NASA’s Next Flagship Mission May Be A Crushing Disappointment For Astrophysics

If we don’t invest in learning about the Universe, we aren’t going to learn very much.

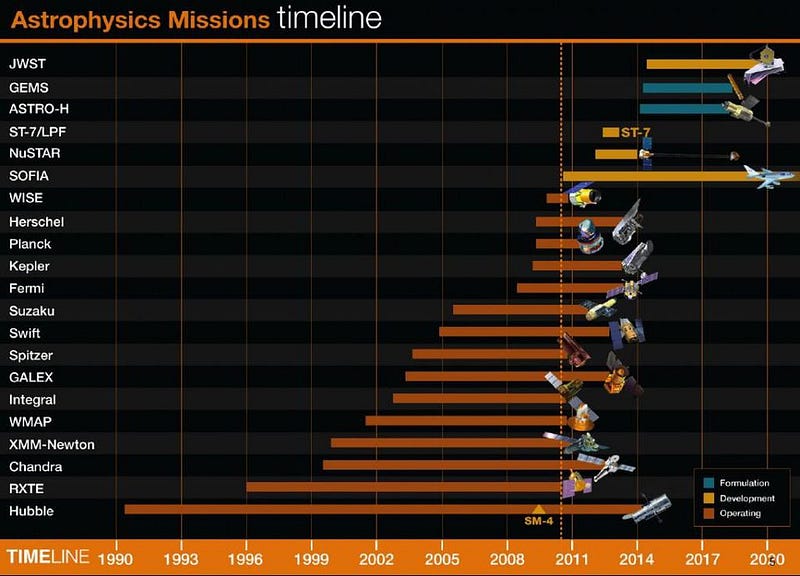

Every ten years, the field of astronomy and astrophysics undergoes a Decadal Survey. This charts out the path that NASA’s astrophysics division will follow for the next decade, including what types of questions they’ll investigate, which missions will be funded, and what won’t be chosen. The greatest scientific advances of all come when we invest a large amount of resources in a single, ultra-powerful, multi-purpose observatory, such as the Hubble Space Telescope. These are high-risk, high-reward propositions. If the mission succeeds, we can learn an unprecedented amount about the Universe as never before.

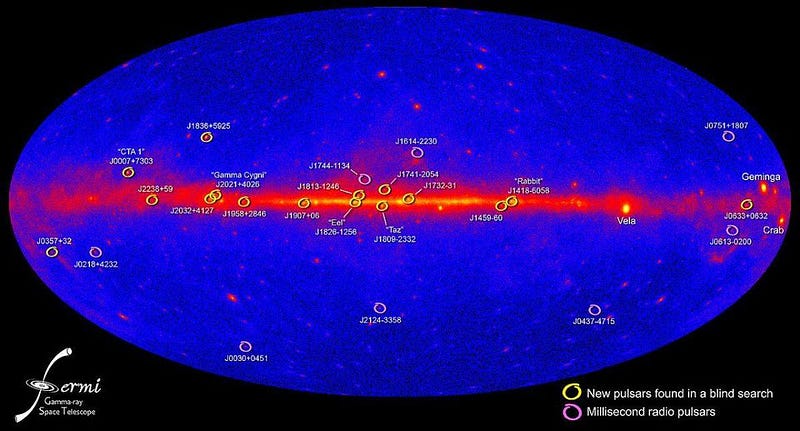

Even though the mission proposals go through NASA, its the National Research Council and the National Academy of Sciences that ultimately make the recommendations. Since the inception of NASA in the 1960s, these Decadal Surveys have shaped the field of astronomy and astrophysics research. They brought us our greatest ground-based and space-based observatories. On the ground, radio arrays like the Very Large Array and the Very Long Baseline Array, as well as the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, owe their origins to the decadal surveys. Space-based missions include NASA’s great observatories: the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray observatory, the Spitzer Space Telescope, and the Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory in the 1990s and early 2000s. Many of the missions flying today can trace their origins back to a prior Decadal Survey.

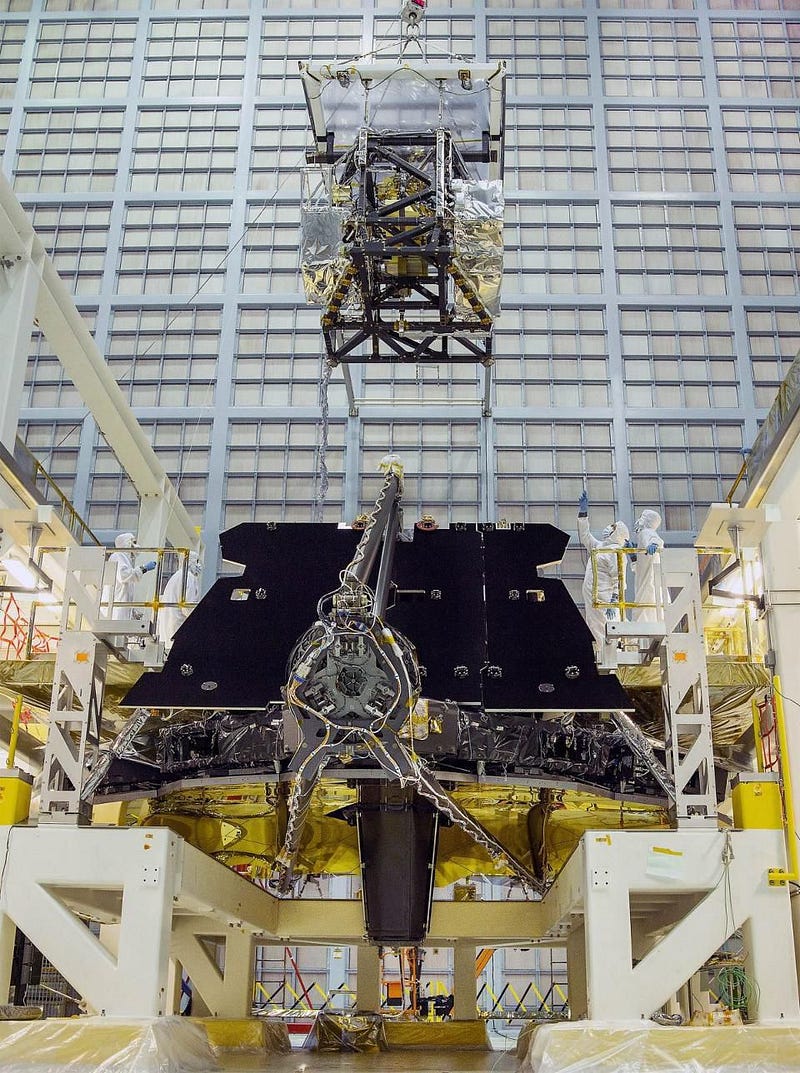

More recent Decadal Surveys, conducted this millennium, will bring us the James Webb Space Telescope, the WFIRST observatory designed to probe dark energy and exoplanets, and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), among others. They’ve identified the major, most important science goals of astronomy and astrophysics, including dark energy, exoplanets, supernovae, mergers of extreme objects, and the formation of the first stars and the large-scale structure of the Universe. But there was a warning issued in 2001’s report that hasn’t been heeded, and now it’s creating an enormous problem.

While a robust astronomy program has many benefits for the nation and the world, it’s vital to have a diverse portfolio of missions and observatories. Prior Decadal Surveys have simultaneously stressed the importance of the large flagship missions that drive the field forward like no other type of mission can, while warning against investing too much in these flagships at the expense of other small and medium-sized missions.

They’ve also stressed the importance of providing additional funding or securing external funding to support ongoing missions, facilities, and observatories. Without it, the development of new missions is hamstrung by the need to continually fund the existing ones.

Many austerity proponents and budget-hawks — both in politics and among the general public — will often point to the large cost of these flagship missions, which can balloon if unexpected problems arise. The far greater problem, however, would arise if one of these flagship missions failed.

When Hubble launched with its flawed mirror, unable to properly focus the light it gathered, fixing it became mandatory. Yes, it was expensive, but the far greater cost — to science, to society, and to humanity — would have been not to fix it. Our choice to invest in repairing (and upgrading) Hubble directly led to some of our greatest discoveries of all-time.

James Webb, similarly, is now over budget, and will require additional funds to complete. But the small, additional cost to get it right enormously outweighs the cost we’d all bear if we cheated ourselves and didn’t finish this incredible investment.

Now, the 2020 Decadal Survey approaches. The future course of astronomy and astrophysics will be charted, and one flagship mission will be selected as the top priority for a premiere mission of the 2030s. (James Webb was that mission for the 2010s; WFIRST will be it for the 2020s.) Unfortunately, a memorandum was just released by the astronomy & astrophysics director, Paul Hertz, of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. In it, each of the four finalist teams were instructed to develop a second architechture: a lower-cost, scientifically-inferior option.

It flies in the face of what a flagship mission actually is. Speaking at this year’s big American Astronomical Society meeting, NASA Associate Administrator Thomas Zurbuchen said,

What we learn from these flagship missions is why we study the Universe. This is civilization-scale science… If we don’t do this, we aren’t NASA.

And yet, these scaled-down architectures are by definition not as ambitious. It’s an indication from NASA that, unless the budget is increased to accommodate the actual costs of doing civilization-scale science, we won’t be doing it. Each of the four finalists has been instructed to propose an option with a total cost of below $5 billion, which will severely curtail the capabilities of such an observatory.

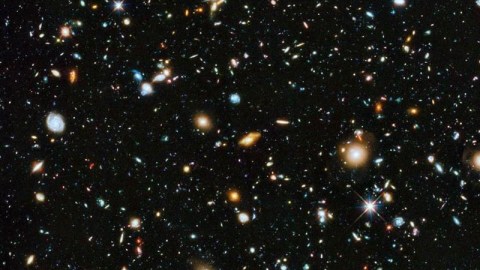

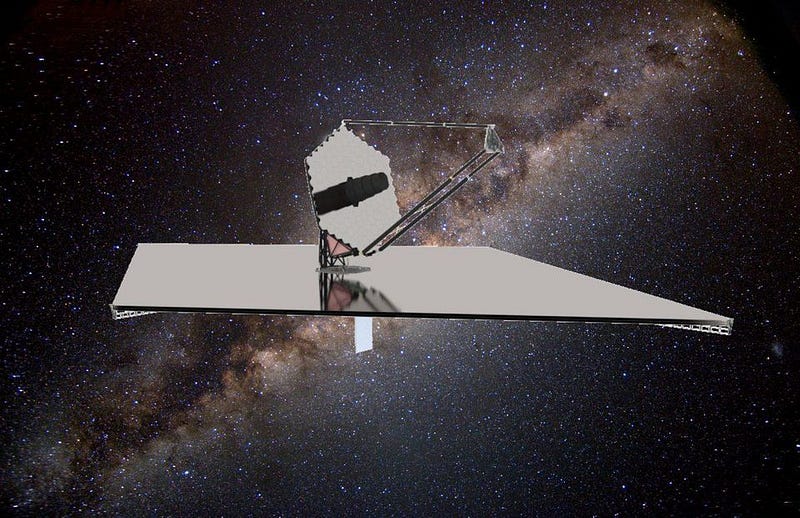

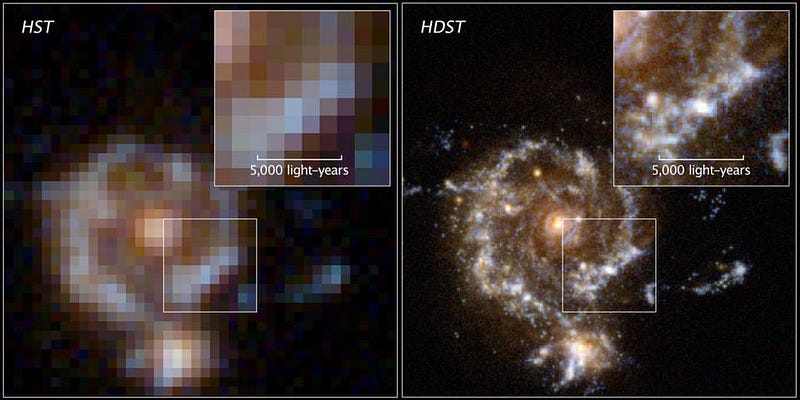

As an example, one of the proposals, LUVOIR, was designed to be the ultimate successor to Hubble: 40 times as powerful with a diameter of up to ~15 meters. It was designed to tackle problems in our Solar System, measure molecular biosignatures on exoplanets, to perform a cosmic census of stars in every type of galaxy in the Universe, to achieve the sensitivity capable of seeing every galaxy in the Universe, to directly image and map the gas in galaxies everywhere, and to measure the rotation of galaxies (and better understand dark matter) for every galaxy in the Universe.

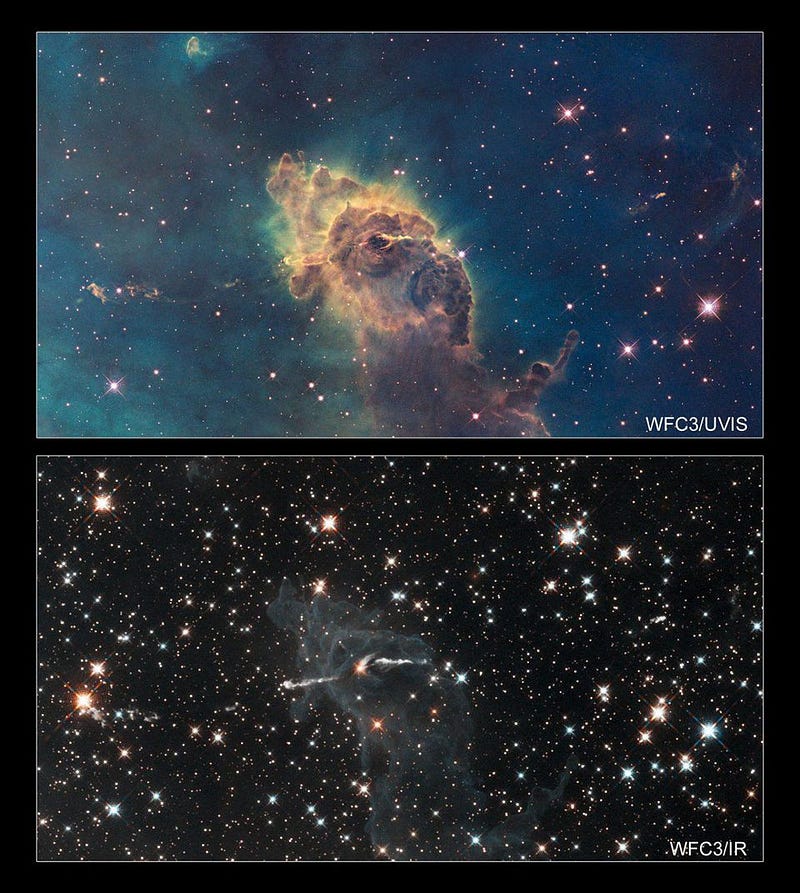

But the new architecture would be only half the diameter, half the resolution, and with a quarter of the light-gathering power of the original design. It would basically be an optical version of the James Webb Space Telescope. The sweeping ambition of the original project, with the potential to revolutionize our view of the Universe, would be lost.

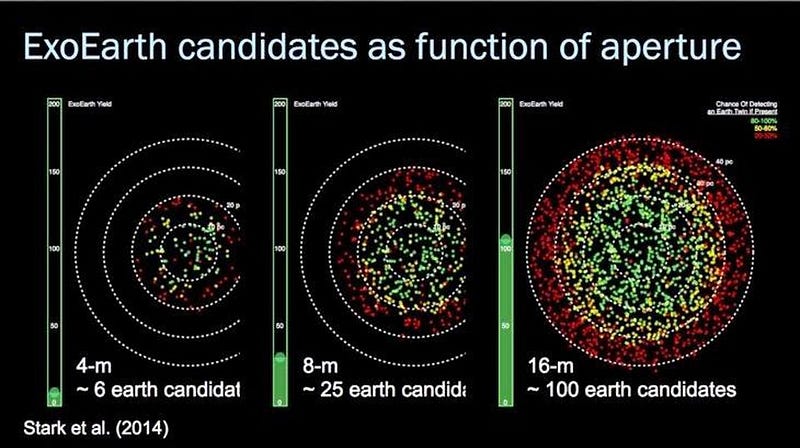

The other three proposals are more easily scaled-down, but again lose their power. HabEx, designed to directly image Earth-like planets around other stars, loses 87.5% of the interesting planets it can survey if its size is reduced in half. It might not offer much more than the other suites of missions that will fly, like WFIRST (especially if WFIRST gets a starshade), to justify being the flagship mission with such a reduction. LYNX, designed to be a next-generation X-ray observatory that’s vastly superior to Chandra and XMM-Newton, might not be much superior to the ESA’s upcoming Athena mission on such a budget. Its spatial and energy resolution were supposed to be its big selling points; on a reduced budget, it’s hard to see how it will achieve those.

The best bet might be OST: the Origins Space Telescope, which would represent a huge upgrade over Spitzer: the only other far-infrared observatory NASA’s ever sent to space. Its 9.1 meter design is likely impossible at that price point, but a reduction in size is less devastating to this mission. At a lower price tag, it can still teach us a huge amount about space, from our Solar System to exoplanets to black holes to distant, early galaxies. There is no NASA or European counterpart to compete with, and unlike the optical part of the spectrum, it’s notoriously challenging to attempt astronomy in this wavelength from the ground. The closest we have is the airplane-borne SOFIA, which is fantastic, but has a number of limitations.

This is NASA. This is the pre-eminent space agency in the world. This is where science, research, development, discovery, and innovation all come together. The spinoff technologies alone justify the investment, but that’s not why we do it. We are here to discover the Universe. We are here to learn all that we can about the cosmos and our place within it. We are here to find out what the Universe looks like and how it came to be the way it is today.

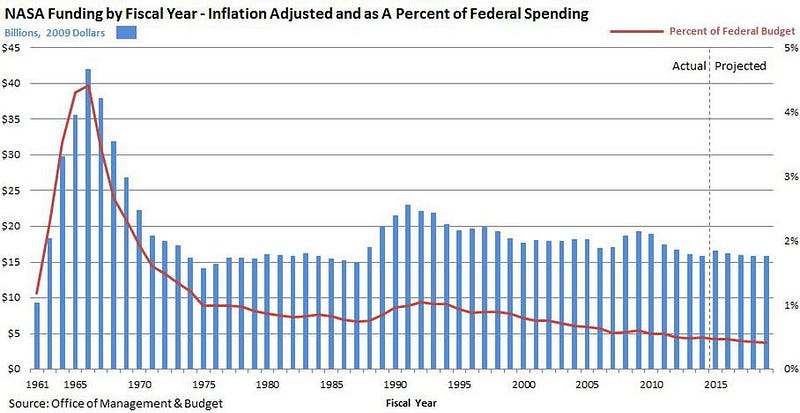

It’s time for the United States government to step up to the plate and invest in fundamental science in a way the world hasn’t seen in decades. It’s time to stop asking the scientific community to do more with less, and give them a realistic but ambitious goal: to do more with more. If we can afford an ill-thought-out space force, perhaps we can afford to learn about the greatest unexplored natural resource of all. The Universe, and the vast unknowns hiding in the great cosmic ocean.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.