Your opinions about a large number of complex scientific issues are probably wrong. That’s why we have science.

In 2016, an Italian virologist named Roberto Burioni was invited to appear on television alongside two celebrities: Red Ronnie (a DJ) and actress Eleonora Brigliadori. Near the end of the program, the host turned to Burioni for the first time. His response is now legendary:

“The Earth is round, gasoline is flammable, and vaccines are safe and effective. All the rest are dangerous lies.”

Over the past few months, the COVID-19 pandemic has spread around the world, aided and abetted by millions upon millions of people — including many of the most powerful politicians in the world — who failed to heed the warnings of public health and scientific experts. But this is not a new problem. People deny scientific facts all the time when facing up to them is the more fearsome option. But science is real whether we accept it or not, and denying it harms the whole of human society.

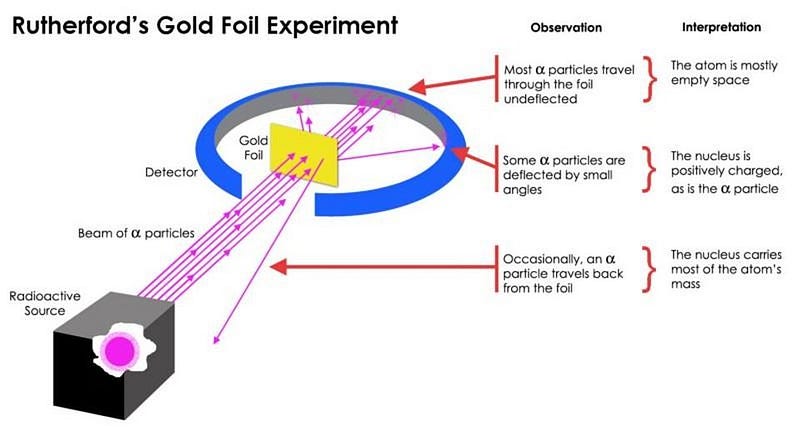

Science is the most valuable tool we have for exploring the natural world and Universe around us. If we want to figure out how any physical system works, all we have to do is investigate it scientifically: by asking it the right questions about itself. That means performing experiments, measurements, and observations — under the right, relevant, controlled conditions — to reveal the answers.

It’s true that science is always a work-in-progress. Sometimes, new data comes along to overturn the previously prevailing consensus. Sometimes, flaws are found in the data, methods, or analysis of what we thought we had understood, changing the conclusions. And sometimes, effects that had previously been neglected turn out to be important, altering what we thought we knew.

Science isn’t just a body of facts, it’s a process, and part of that process necessarily involves reaching preliminary, provisional conclusions that may later turn out to be wrong. But the only thing that has ever overturned a previously held scientific consensus is additional scientific inquiry: i.e., more and better science. Moreover, the more we learn about the natural world, the smaller and more esoteric those changes and effects tend to generally be.

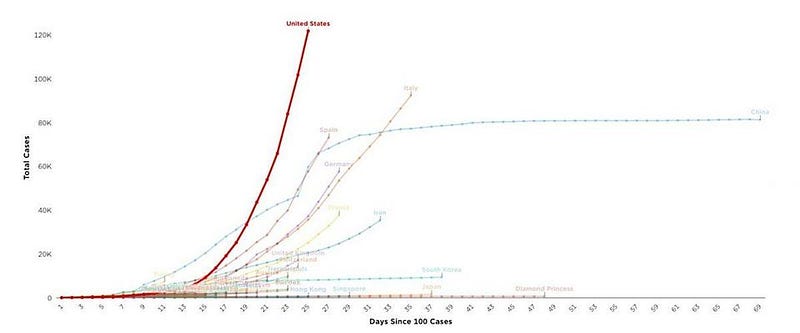

Right now, we are seeing the consequences unfold, worldwide, of ignoring the science of epidemiology, virology, disease ecology, and public health. The current COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, as of today, has infected a minimum of 850,000 people already, with over 40,000 confirmed deaths. Even today, many are failing to practice social (i.e., physical) distancing, convinced that the scientific conclusions reached by the field are mistaken.

Of course, the physical and biological sciences will continue to do what they do irrespective of human opinion. Politics may be a team-based sport while science most certainly is not. But a society that embraces scientific thinking — and incorporates the best scientific evidence and knowledge into their public policies — is a society where we’re all better off. COVID-19 is only the most immediate example of science denialism, but it’s one where the consequences are the most clear-cut, particularly in the short term.

Science, on the whole, is the best guide we have for predicting what will happen in the future. If we understand any system successfully, we can understand at least the basics of what consequences our actions (or inactions) will have. They say that the first stage of grief is often denial, often accompanied by anger, and yet when it comes to a scientific or health issue, denial, particularly in the early stages, is the worst thing we can collectively engage in if we don’t want to exacerbate the problem.

Scientific consensus isn’t something that’s arrived at lightly. Consensus is not a compromise; it’s not a matter of opinion; it’s not immune to challenge. Instead, consensus is a fact-based starting point for any reasonable discussion among professionals: it’s the point where the overwhelming majority of professionals are all in agreement with one another.

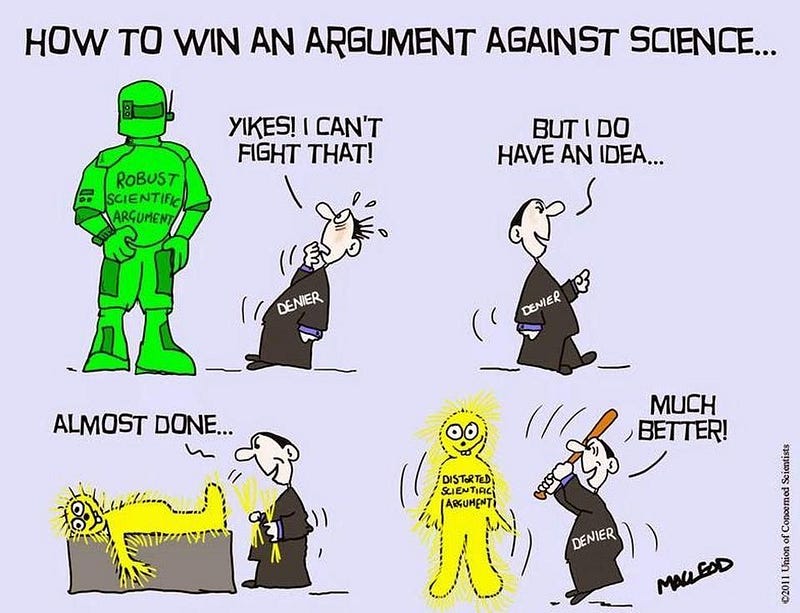

There are often legitimate challenges to any scientific consensus, but the legitimate ones always come from a purely scientific point-of-view. Typically, there’s a new piece of evidence that’s come to light that conflicts with the prevailing consensus, and more and better science is required to put that into context with the rest of the field. Most frequently, the consensus holds up. It’s only on rare occasions that a true scientific revolution occurs.

And yet, most people hold at least one belief, often based on anecdotal or (perceived) personal experience, that wholly conflicts with the available scientific evidence. The flu vaccine, available every year or two, would prevent tens of thousands of deaths annually if vaccination rates were high, and yet the percentage of Americans who get the flu vaccine annually has dropped to a decades-long low for the most recent year available: below 40%.

Anti-vaccination sentiment continues to remain a problem in the country, even as preventable, dangerous, and highly contagious diseases like the measles have returned. Measles, in particular, is so contagious that it requires that approximately 95% of the population have immunity against it to prevent its spread to vulnerable, necessarily unvaccinated populations. And yet, denial of the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, along with a long-debunked conspiracy that they cause autism, remains widespread.

This is one dangerous type of science denialism: denying the safety or effectiveness of something that has been robustly established to be safe and effective. This includes examples such as:

- 5G wireless technology, which poses no health risks to humans in the doses that even those with the greatest exposure endure,

- fluoridated drinking water, which reduces cavities and bone fractures in the recommended dosages while not increasing any ill effects until much higher doses are reached,

- glyphosate (RoundUp), which not only doesn’t cause cancer, but the only environmental problem it causes is the development of glyphosate-resistant weeds.

It’s very easy to make people afraid of something that they themselves don’t understand well, but the science is very clear on these issues. The societal benefits of a vaccinated population, of widespread and available high-speed internet, of reduced cavities, and of improved crop yields are not disputed by any mainstream scientific source.

However, the other major form of science denialism is even more potentially hazardous: denying the real risks and dangers that science has established. COVID-19 is a dangerous, deadly, and contagious disease, and can be combatted through a variety of medical and social interventions. Yet, even today (March 31, 2020, at the time of this writing) many people are publicly denying the well-established dangers that the novel coronavirus presents.

Examples of this type of denialism include:

- denying the causal link between HIV and AIDS,

- denying the link between tobacco and lung cancer,

- denying the link between head trauma and chronic traumatic encephalopathy,

- denying the link between safety belts in automobiles and a reduction in traffic fatalities,

- denying the need to evacuate an at-risk area during a hurricane warning,

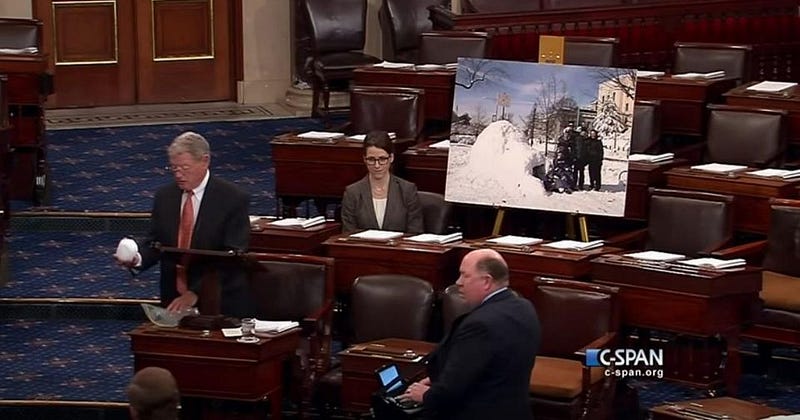

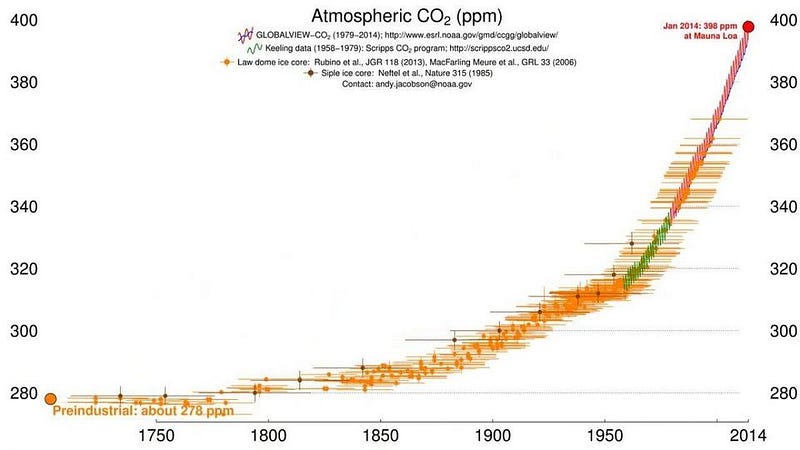

- and, perhaps most famously, denying the link between CO2 emissions and both global warming and global climate change.

Science denialism is not just someone glorifying an obviously ignorant position, like a flat Earth or declaring that the Moon landings were a hoax. It’s a common form of self-deception, where many of us think (either consciously or subconsciously) that we won’t need to reckon with an inconvenient aspect of reality if we reject it. But that’s never what actually happens. Instead, we harm ourselves, others, and society as a whole through our selfish self-delusions.

And it is a delusion to think that we, as non-expert individuals, know more than the experts do. As I’ve written previously,

All of the solutions that require learning, incorporating new information, changing our minds, or re-evaluating our prior positions in the face of new evidence have something in common: they take effort. They require us to admit our own limitations; they require humility. And they require a willingness to abandon our preconceptions when the evidence demands that we do. The alternative is to live a contrarian life where you’re actively harming society.

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have widespread consequences for the entire world on a wide variety of fronts: social, economic, and political all included. But the biggest lesson of all should be the scientific one: when we ignore the best recommendations of science, our entire society suffers unnecessarily. There’s the old saying that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and the dangerous lie that harms all of society is the idea that the ounce of prevention is expendable. In many cases, such as COVID-19, the prevention is so necessary exactly because there is no cure.

There are many challenges we all face in our day-to-day lives that consume us, and it’s a challenge to plan ahead weeks or months in advance, much less years, decades, or centuries, which is where the effects of global warming and climate change are most severe. But the science is real regardless of our beliefs and irrespective of our actions, and listening to it is one thing we can all do to improve not only our own lives, but to serve the public good.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.