Are parallel Universes physically real, or just an unsupported idea?

- Sparked by inventive fiction involving the multiverse, the idea of an infinite series of parallel Universes offers us hope that, somewhere, there’s a version of us that’s living our ideal life.

- But could these parallel Universes be physically real? There are two ways to think about it that are physically well-motivated: in the contexts of inflationary cosmology and quantum physics.

- But do either of these physically rooted options offer the ultimate possibility: alternate-reality versions of you that simply made different decisions, leading to vastly different outcomes for your life?

You’ve likely imagined it before: another Universe out there, just like this one, where all the random events and chances that brought about our reality exactly as it is played out just the same. In every way, every quantum event that had a set of possibilities as to which outcomes could have occurred, have played out identically in that other Universe to the one we inhabit today. Except, that is, until right now, when you made one fateful decision in this Universe, you took an alternate path in that other Universe. These two Universes, which ran parallel to one another for so long, suddenly diverged.

Perhaps our Universe, with the version of events we’re familiar with, isn’t the only one out there. Perhaps there are other Universes, perhaps even with different versions of ourselves, different histories and alternate outcomes from what we’ve experienced. This isn’t merely fiction — although it plays an incredible role in a variety of fictional settings — but one of the most exciting possibilities brought about through theoretical physics. Here’s what the science says about whether parallel Universes might actually be real.

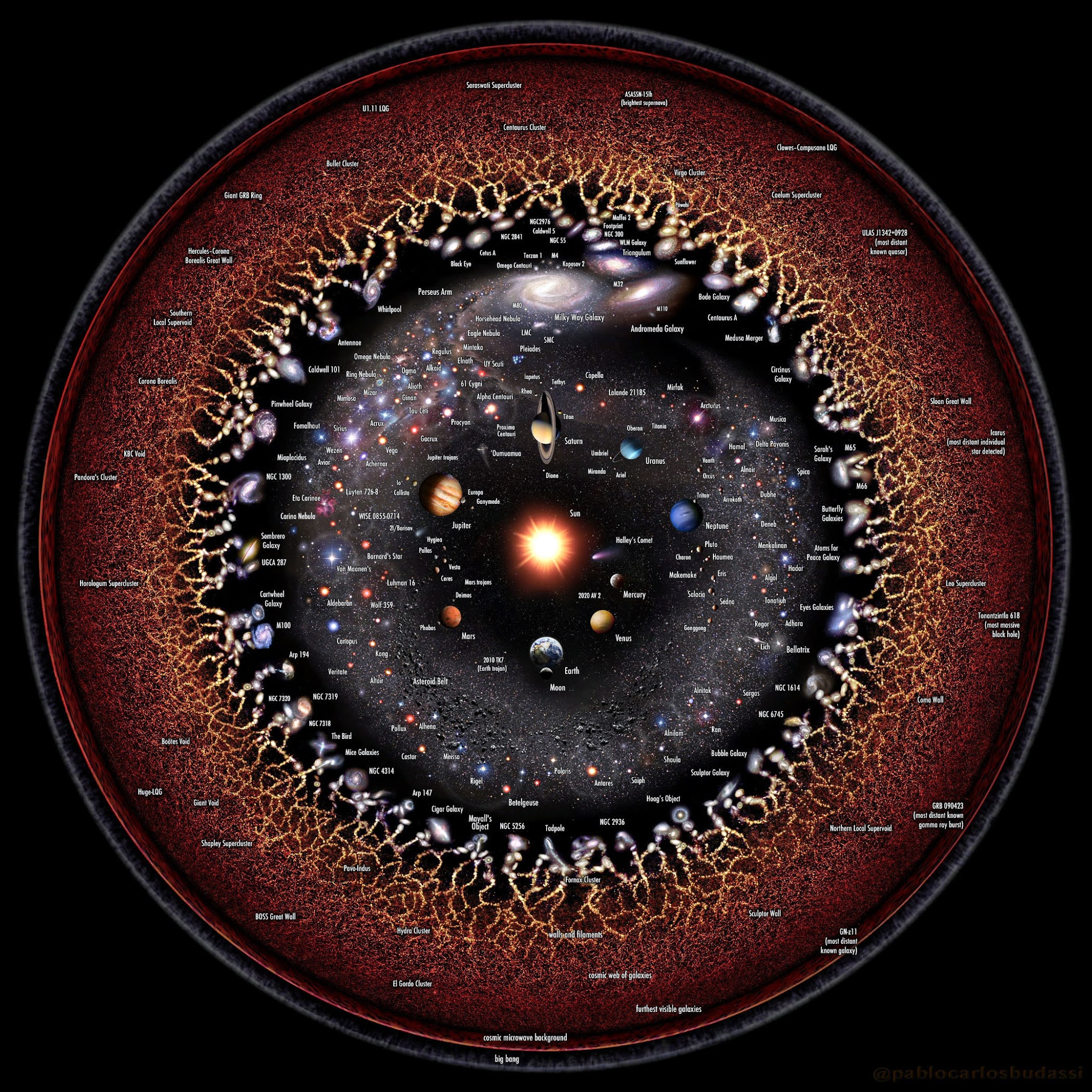

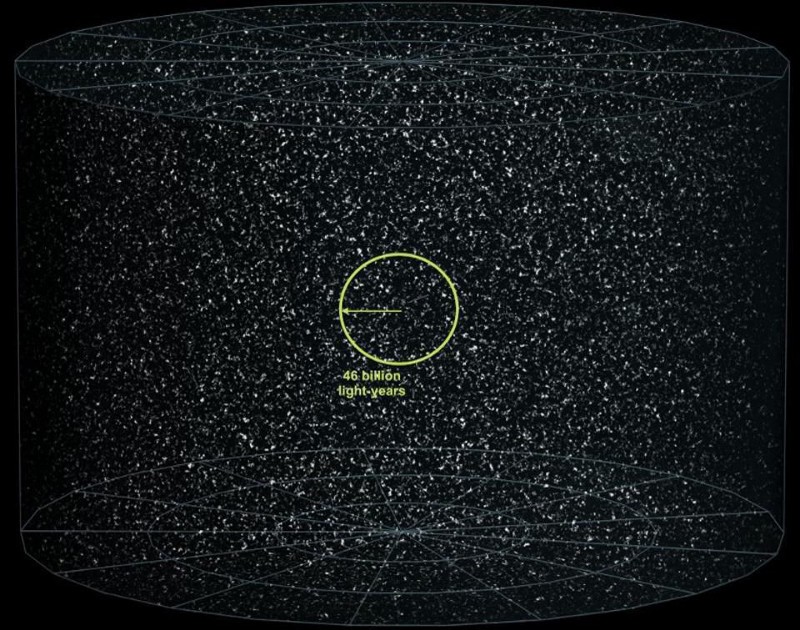

As vast as our Universe might be, the part that we can see, access, affect, or be affected by is finite and quantifiable. Including photons and neutrinos, it contains some 1090 particles, clumped and clustered together into approximately 6-to-20 trillion galaxies, with perhaps another 9-to-30 trillion galaxies that will reveal themselves to us as the Universe continues to expand.

Each such galaxy comes with around a trillion stars inside it (on average), and these galaxies clump together in an enormous, cosmos-spanning web that extends for 46 billion light-years away from us in all directions. But, despite what our intuition might tell us, that doesn’t mean we’re at the center of a finite Universe. In fact, the full suite of evidence indicates something quite to the contrary.

The reason the Universe appears finite in size to us — the reason we can’t see anything that’s more than a specific distance away — isn’t because the Universe is actually finite in size, but is rather because the Universe has only existed in its present state for a finite amount of time.

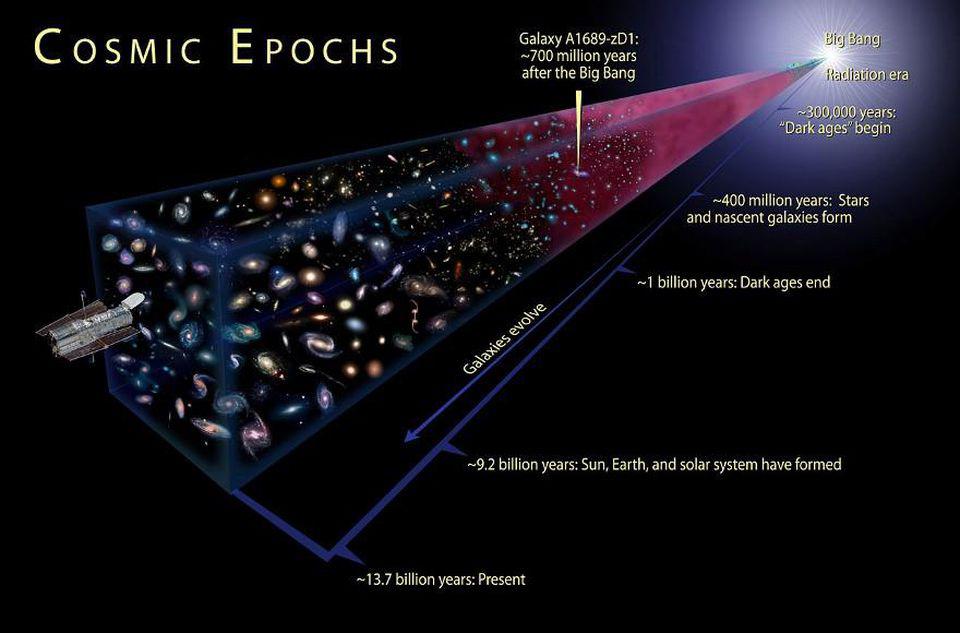

If you learn nothing else about the Big Bang, it should be this: the Universe was not constant in space or in time, but rather has evolved from a more uniform, hotter, denser state to a clumpier, cooler, and more diffuse state today. As we go to earlier and earlier times, the Universe appears smoother and with fewer, less-evolved galaxies; as we look to later times, the galaxies are larger and more massive, consisting of older stars, with greater distances separating galaxies, groups, and clusters from one another.

This has given us a rich Universe, containing many relics from our shared cosmic history, including:

- many generations of stars,

- an ultra-cold background of leftover radiation,

- galaxies that appear to recede away from us ever-more-rapidly the more distant they are,

- with a fundamental limit to how far back we can see.

The limit to our cosmic perspective is set by the distance that light has had the ability to travel since the moment of the Big Bang.

But this in no way means that there isn’t more Universe out there beyond the portion that’s accessible to us. In fact, there’s both observational and theoretical arguments that point to the existence of much more Universe beyond what we see: perhaps even infinitely more.

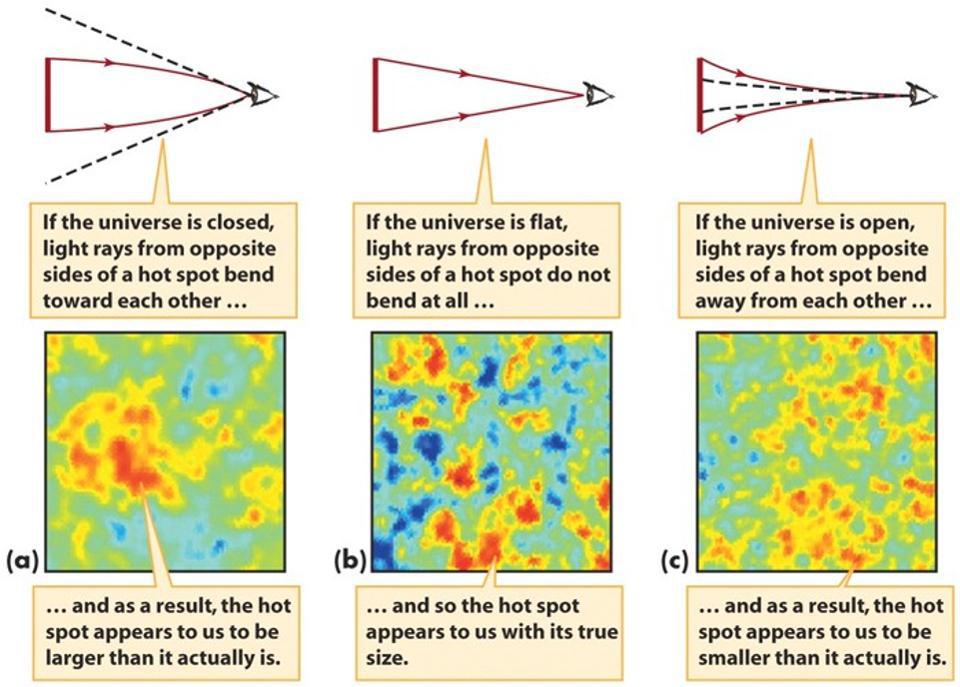

A finite Universe would display a number of telltale signals that enable us to determine that we don’t live in an infinite sea of spacetime. We’d measure our spatial curvature, and could find that the Universe was shaped like a sphere in some way, where if you traveled in a straight line for long enough, you’d return to your starting point. You could look for repeating patterns in the sky, where the same object appeared in different locations simultaneously. You could measure the Universe’s smoothness in temperature and density, and see how those imperfections evolved over time.

If the Universe were finite, we would see a specific set of properties inherent to the patterns that the Big Bang’s leftover temperature fluctuations displayed. But what we see instead are a different set of patterns, teaching us the exact opposite: the Universe is indistinguishable from being perfectly flat and infinitely large.

Of course, we can’t know that for certain. If all you had access to was your own backyard, you couldn’t measure the curvature of the Earth, because the portion you had access to was indistinguishable from flat. Based on the portion of the Universe we see, we can state that if the Universe is finite and does curve back on itself, it must have at least millions of times the volume of the portion we can see, with no upper limit to that figure. But theoretically, the implications of our observations paint a picture that’s even more tantalizing.

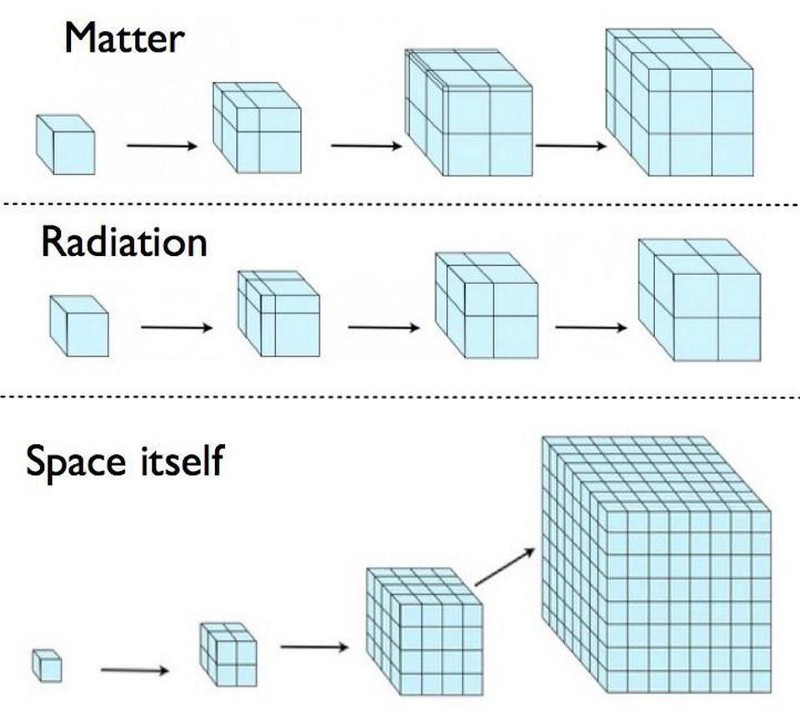

You see, we can extrapolate the Big Bang backward to an arbitrarily hot, dense, expanding state, and find that it couldn’t have gotten infinitely hot and dense early on. Rather, above some energy and before some very early time, there was a phase that preceded the Big Bang, set it up, and led to the creation of our observable Universe. That phase, a period of cosmological inflation, describes a phase of the Universe where rather than being full of matter and radiation, the Universe was filled with energy inherent to space itself: a state that causes the Universe to expand at an exponential rate.

In a Universe filled with matter or radiation, the expansion rate will decrease over time, as the Universe becomes less dense. But if the energy in inherent to space itself, the density will not drop, but rather remains constant, even as the Universe expands. In a matter or radiation dominated Universe, the expansion rate slows as time goes on, and distant points recede from one another at ever slower speeds. But with exponential expansion, the rate doesn’t drop at all, and distant locations — as time goes on incrementally — get twice as far away, then four times, eight, sixteen, thirty-two, etc.

Because the expansion is not just exponential but also incredibly rapid, “doubling” happens on timescale of around 10-35 seconds. This implies:

- by the time 10-34 seconds have passed, the Universe is around 103 (or 1000) times its initial size,

- by the time 10-33 seconds have passed, the Universe is around 1030 (or 100010) times its initial size,

- by the time 10-32 seconds have passed, the Universe is around 10300 (or 1000100) times its initial size,

and so on. Exponential isn’t so powerful because it’s fast; it’s powerful because it’s relentless.

Now, obviously the Universe didn’t continue to expand in this fashion forever, because we’re here. Inflation occurred for some amount of time in the past, but then ended, setting up the Big Bang.

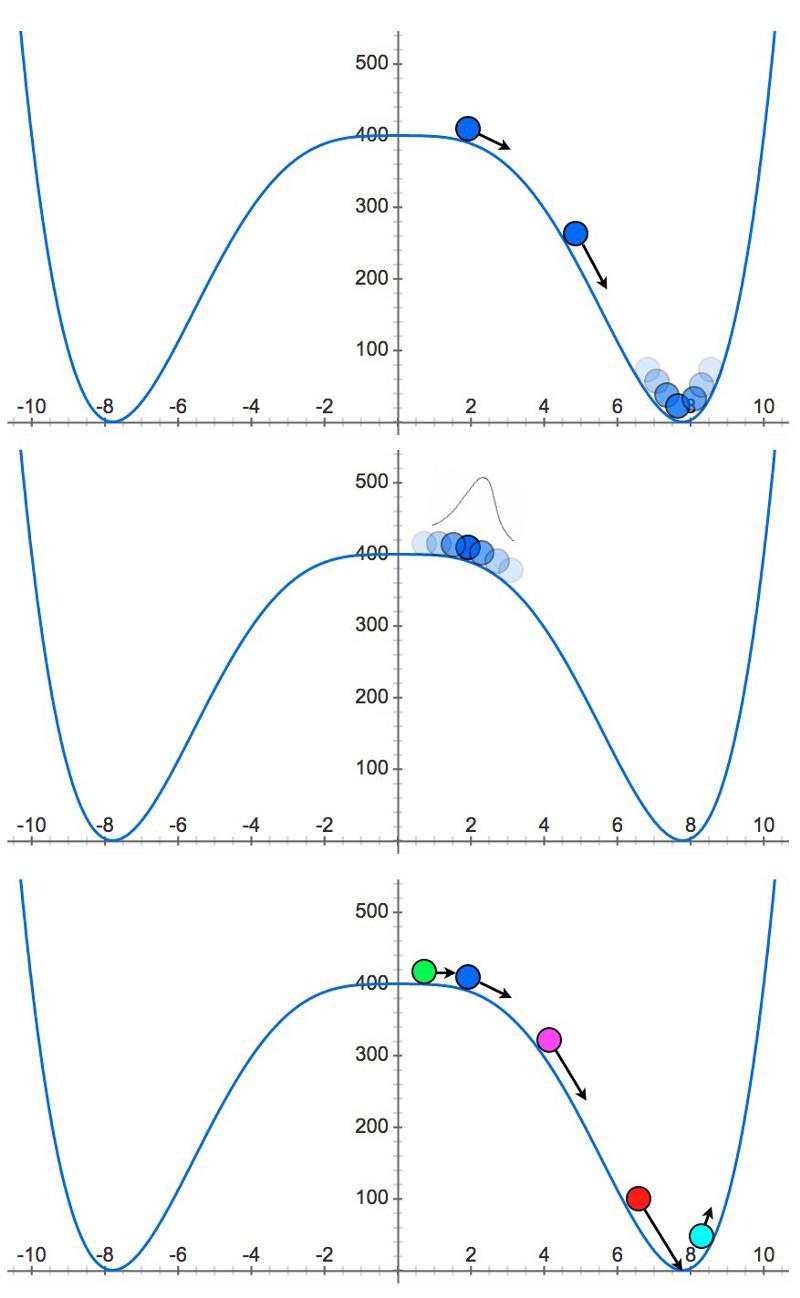

One useful way to think about inflation is like a ball rolling very slowly down from the top of a very flat hill, as shown in the top panel, above. As long as the ball remains near the topmost plateau, it rolls slowly and inflation continues, causing the Universe to expand exponentially. Once the ball reaches the edge and rolls down into the valley, however, inflation ends. As it oscillates back-and-forth in the valley, that rolling behavior causes the energy from inflation to dissipate, converting it into matter-and-radiation, ending the inflationary state and beginning the hot Big Bang.

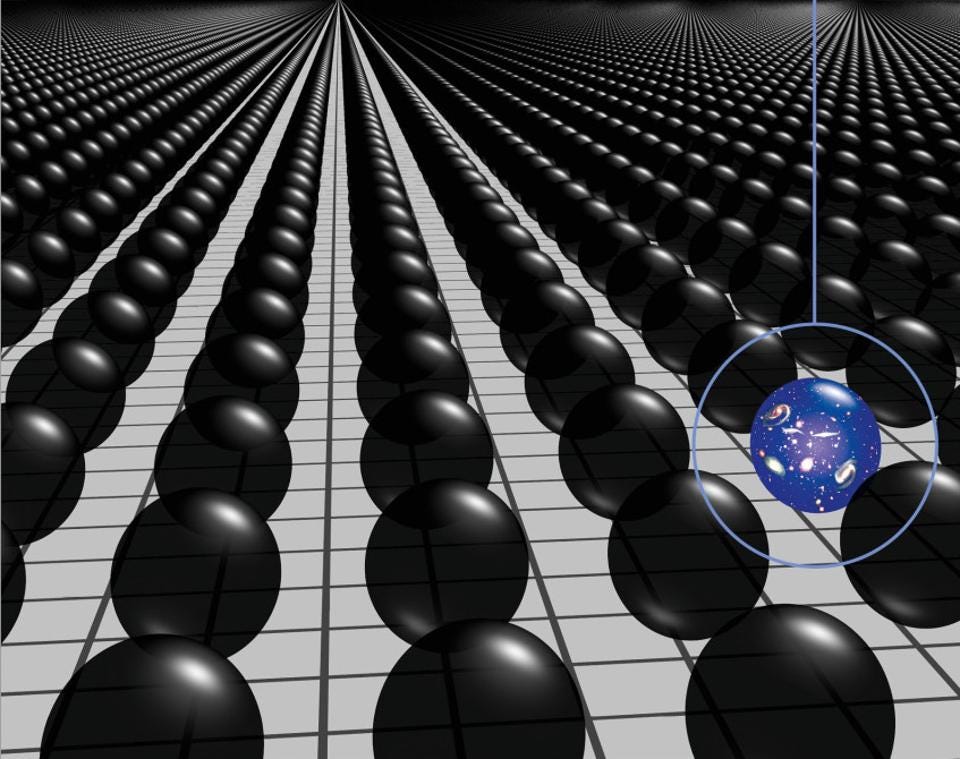

But inflation doesn’t occur everywhere at once and end everywhere at once. Everything in our Universe is subject to the bizarre quantum laws of reality, even inflation itself. When we consider that fact of nature, as shown in the middle and bottom panels in the above image, an inevitable line of thought emerges.

- Inflation isn’t like a ball — which is a classical field — but is rather like a wave that spreads out over time, like a quantum field.

- As time goes on and more-and-more space gets created due to inflation, certain regions, probabilistically, are going to be more likely to see inflation come to an end, while others will be more likely to see inflation continue.

- The regions where inflation ends will give rise to a Big Bang and a Universe like ours, while the regions where it doesn’t will continue to inflate for longer.

- As time goes on, because of the dynamics of expansion, no two regions where inflation ends will ever interact or collide; the regions where inflation doesn’t end will expand between them, pushing these “bubble Universes” apart from one another.

There are, of course, a great many unknowns associated with this inflationary state.

We don’t know how long inflation lasted before it ended and gave rise to the Big Bang, and whether that duration was short, long, or infinite.

We don’t know if the regions where inflation ended are all the same as one another, with the same laws of nature, fundamental constants, and quantum properties and fluctuations as our own Universe.

And we don’t know whether these various Universes are connected in some physically meaningful way, or whether they play by their own individual rules and don’t affect one another.

The dream of parallel Universes, after all, is that the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics might have a place for all of those alternate realities — where different decisions were made and different outcomes were achieved — to truly reside.

Is it possible that there’s a Universe out there where everything happened exactly as it did in this one, except you did one tiny thing different, and hence had your life turn out incredibly different as a result?

- Where you chose the job overseas instead of the one that kept you in your country?

- Where you stood up to the bully instead of letting yourself be taken advantage of?

- Where you kissed the one-who-got-away at the end of the night, instead of letting them go?

- And where the life-or-death event that you or your loved one faced at some point in the past had a different outcome?

Maybe. It’s certainly wishful thinking to believe so. But for that to actually be our physical reality, those unknowns about our Universe need to have specific answers that may not be very likely.

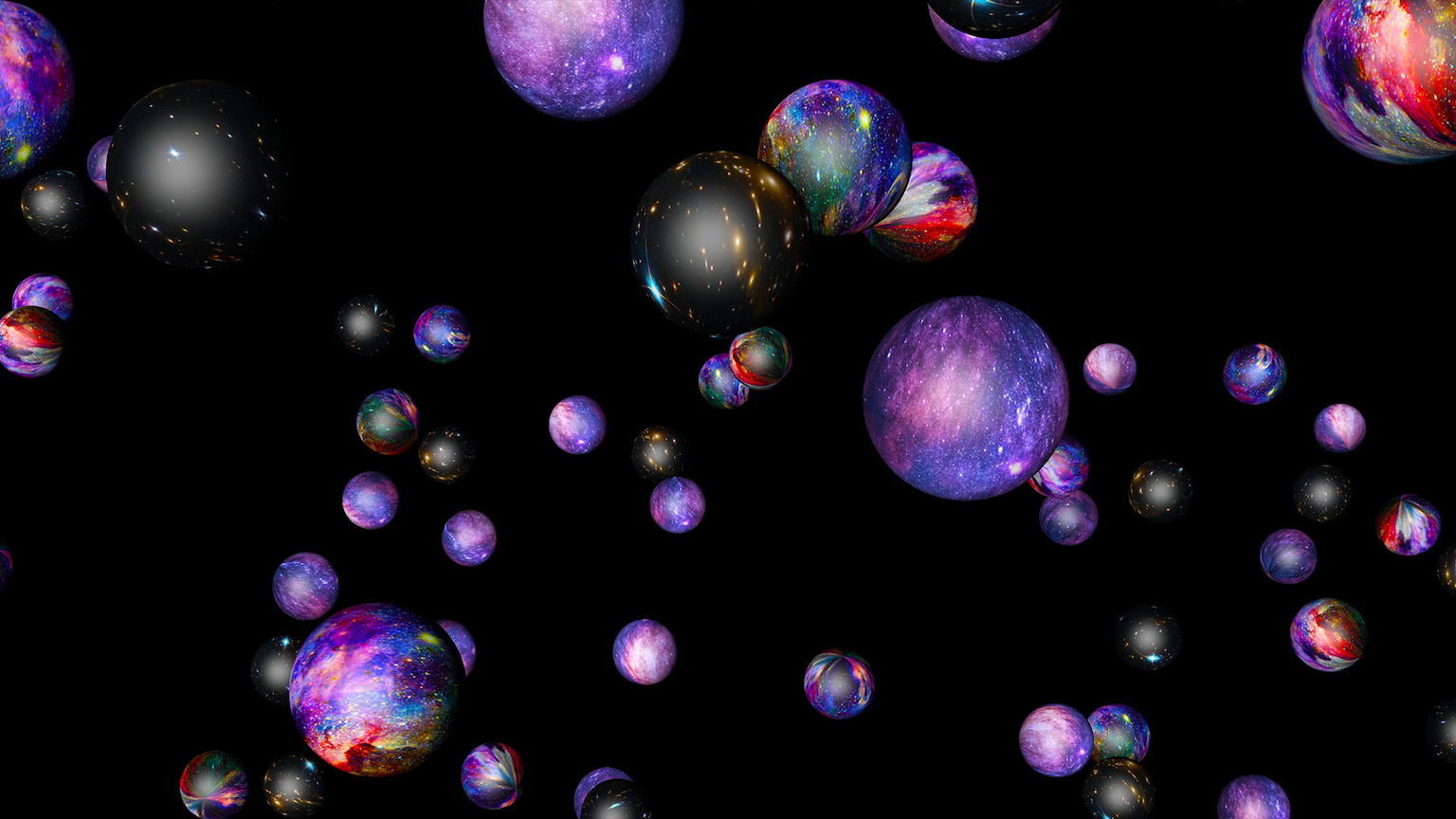

First off, the inflationary state that preceded the Big Bang must have lasted for not just a long time, but a truly infinite amount of time. Let’s assume that the Universe inflated — i.e., expanded exponentially — for 13.8 billion years. That would create enough volume of space for 10^(1050) Universes just like our own, or 10100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 Universes. That is, no doubt, truly a gargantuan number. But it’s still a finite number, and if it’s not bigger than the number of possible outcomes, it isn’t big enough to contain the possibilities that the notion of parallel Universes would necessitate.

So let’s think about quantifying the number of possible outcomes. There are ~1090 particles in our Universe, including photons and neutrinos, and we require that every one of them have the same history of interactions since the Big Bang that they experienced here to duplicate our Universe. We can quantify the odds by taking 1090 particles and giving them 13.8 billion years to interact. We then have to ask how many possible outcomes there are given the laws of quantum physics and the rate of particle interactions.

As large as a double exponential is — as 10^(1050) is — it’s far smaller than our estimate for the number of possible quantum outcomes for 1090 particles, which is somewhat larger (1090)! That ! stands for factorial, where 5! is 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 *1 = 120, but 1000! is 1000 * 999 * 998 * … * 3 * 2 * 1 and is a 2477-digit number. Part of the reason the number of possibilities rises so quickly is because many quantum processes don’t simply have a discrete set of possible outcomes, but a continuous one. If you tried to calculate (1090)!, you’d find that it’s many googolplexes larger than a relatively mundane number like 10^(1050).

It’s true: both numbers go to infinity. The number of possible parallel Universes tends to infinity, but does so at a particular (exponential) rate, but the number of possible quantum outcomes for a Universe like ours also tends to infinity, and does so much more quickly. As both mathematicians and John Green fans know, some infinities are bigger than others.

What this means is that, unless inflation has been occurring for a truly infinite amount of time, there are no parallel Universes out there identical to this one. The number of possible outcomes from particles interacting with each other increases faster than even the number of possible Universes arising from inflation; even an inflating multiverse isn’t large enough to hold the parallel Universes you’d need for the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics to put all of its alternate timelines.

Although we cannot prove whether inflation went on for an infinite duration or not, there is a theorem that demonstrates that inflationary spacetimes cannot be extrapolated back for arbitrary amounts of time; they have no beginning if so, and are called past-timelike-incomplete. Inflation may give us an enormously huge number of Universes that reside within a greater multiverse, but there simply aren’t enough of them to create an alternate, parallel you. The number of possible outcomes simply increases too fast for even an inflationary Universe to contain them all.

In all the multiverse, there is likely only one you. You must make this Universe count, as there is no alternate version of you. Take the dream job. Stand up for yourself. Navigate through the difficulties with no regrets, and go all-out every day of your life. There is no other Universe where this version of you exists, and no future awaiting you other than the one you live into reality. Make it count.