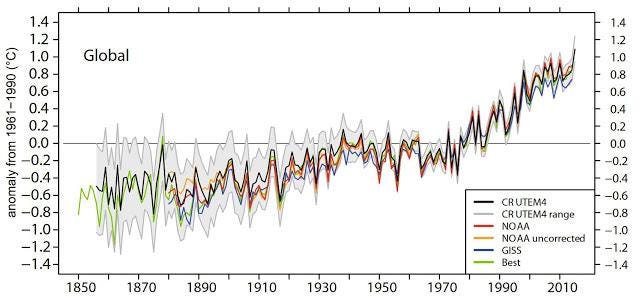

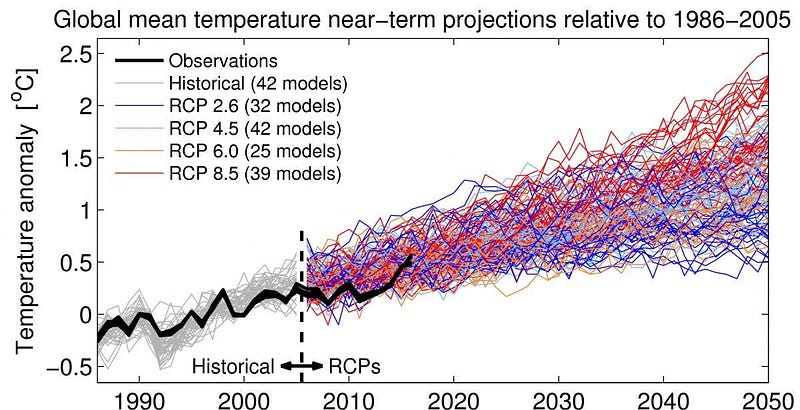

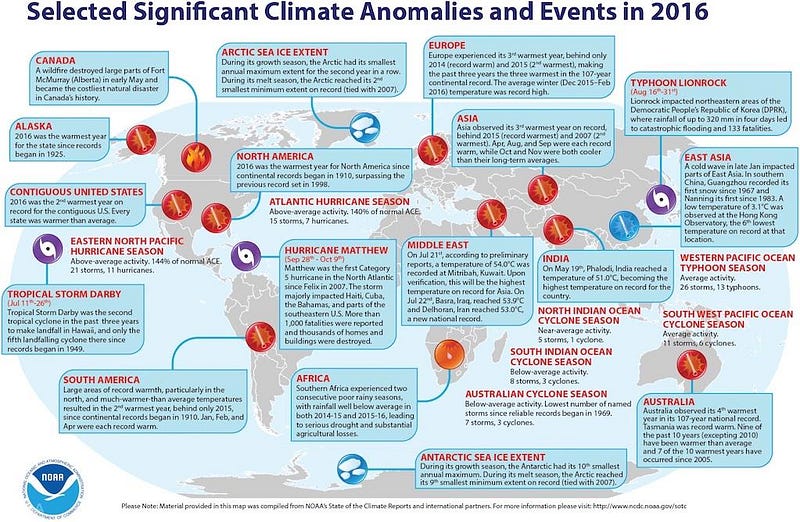

And it’s why, in the field of climate science, it is overwhelmingly accepted that the world is warming and human modification of our natural environment — largely through the burning of fossil fuels — is the primary cause. It is also part of the consensus that this warming is altering the climate, increasing the frequency and maximum severity of extreme weather events, and is disproportionately impacting coastal and sea-level regions.

The consensus position only includes those points we can confidently state are true. For example, there is an overwhelming consensus about certain features of climate models, but other features have large uncertainties which haven’t led to a consensus. But what has occurred, overwhelmingly, is that motivated groups, individuals and industries have engaged in a serious, sustained misinformation campaign, and it has been very persuasive.

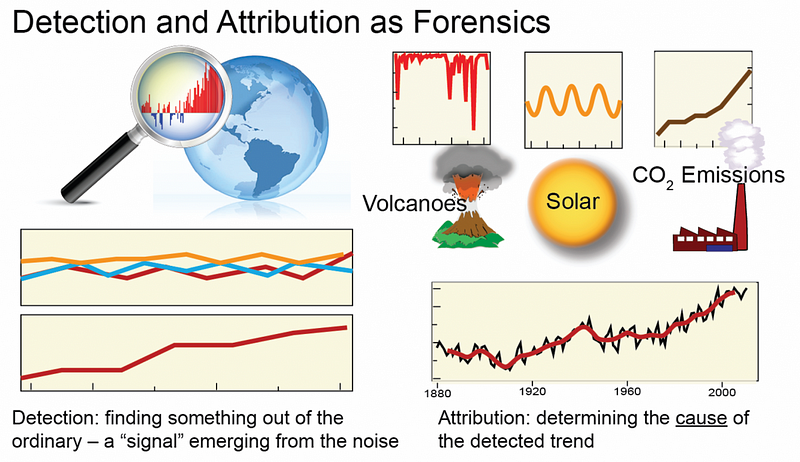

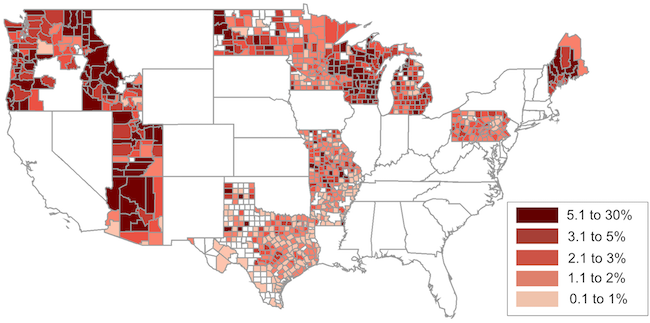

A survey from earlier this month shows that, among 28 surveyed countries, the United States of America ranks highest in the percentage of citizens who deny the existence of climate change. 6% of Americans deny that the climate is changing, even though earlier this decade the annual temperature record surpassed the 5-sigma statistical significance threshold: the gold standard in particle physics; for an environmental science result to cross that threshold is almost unheard of.

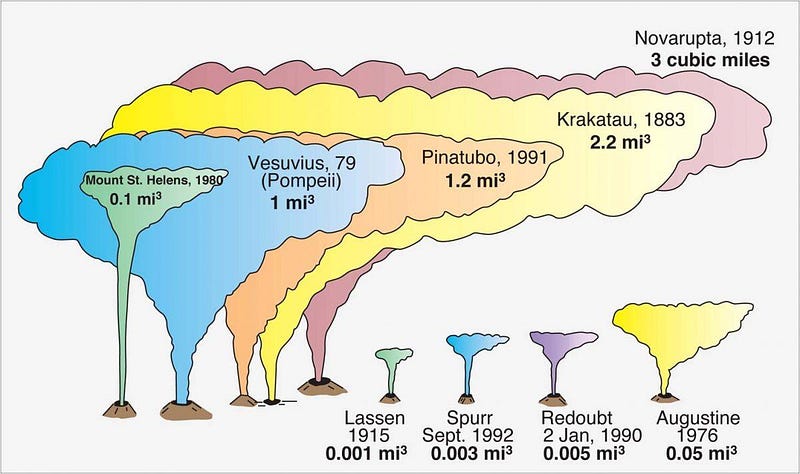

Moreover, another 9% deny that humans are responsible for climate change, even though the various contributing factors (the Sun, volcanoes, cloud cover and global dimming, etc.) have been well quantified.

What Greta Thunberg gets, and the important lesson she has for all of us, is this. The science has been unambiguous since the late 1980s: the Earth is warming, humans are the cause, and the only way to combat this is through large-scale action taken by our world’s governments. The largest contributors to the causes of climate change — the addition of greenhouse gases to our planet’s atmosphere — come from just a few dozen corporations. In particular, 71% of all the emissions from 1980 to 2015 come from just 100 companies, practically all of which are fossil fuel producers.

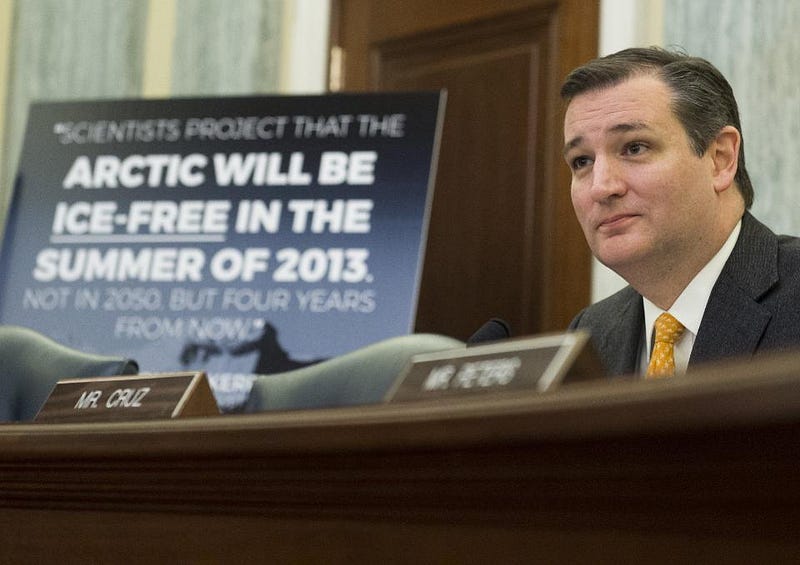

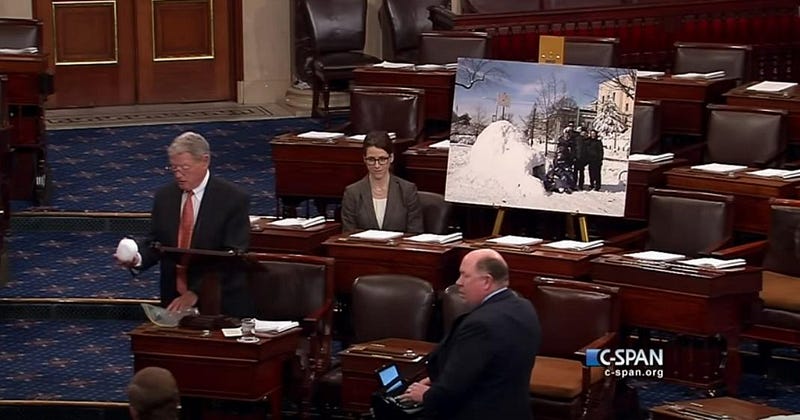

Yet our governments are failing us. They are instead misrepresenting the science and coming to the table dishonestly and disingenuously, planting red herrings to undermine the actual consensus, strawmanning and working to de-fund and devalue the existing knowledge on climate science, sowing doubt in places where there is none on scientific merits, and demanding party loyalty over reason and science.

It’s a free world and a free country, and no one can stop you from believing whatever you want. You can believe that vaccines cause autism, that the Earth is flat, that humans never walked on the Moon, and that global warming is a hoax. But if you believe any of those things, you are choosing an unsubstantiated and anti-science conspiracy that, when confronted with the actual evidence humanity possesses, doesn’t have a legitimate leg to stand on.

For decades, politicians have commanded scientists to stick to their science and not enter conversations about science and society. Yet we live in a world where some of the most powerful nations are governed by inherently anti-science attitudes. Science has already carried the day when it comes to global warming and climate change; now is the time to be an adult and address the real changes humanity has brought upon planet Earth.

There is an overwhelming scientific conclusion being ignored by the entire world. For decades, scientists have sounded the alarm, only to be met by a government that complains about the volume and tone of the alarm while ignoring the contents of the message. The time for arguing over whether this problem is real, severe, or our fault is long past.

It’s time for real action, and long past time to vote out any impostors that can’t get on board with the scientific consensus. Every one of us has a voice and a vote, and we cannot let these obstructionist tactics obscure the truth any longer. There’s a real problem here, and while fixing it will be a long-term endeavor, we all know where to start: by accepting the truth and considering solutions that address the scientifically legitimate issue at stake. If we can’t at least take that step, we’re dooming future generations to the worst possible climate scenario. We’re capable of preventing that outcome. Whether we do or not depends entirely on what we do next.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.