Star Trek: Discovery’s Greatest Science Moments Rethink What It Means To Be Alive

What if alien life — or even intelligence — don’t look like what we’re searching for?

When the original Star Trek premiered, it was revolutionary for depicting sentient, intelligent species other than humans, living and serving side-by-side with us, along with the same rights, variations, and conflicts that plague our human existence. When The Next Generation came out, it went a step further, as a multitude of aliens and unconventional life forms appeared, along with artificial ones, such as androids, nanites, and exocomps. The questions of “what does it mean to be alive” as well as “what does it mean to be intelligent” were reckoned with, even if a clear conclusion was never reached. With Star Trek: Discovery’s conflicts and technologies — warp drive, spore drive, cloaking devices, holograms, etc. — getting all the attention, it’s easy to miss the biggest question of all: what does it mean to be alive and intelligent?

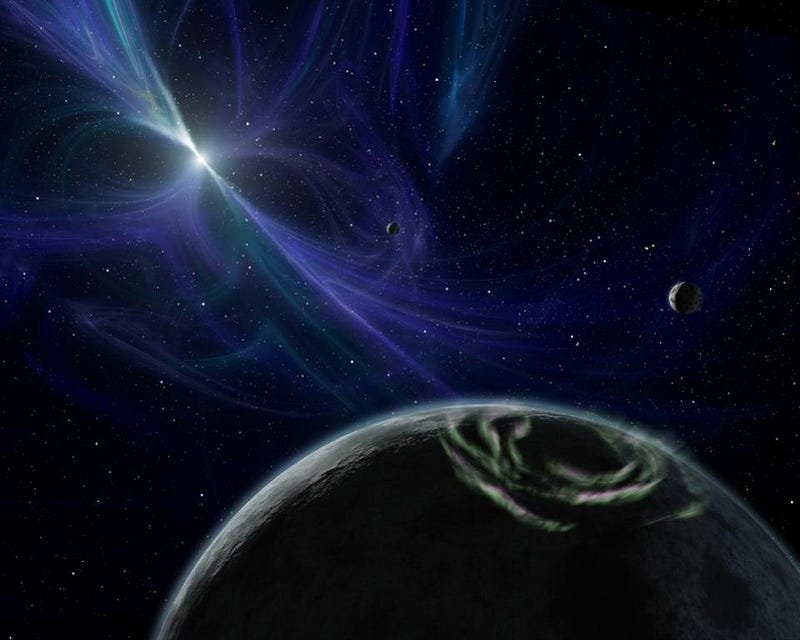

This question speaks to the very core of our curiosity about space. Once humanity had the spectacular realization that every star in the night sky was a Sun like our own, the possibilities were too great to ignore. Were there planets around them? Were any of them like Earth? Did they have the right ingredients for life on them? The right conditions? And if so, did life arise there? Was it like life here? Did any of it rise to become complex, multicellular, differentiated, intelligent, tool-using, or even spacefaring? And, if so, could we contact them, communicate with them, or even meet, exchange knowledge, and interact with them?

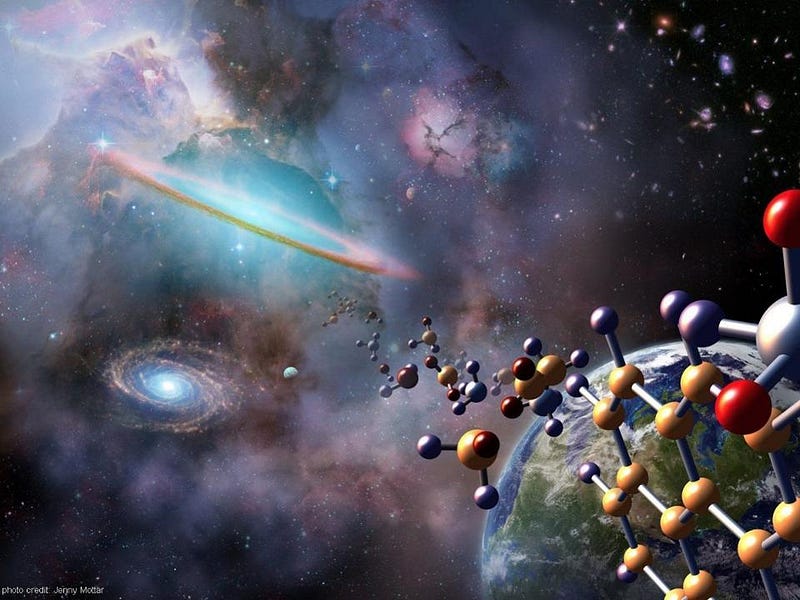

With the advances of modern astronomy, astrophysics, and our planet-hunting capabilities, we’ve learned that there are likely some two trillion galaxies in the Universe, each one with hundreds of billions of stars, with practically every one of those containing multiple planets. Many of those worlds are similar in size to Earth, with the right ingredients and at the right distance from their stars for liquid water, carbon-rich organic molecules, and potentially, life. While we haven’t yet found another instance of life beyond our planet, the possibilities is not only tantalizing, it’s everywhere we look.

It’s been a possibility that Star Trek has spoken to many times in a variety of ways. While most of the famous aliens encountered by Federation crews have been humanoid — including Klingons, Vulcans, Romulans, Ferengi, and Cardassians — there have been notable exceptions. The vampire cloud of The Original Series, the crystalline entity of The Next Generation, the changelings of Deep Space 9 and many others have challenged our conventional notions of what intelligence or life might look like. Now that we’re in the late 2010s, science has advanced tremendously, and so has our imagination for what might be possible.

The ingredients for life and complex, organic molecules aren’t simply found on Earth-like worlds, but in interplanetary and interstellar space. Organic molecules are found in newly-formed stars; sugars, hydrocarbons, buckminsterfullerenes, and even ethyl formate (the molecule that gives raspberries their smell) are found in gas clouds in our galactic center; even asteroids and meteors in our Solar System contain not only the 20 amino acids involved in life processes on Earth, but more than 60 others that could, potentially, lead to life forms very different from what we recognize.

So while others are arguing about the timeline, the development of technology, who’s good and who’s evil, it’s important to not lose sight of the biggest advance that Star Trek: Discovery brings us: a new view on what intelligent life might look like. Actually, it’s brought us three new views that open our eyes to a type of wonder we might never have considered otherwise.

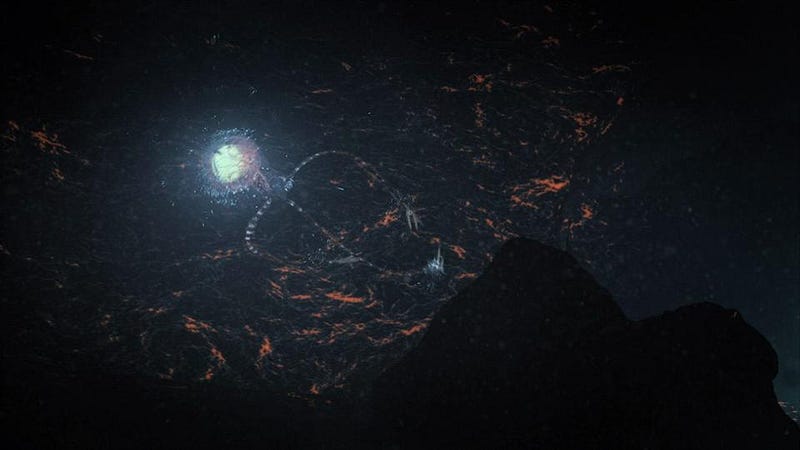

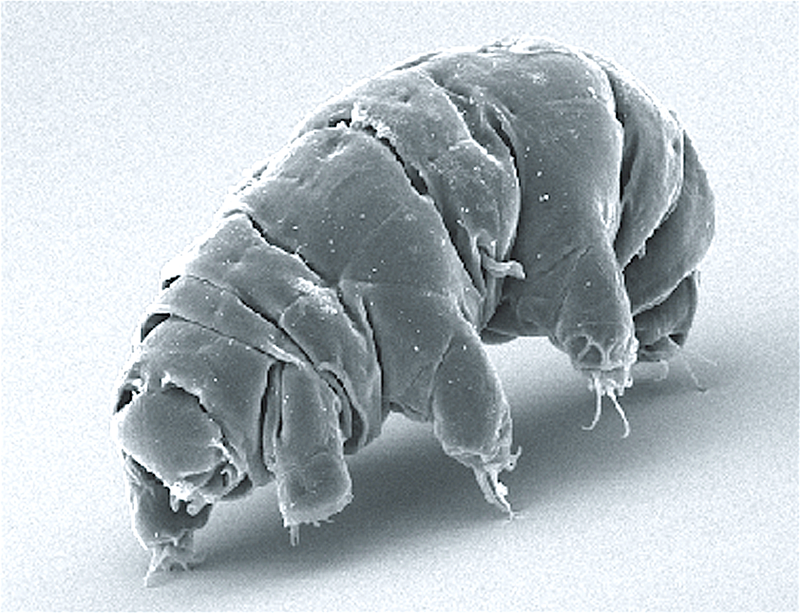

1.) The Space Tardigrade: there are tiny, microscopic “water-bears” here on Earth that can survive — if not thrive — in extreme environments. When plunged into the vacuum of space, they can expel all of the water from their bodies, losing 97% of their mass, and entering a state of suspended animation, where they can remain for years. Upon re-entering a hospitable environment, they revive and continue their activities, no worse for wear.

Star Trek: Discovery takes this idea one step further, as these macroscopic, intelligent tardigrades seem to feed off of an energy found in the depths of space itself. With no need to dehydrate or enter a state of suspended animation, these space tardigrades push the boundary of how we understand life to work, and challenges us to imagine a life form that’s unlike anything we know on Earth.

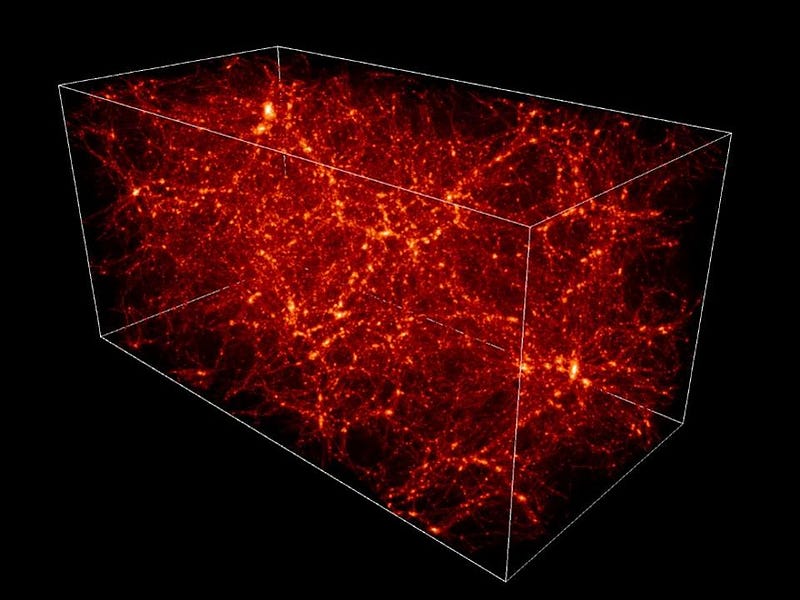

2.) The Mycelium Network: when you think of intelligent creatures, you probably think of large animals, like human beings. We have autonomy, a centralized processing center, and personalities unique to our own selves. But distributed intelligences, even across many trillions of organisms working together, could be a networked form of intelligent life distinct from what we normally consider. The mycelium network of fungal spores, spread throughout the galaxy and quantum entangled all across space, represents a unique take on what an intelligent organism could look like.

Loosely based on mycological networks found here on Earth, Star Trek: Discovery’s mycelium network fuses together many different ideas from physics and biology to create a new type of organism and a new type of intelligence. It might even make you wonder if the Universe, itself, could be alive? While there are many questions with unclear resolutions when it comes to an idea like the mycelium network, Star Trek deserves to be lauded for challenging what we think may be possible in this new way.

3.) The Pahvans: could a non-corporeal being, something that wasn’t even based on the concepts of cells (or even matter) somehow be alive? Going a step farther than any Star Trek incarnation has ever gone before, the Pahvan species brings up the possibility that extraterrestrial intelligence, when we encounter it, might be very easy to miss if we aren’t open-minded enough as to what it might look like. Yet all intelligence truly requires is a way to process, interpret, and deliver information, and the assumption that chemical-based life is the only way to do so is a bias we have because we are chemical-based life.

But that isn’t necessarily the case. There may be forms of matter or energy out there that we may never have considered, yet their reality is not dependent on whether we recognize them or not. Could there be electromagnetic intelligences out there? Dark matter-based life? A network of single-celled creatures acting as a more intelligent, less egotistical version of a human brain? The possibilities are astounding, if we dare to consider them.

Star Trek has always been a pioneering series for its ability to hold up a mirror to society in an advanced, near-utopian future, allowing us to address and think about our problems by providing us with a new perspective on them. When it comes to the very question of life itself, including what it means to be alive and/or intelligent, it’s extremely valuable to be aware of the assumptions we make when we think about what’s out there. One of the greatest scientific fears we should have is not that we’re alone in the Universe, but that the signals to recognize an alien intelligence have already been found, and our own biases have us overlooking what’s right in front of our faces.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.