“What goes up, must come down,” is an old saying that remains true for any object thrown or fired from Earth’s surface that fails to escape into space. Even a bullet, fired straight up at the maximum speed a gunpowder blast can accelerate it to, will never leave the lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere: our troposphere. A combination of gravity and air resistance will slow it down until it reaches a maximum height, whereupon it will fall back down to Earth’s surface.

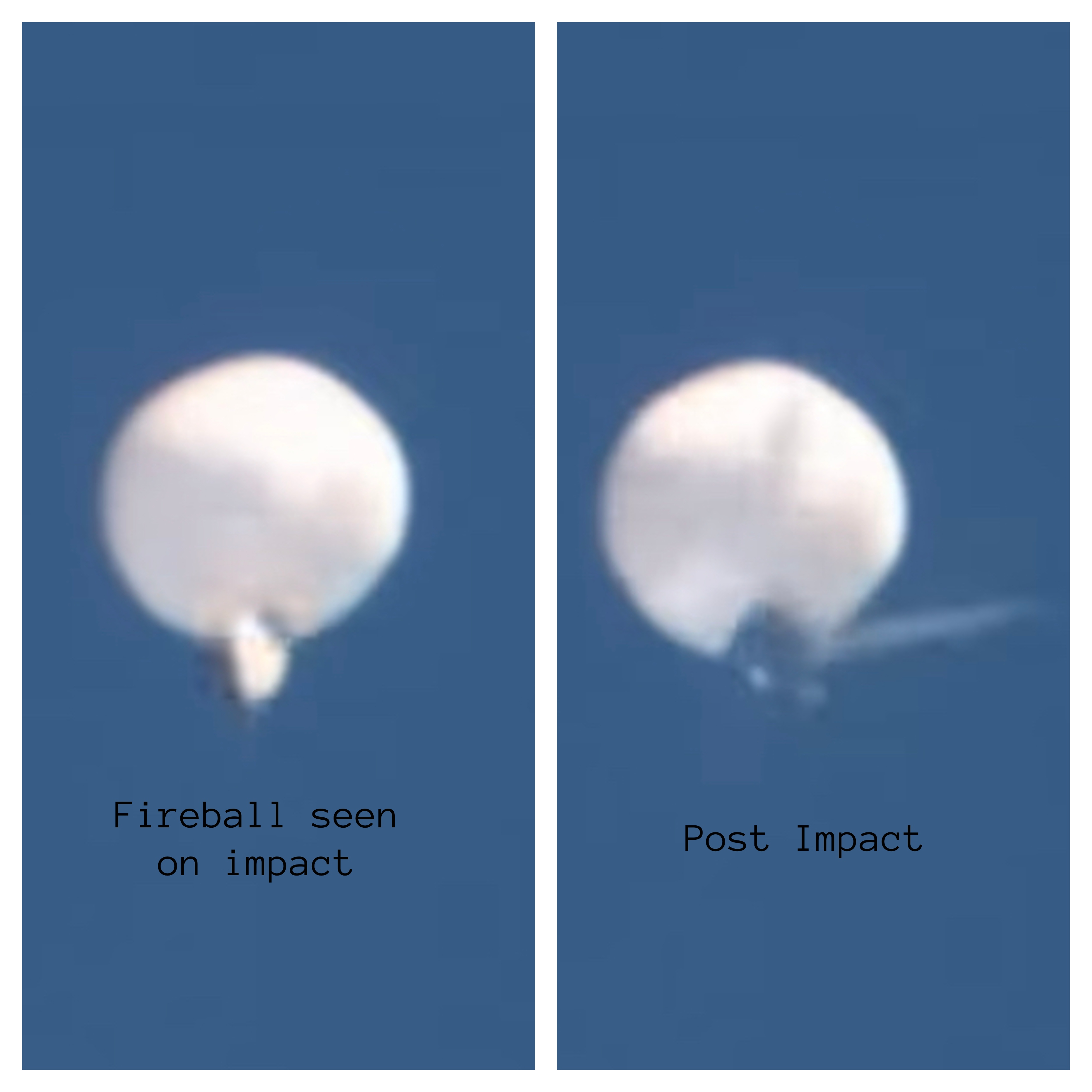

When it does, however, its landing location will be wildly unpredictable owing to the effects of wind and air. It will be traveling much slower than when it was first fired, as its terminal velocity (due to air resistance) is far lower than the initial muzzle speed. But even so, these falling bullets can injure or even kill people: something that’s traditionally been most likely on July 4th and New Year’s in the United States, but that’s increasingly becoming a hazard in early 2023 with the hullaballoo surrounding “spy balloons” flying over American airspace.

Here’s the science behind how “celebratory gunfire” — or any type of firearms fired up into the air — can, and often does, kill people.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize that bullets are dangerous. When a typical AK-47 fires, the bullet leaves the muzzle at about 1500 miles-per-hour (about 670 meters-per-second), which is approximately double the speed of sound. Even though the bullet itself weighs only 0.2 ounces (with a mass of around 5 grams), it possesses the energy of a brick dropped from a 16 story building. With all that energy concentrated into a very small area, it can easily break through your skin, causing severe internal damage and, if it pierces the right (or wrong) organs, even death.

Still, you might recognize that air resistance is going to play a substantial role in slowing that bullet down when it returns to Earth. A bullet that’s fired straight up would only hit you with that same speed when it came back down if you were on a world without an atmosphere, such as the Moon. On Earth, however, our substantial atmosphere generates a significant amount of air resistance, which changes the entire story.

A bullet fired straight up on Earth, assuming there’s no wind, might still be able to reach a maximum height of around three kilometers (about 10,000 feet), before reaching a vertical speed of zero and then falling back down to Earth. This might be high enough to shoot down the low-flying airplanes that flew during World War I — after all, that’s how the famed Red Baron was killed, by a gun fired from the ground — but with modern aircraft reaching ~9-10 kilometers (exceeding 30,000 feet) and balloons flying even higher in Earth’s stratosphere, guns are a wildly ineffective tool to bring them down.

However, just like a human skydiver only accelerates for a few seconds before reaching terminal velocity, the air resistance acting on the bullet will prevent it from reaching speeds even close to muzzle velocity ever again. Instead, a falling bullet comes back down with a speed of only around 150 miles-per-hour (241 kilometers per hour), which is just 10% of the speed it was fired with. Because of how energy works (proportional to your speed squared), a bullet that falls from high in the air only possesses 1% of the energy of a bullet newly fired from a gun: the equivalent of a brick dropped from a height of just 50 cm (about 20 inches) off the ground.

In terms of speed and energy, this simple treatment does, in fact, correctly give us the properties of a bullet fired up into the air when it hits the ground. But in terms of location, bullets that are fired even straight up can actually come back down up to two miles (about three kilometers) away from where they were fired.

A 150 mile-per-hour bullet won’t be lethal in most instances, but there are two factors that can change the equation dramatically.

- Bullets that are fired at an angle, rather than straight up, may never stop and begin tumbling; instead, they can maintain much greater speeds: many hundreds of miles-per-hour.

- If a bullet has enough speed to break the skin, it can potentially be lethal; this occurs at different speeds for different bullets and different individual people.

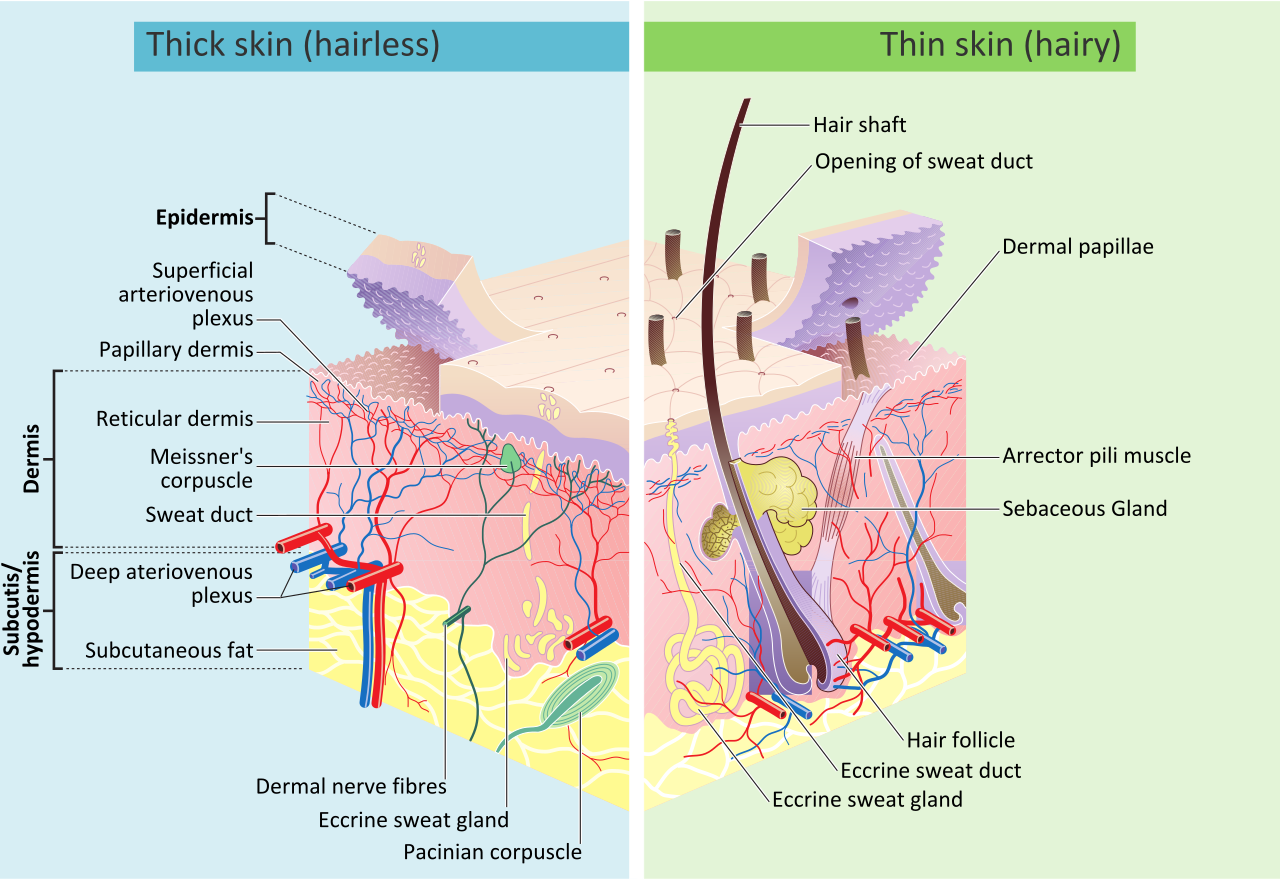

The type of bullet used is tremendously important for determining whether it’s possible for a bullet to break your skin or not, as well as the type of skin in question. In general, the accepted threshold for where a bullet will break the skin barrier is 136 miles-per-hour, but the true figure varies wildly. Some combinations of perfectly round bullets impacting thick skin will bounce off a human at speeds up to 225 miles-per-hour, but that’s the ideal case.

A pointier bullet can move slower and still break the skin, as will a smaller-caliber bullet, having its force concentrated over a much smaller area. For instance (according to Mattoo’s equation):

- buckshot will perforate skin at 145 miles-per-hour,

- bullets from a .38 caliber revolver break skin at 130 miles-per-hour,

- 9mm handgun bullets can break skin at just 102 miles-per-hour,

- and a .30 caliber bullet will break skin at only 85 miles-per-hour.

There are also enormous variations in how easy it is to puncture skin: both from person-to-person and across different places on an individual’s body. Healthy adults tend to have the most difficult skin to puncture, as it’s both thick and high in elasticity. Babies and young children have thinner skin, while the elderly have thicker but low-elasticity skin, making it easier to tear or puncture. Even just on your face, the skin on your upper lip is 50% thicker than the skin on your cheek, while the skin just below your cheekbones (close to your nose) is even thinner, particularly in the elderly.

A large suite of military ballistics tests were compiled in a report by U.S. Army Major General Julian Hatcher, which determined that a .30 caliber bullet reaches a terminal speed of 200 miles-per-hour: enough to break skin in practically all cases.

It sounds extremely dangerous, but you might think that such an occurrence of a stray bullet hitting a person is so rare that it wouldn’t matter. Perhaps, you’d reason, there are so few airborne bullets and so few people compared to the land area over which these bullets could land that deaths and injuries pretty much never occur.

Oh, how wrong you’d be. Just anecdotally:

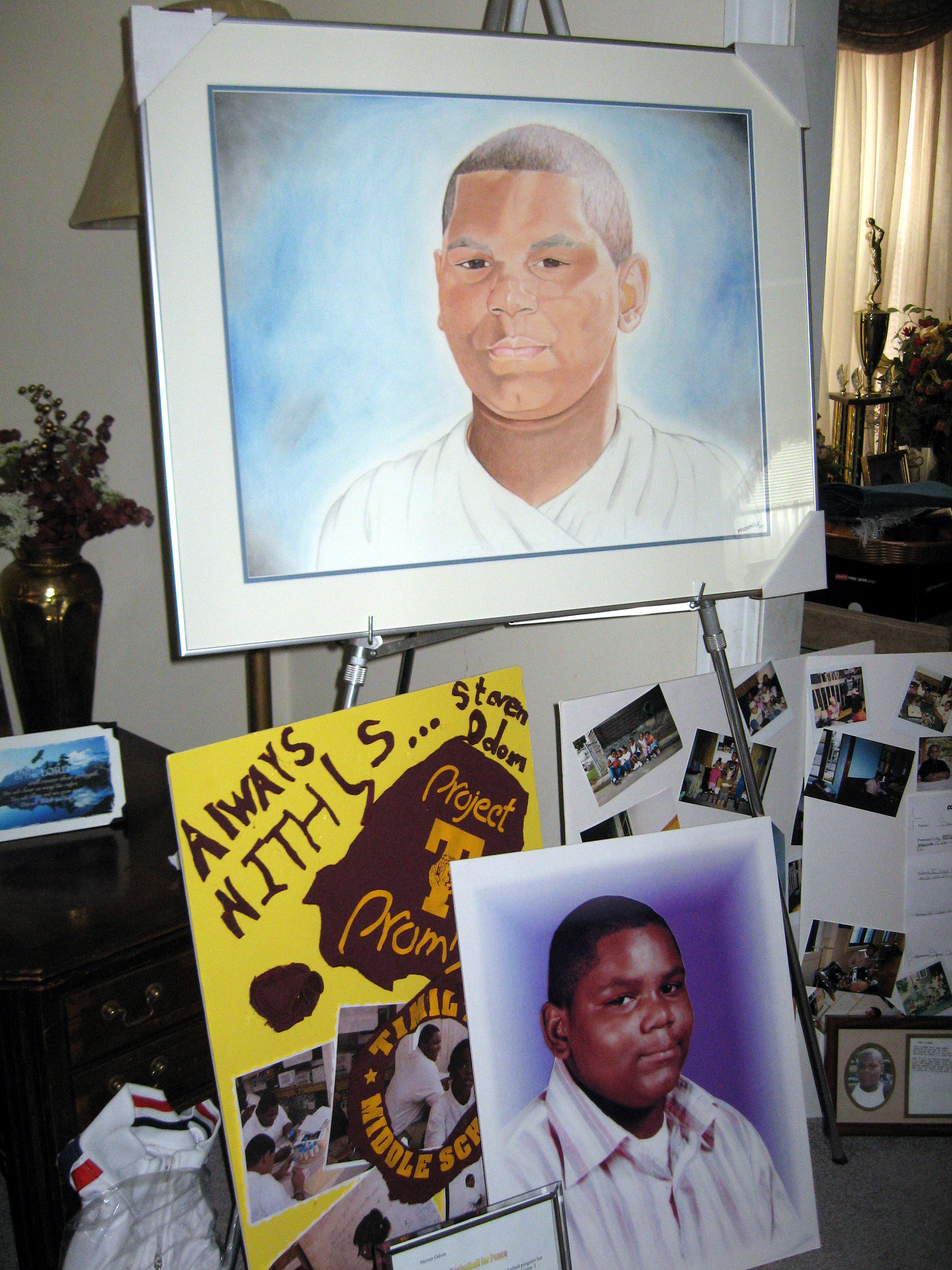

- In 2010, Marquel Peters, four years old, was killed by a stray falling bullet in Decatur, GA.

- In 2013, Aaliyah Boyer, age 10, was killed on New Year’s by a falling bullet in Maryland.

- In 2017, Javier Suarez Rivera, age 43, was killed moments after midnight after stepping outside his residence on New Year’s in Houston, TX.

- Also on New Year’s in 2017, Texas State Representative Armando Martinez was hit in the head with a stray bullet; he survived.

- On July 1st, 2017, Noah Inman, age 13, was struck and later died from a stray bullet in Indiana, likely from celebratory gunfire.

- And in 2019, Dr. Chad Wilson’s emergency room removed a stray copper bullet from the top of a woman’s head due to celebratory gunfire.

According to a 1-year study conducted on stray bullets, 4.6% of all deaths and injuries occur as a direct result of celebratory gunfire.

Most of us shouldn’t need coaxing to avoid firing a gun up into the air; in fact, celebratory gunfire is illegal in all 50 states across the country. Moreover, if someone is killed by a bullet that you fired, in many states you can be charged with a felony. This leads many to ask the obvious question, “If celebratory gunfire is illegal, then why are guns fired into the air at military funerals and events? Why do we have ’21 gun salutes’ if this is so dangerous?”

The answer is simple: those events use blanks, not real bullets.

Unfortunately, most celebratory gunfire that occurs in communities — and practically every attempt to shoot at a perceived threat like a spy balloon or a UFO — uses live ammunition, which is what results in these potentially lethal consequences. A bullet fired up into the air doesn’t cease to be dangerous because it’s out of sight; typically between 20 and 90 seconds later (but up to two full minutes later), it will eventually come down.

The most dangerous conditions for celebratory gunfire occur in urban areas with a high population density, particularly when large crowds are outside late at night. It should be no surprise that the night of July 4th and New Year’s Eve are typically the peaks of stray bullet injuries from this cause. Dense, small bullets will achieve higher terminal velocities than lighter, larger bullets, making them more dangerous. At high altitudes, there’s less air resistance, meaning that stray bullets will carry more kinetic energy and pose a higher risk of death than at low altitudes.

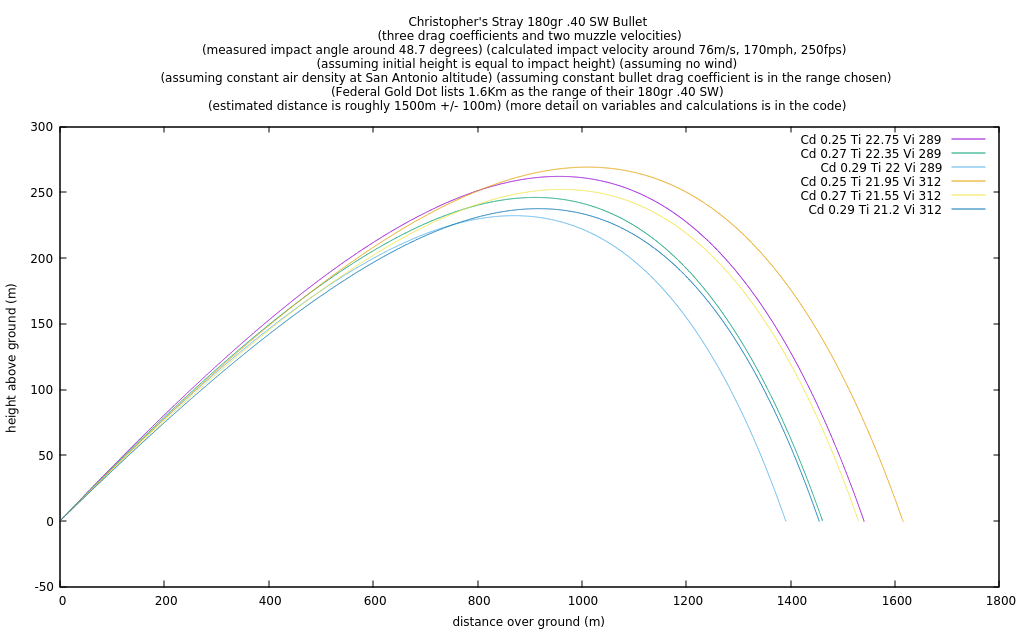

The behavior that is riskiest to others, though, is firing a bullet at an angle into the air, rather than straight up. Bullets that are fired very close to perfectly vertical will lose the most speed; those that are at an angle can maintain velocities that ensure they will puncture skin, regardless of where or whom they hit. This is particularly relevant when it comes to civilians seeing balloons or other unidentified aerial phenomena, as they’re typically spotted at some angle relative to the viewer, not directly overhead at the zenith.

Although celebratory gunfire continues to be an unnecessary cause of injury and death in the United States and across the world, there are a number of positive aspects to focus on. A CDC report in 2004 noted that celebratory gunfire in Puerto Rico killed 2 and injured 25 on an annual basis; since 2012, campaigns to reduce that number have successfully eliminated New Year’s deaths from stray bullets in Puerto Rico. This provides direct evidence of a strategy that’s simple but effective: raising awareness works.

Firing a gun into the air creates a potential hazard for anyone within a two mile radius of the person firing the gun, and the danger will not subside until a full two minutes have passed since the final gunshot. Although there are no recorded incidents of the person firing the gun also getting hit by their own stray bullet, it remains a frightening possibility, but that’s not the reason it’s against the law. As is often the case, your individual freedom to celebrate ends when it infringes on the lives and safety of innocent bystanders. If you happen to be near a populated area when a balloon appears in the skies, spread the word about the dangers of gunfire, and most importantly, don’t shoot!