Mystery solved: Ceres’ white spots are salt!

Not water, not ice, and definitely not aliens. Here’s how we know.

“You are the salt of the earth. But remember that salt is useful when in association, but useless in isolation.” –Israelmore Ayivor

Imagine it: for nearly 200 years after its discovery, Ceres was never more than a single point of light through even a powerful telescope. As telescopes and seeing improved — and finally with the advent of Hubble and digital CCD cameras — it became a fuzzy object some 17 pixels across at its closest approach to Earth. As the largest object in the asteroid belt, it was thought to be similar to other bodies of that size: made of rocky material, potentially with some ices and other sub-surface volatiles mixed into its interior.

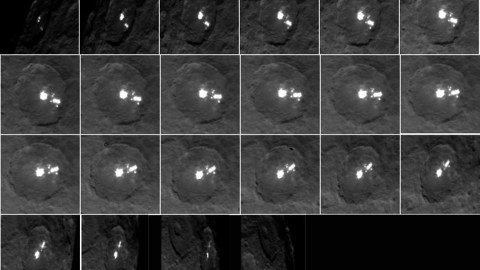

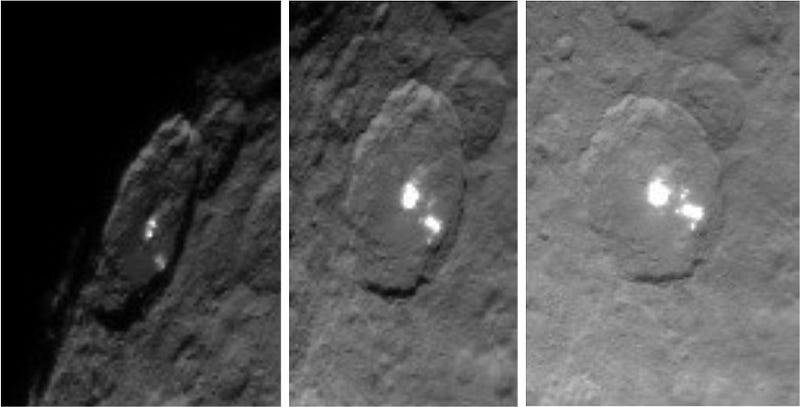

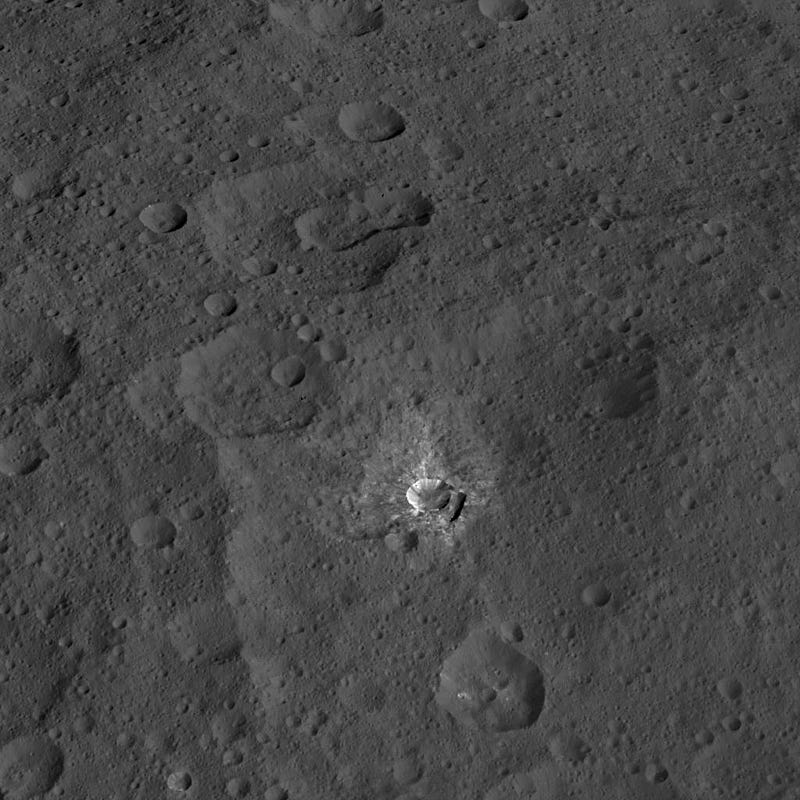

So imagine our surprise when we finally visited it with NASA’s Dawn mission, and saw the following inside one of its craters:

What an oddity! At the bottom of a crater — of a well-lit, full-on-in-the-sunshine crater — there lies what appears to be some bright material, farbrighter than the rest of Ceres’ surface. Immediately, speculation ran rampant:

- Could it be water-ice or some other frozen material, somehow notboiling/sublimating away in the sunshine?

- Could it be some type of strange, crystalline deposit, like salts?

- Or could it, perhaps, even be a self-luminous civilization — aliens — taking up residence at the bottom of this crater?

That last option could easily be ruled out by watching the crater rotate from night-to-day, and seeing if the light is really self-luminous, or simply reflective.

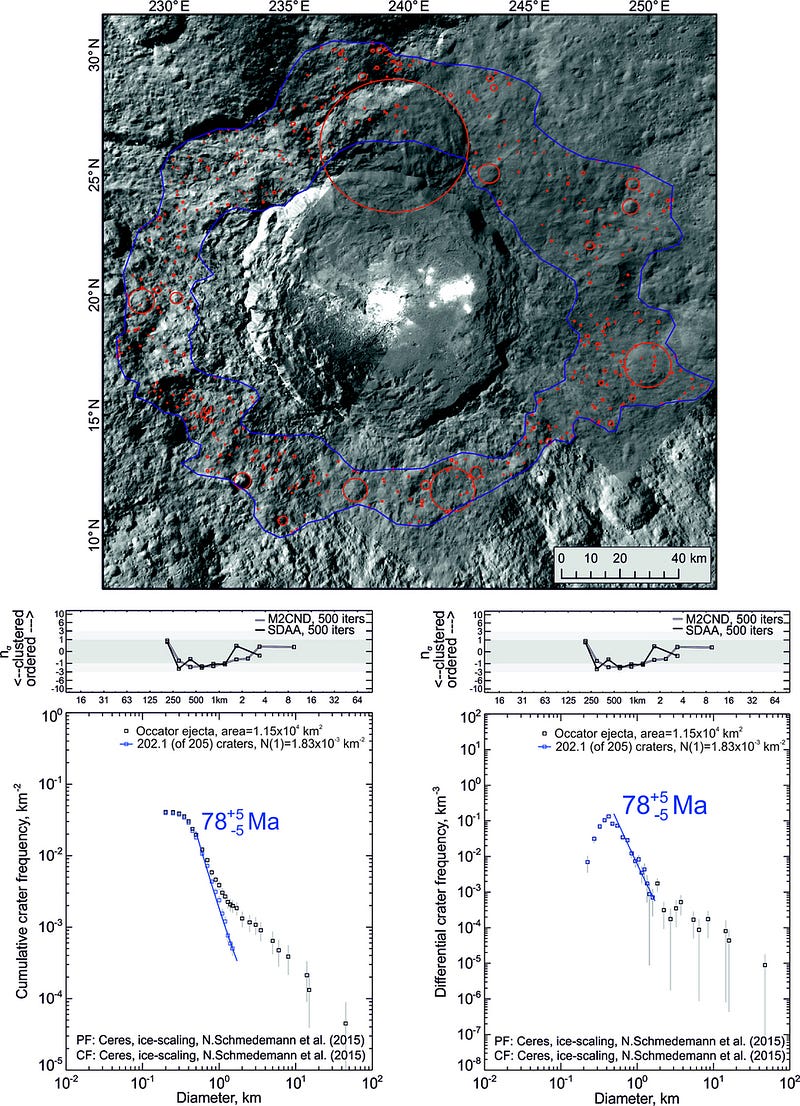

To no one’s surprise, it wasn’t aliens. What we were seeing was a region of the surface that was reflecting about 40% of the sunlight, in sharp contrast to the duller material coating the rest of the planet, which only reflects about 9%.

The way to find out what it was made of, unfortunately, couldn’t be done with visible images alone. It would require other instruments from the Dawn spacecraft to return their data, for that data to be analyzed, and for the chemical composition of this material to be determined.

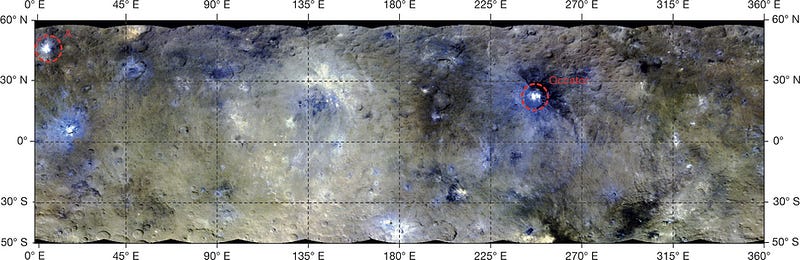

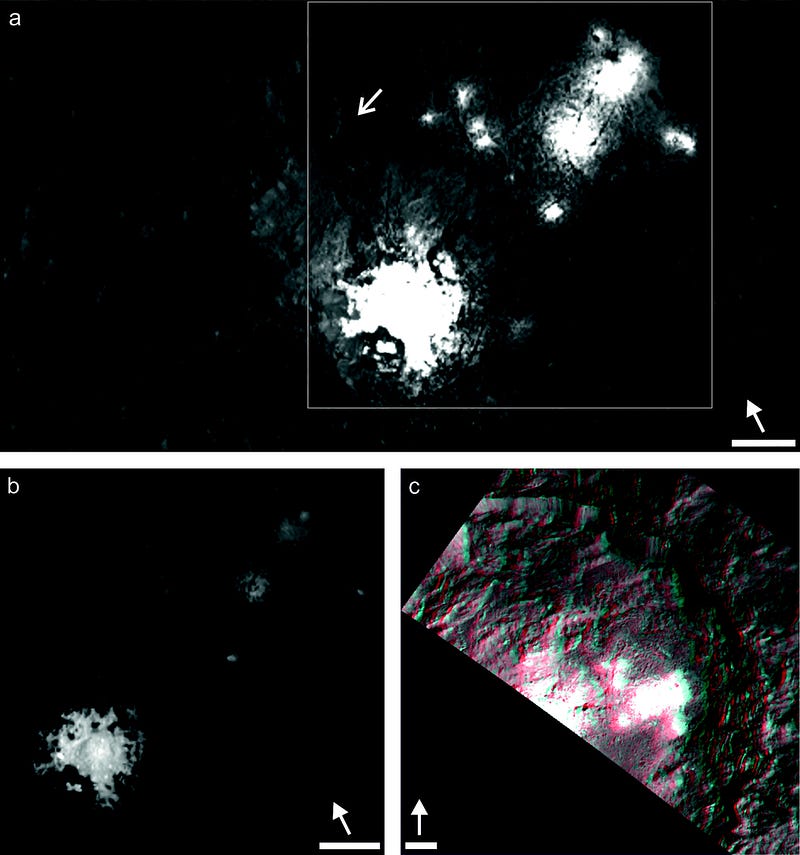

The blue “haze” you see extended over various regions of Ceres, above, actually is water, or more specifically, is a haze of water transitioning between the solid and the vapor phase. But you’ll notice that where that blue haze is the brightest is inside and surrounding Occator crater: the crater containing these mysterious bright spots.

But the bright spots themselves aren’t water ice at all!

Rather, the water vapor cools off at night when it’s hidden from the Sun, sinking back into the crater and flowing down to the low points. Water-soluble material — like salts — are carried with the water to the crater floors, where it freezes into ice crystals.

When day comes again, and the ice gets hit by the Sun, it sublimates back into the gaseous phase, leaving the salt flats behind.

There have likely been flows there, indicating the possibility of liquid water, at least temporarily, on the surface. This might seem unlikely at Ceres’ low pressures, but the presence of salt can drastically alter the range of pressures under which water can be a liquid. Exactly what type of salt this is hasn’t been revealed yet by the analysis thus far, but magnesium sulfate is speculated to be the likeliest culprit. Future data from a combination of many of Dawn’s instruments should give us an answer to that question as well in the coming months.

Now that we know this part of the story, there are two other big questions that come up.

One, of course, is about the second-brightest feature on Ceres: Oxo crater’s rim, shown at left, above. Is that salt as well, and was it brought there by the same process that created the deposits at the bottom of Occator crater?

The second is, where did this water-ice come from? It must have come from beyond the frost line in the Solar System, which Ceres is interior to. Given all this time, any water-ice on the surface of Ceres would be long gone by now, not producing an active haze.

Coupled with questions into the nature of this salt, what cratering process revealed it and why it hasn’t been resurfaced over yet, there’s plenty still left to learn. But the biggest mystery — the nature of these bright spots — is now solved: they’re reflective salt crystals. The rest is still yet to be discovered.

Leave your comments on our forum, help Starts With A Bang! deliver more rewards on Patreon, and pre-order our first book, Beyond The Galaxy, today!