Science discovers how complex life came to the Galapagos Islands

From inhospitable volcanoes to life so unique we discovered evolution there, the Galapagos is an incredible scientific story.

“I was always amused when overtaking one of these great monsters [a tortoise], as it was quietly pacing along, to see how suddenly, the instant I passed, it would draw in its head and legs, and uttering a deep hiss fall to the ground with a heavy sound, as if struck dead. I frequently got on their backs, and then giving a few raps on the hinder parts of their shells, they would rise up and walk away; — but I found it very difficult to keep my balance.”

–Charles Darwin

One glance at the Galapagos Islands, and you’re sure to have your breath taken away. Giant tortoises, flightless birds, marine iguanas, and dandelions the size of trees are among the many incredible living beings you’ll find, unique to this string of islands. The fact that seeds were blown here by the wind, that eggs and creatures either flew, swam, or drifted here, and that ocean life followed the currents to the waters of the Galapagos is the easy part to envision. What’s difficult is to picture how these volcanic islands came to be hospitable to such a diversity of creatures. Thanks to some simple physics, however, we finally think we understand.

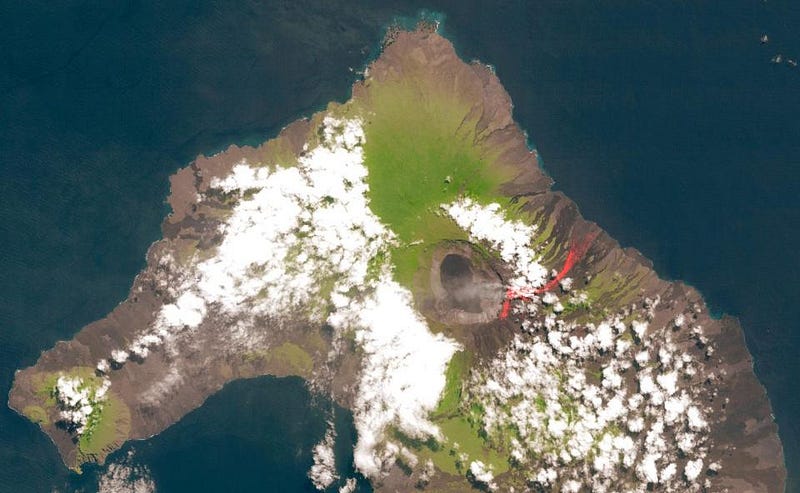

The Galapagos islands form at the bottom of the ocean, where weak spots in the Earth’s crust allow magma to erupt upwards, forming columns, plumes and cones of rock. Eventually, over a few hundred thousand years, some of these undersea islands erupt above the ocean’s surface, continuing to grow for as long as the lava continues to rise up to the top of the still-forming islands. Only when the sea floor spreads enough so that the upwelling molten rock is directed elsewhere — and so that resurfacing and lava flows on any particular island become a thing of the past — is the island ready to house what will become its permanently situated flora and fauna.

But at the beginning, only the life accustomed to living on the volcanic rock near the ocean shores can succeed. Mosses, algae, semi-aquatic plants and the animals that feed on them will thrive near the coast, but elsewhere on the island is much more foreboding. Volcanic rock is largely inhospitable to complex life, as the dry, nutrient-free rock cannot sustain very much at all. But there’s a simple solution that nature provides to this hellish landscape: rain.

Rain is a rarity over this part of the ocean, but the newest, highest-peaked Galapagos islands use physics to create their own rainclouds. As wind sweeps across the ocean surface, a certain amount of moisture makes it into the air just above sea level. When that air encounters a towering island, some portion of the air rises up and over it, where the change in altitude causes it to cool. The warm, moist, equatorial air rises high enough and cools sufficiently so that the water vapor gets pulled out into the liquid phase, forming clouds. When the clouds become heavy enough with water, rain falls onto the island, which happens on practically a daily basis for the highest, newest islands.

Continued, thorough rains can erode the rock, while deposits of bacteria, fungal spores, plant seeds and more can take hold, spreading throughout the island. Over thousands of years, this enables the creation of fertile soil, capable of housing large plants such as ferns, bushes and trees, as well as fungal colonies that decompose them and animals that devour them. The Galapagos Islands are short-enough lived and isolated enough — each one lasts only for around four million years before eroding away below the surface — that there are no large land predators there. Other than the recent arrival of humans, there likely never have been.

As a result, the large animals present there exhibit a phenomenon known as “island tameness,” where they are unafraid and do not flee from the approach of other, unfamiliar animals. In a world where your ancestors, going back hundreds of generations or more, have never known a predator more advanced than a crab, you have no reason to maintain your defensive behaviors, and can instead focus on gathering food, mating, and enjoying a literal paradise.

Incredibly, all it took was volcanism, wind passing over the ocean, and the natural process of rain to bring a habitable environment to the middle of the ocean. The arrival of not only single-celled life but also complex plants, animals and fungi was not merely serendipitous, but inevitable, given how powerful winds and ocean currents are.

From a cursory outside view, the Galapagos may seem like a complete oddity: teeming with a diversity of megafauna and megaflora unique to each island. But physics puts the right ingredients in place — fertile land with winds, ocean access, and, via rain, a ready supply of fresh water — and biology takes care of the rest!

Starts With A Bang is based at Forbes, republished on Medium thanks to our Patreon supporters. Order Ethan’s first book, Beyond The Galaxy, and pre-order his next, Treknology: The Science of Star Trek from Tricorders to Warp Drive!