Four scientific ways we can be certain the Moon landings were real

- Even though it’s been a half-century since humans set foot on the Moon, there’s overwhelming evidence that our trips to our lunar neighbor were not faked.

- The lunar landing sites have been imaged repeatedly, more than 8,000 photos from those journeys have been publicly released, and hundreds of pounds of lunar samples have been brought back to Earth.

- Moreover, the scientific equipment that we installed there not only remains, but is still actively in use. Humanity’s historical presence on the Moon cannot be denied.

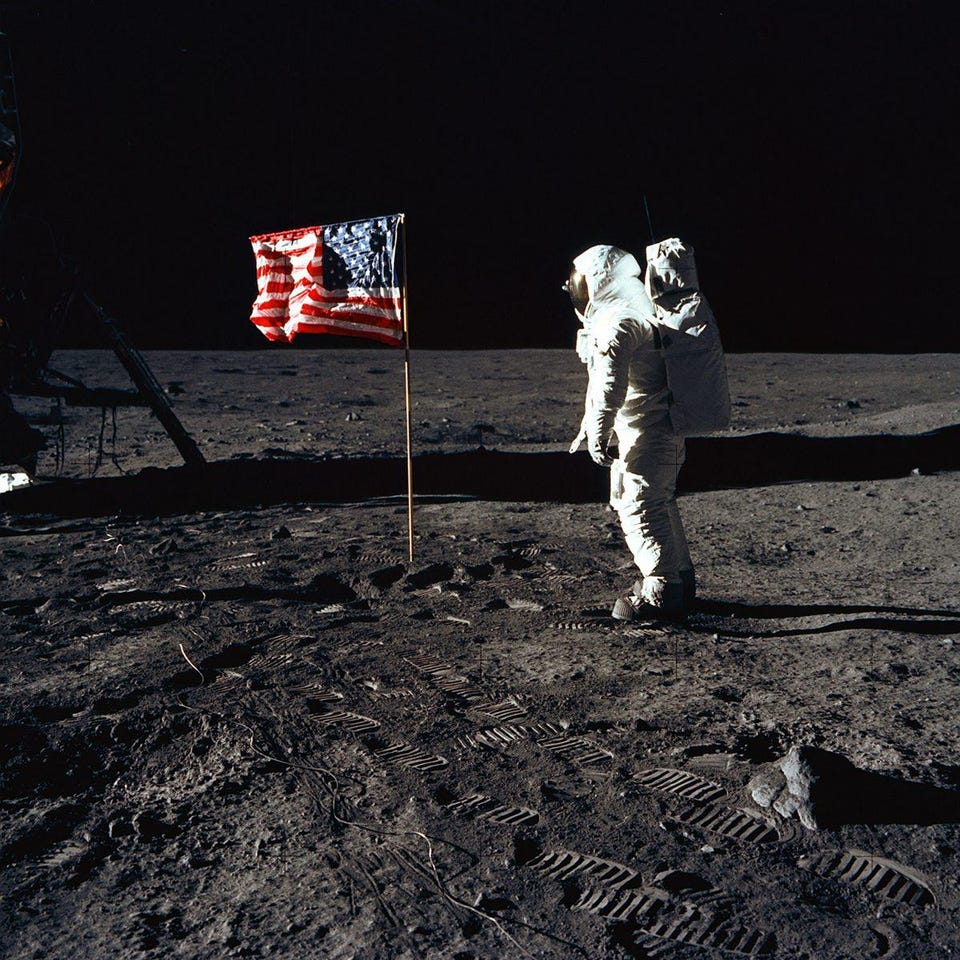

In all of human history, only 24 people have ever flown to the vicinity of the Moon, traveling hundreds of thousands of miles from Earth to do so. Twelve of those people, on six independent missions, actually set foot on the lunar surface. We’ve left behind flags, photographs, seismometers, mirrors, and even vehicles, and we’ve brought back rocks, dirt, and actual pieces of the Moon.

Most people alive today don’t have memories of these monumental moments in history, of landing on the Moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Unsurprisingly, some of them are skeptical that it ever happened. Thankfully, in science, we don’t need to be there ourselves to have proof. Here are four different pieces of evidence we can point to that demonstrate the Moon landings actually occurred.

1.) Lunar footprints. Here on Earth, footprints generally don’t last very long. Wherever you leave your tracks, you fully expect that natural phenomena will eventually cover them up, whether it takes minutes, days, or weeks. Winds blowing along the sand dunes, rains in the forest, or plant and animal activity will eliminate the evidence of your tracks over time.

This happens for a variety of reasons, such as that Earth has:

- an atmosphere

- weather

- liquid water on our surface

- living species

So, if we walked on the Moon, we would expect our footprints to remain there. Without winds, rains, snows, glaciers, rockslides, or any other means of moving and rearranging the particles on the surface of the Moon, any footprints that we make should remain for an interminable length of time. The only rearrangement of lunar sand and grains that we know of occurs when objects collide with the Moon and kick up dust, which can then settle across the lunar surface.

Sunlight striking these particles is inefficient; the lunar atmosphere is only approximately one atom thick; launch and lander activity isn’t energetic enough to substantially alter the distribution of material on the Moon. If we ever landed and traveled on the Moon, the evidence should still be there.

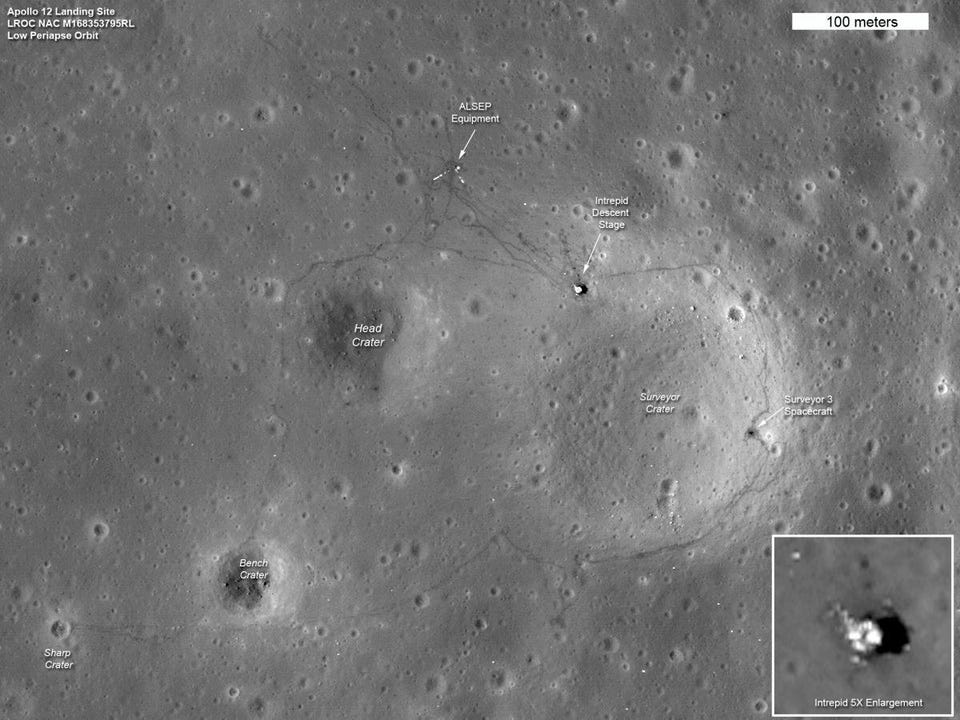

NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has orbited and mapped the Moon at the highest resolution ever, returning hundreds of Terabytes of data, has something to say about that.

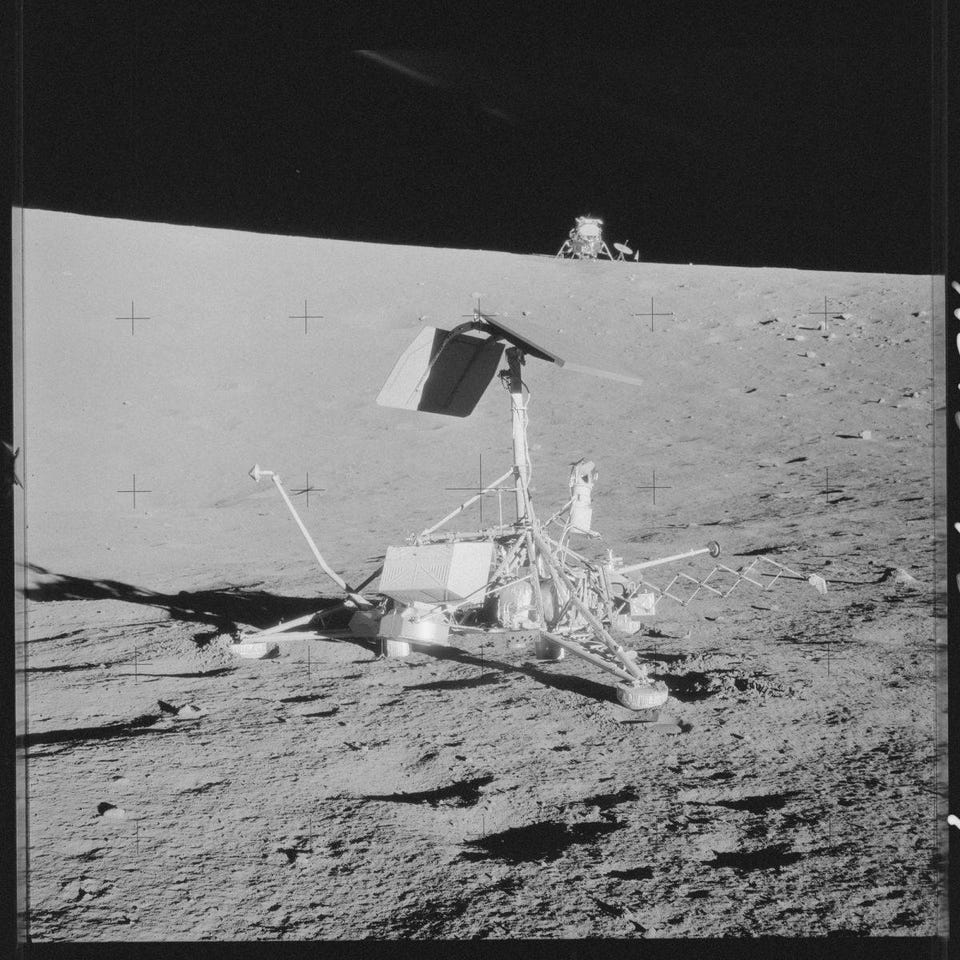

Credit: NASA/LRO/GSFC/ASU

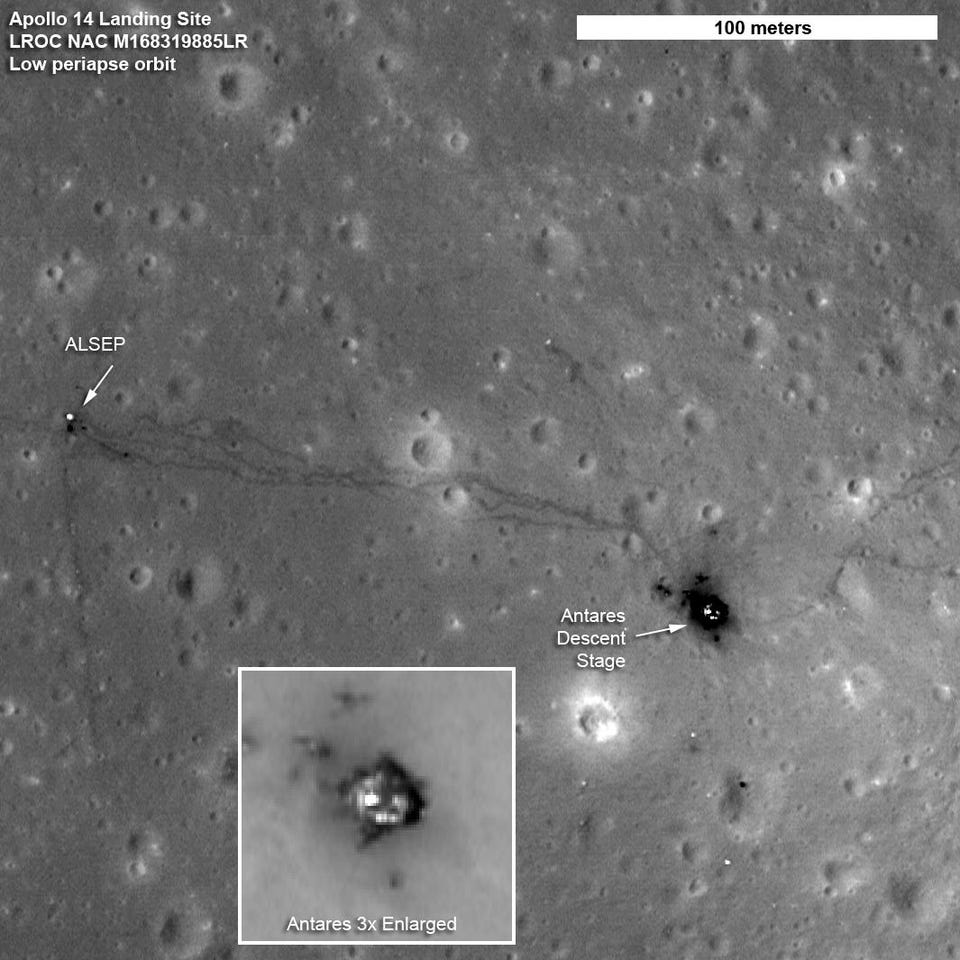

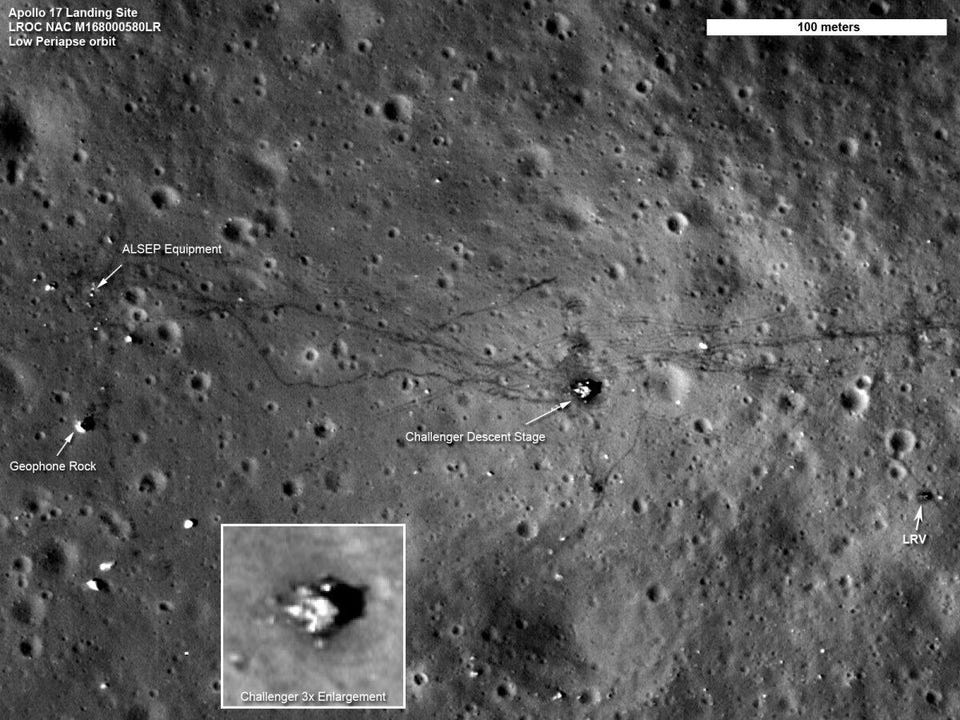

The orbiter’s Narrow Angle Camera has photographed three of the landing sites — of Apollo 12, 14, and 17 — to unprecedented precision and accuracy. By going close to the lunar surface and photographing it with modern instruments from that low altitude, they were able to achieve resolutions as low as 35 centimeters (about 14 inches) per pixel.

The Apollo 12 image shows not only the physical landing site (marked “Intrepid Descent Stage” on the image), but also the Surveyor 3 probe that had been on the Moon since 1967, visited by the Apollo 12 astronauts two-and-a-half years later! There’s the bright, white “L” shape near the ALSEP equipment label; the “L” is due to highly reflective power cables that run from the central station to two of its instruments.

And finally, the dark paths that look like dried-up canals? Those are astronaut footprints.

The view of Apollo 14 is less spectacular, but perhaps even more famous. You can still see the descent module and the ALSEP equipment, but nothing else leaps out at you. Well, except for the footpaths once again! Who made them? Edgar Mitchell and the famed Alan Shepard.

Although we never found the golf balls that Alan proclaimed went “miles and miles” when he hit them with a 6-iron, we can absolutely see the evidence of the astronauts’ presence left behind on the Moon, nearly 50 years later.

Apollo 17, where Eugene (Gene) Cernan and Harrison (Jack) Schmitt became the last men to walk on the Moon, paints a notably different picture at this high resolution. Yes, there’s still the descent module on the surface, the ALSEP equipment and the footpaths. But look closer: There’s also something marked “LRV” as well as a lighter set of two parallel tracks that run across the surface. Know what they are?

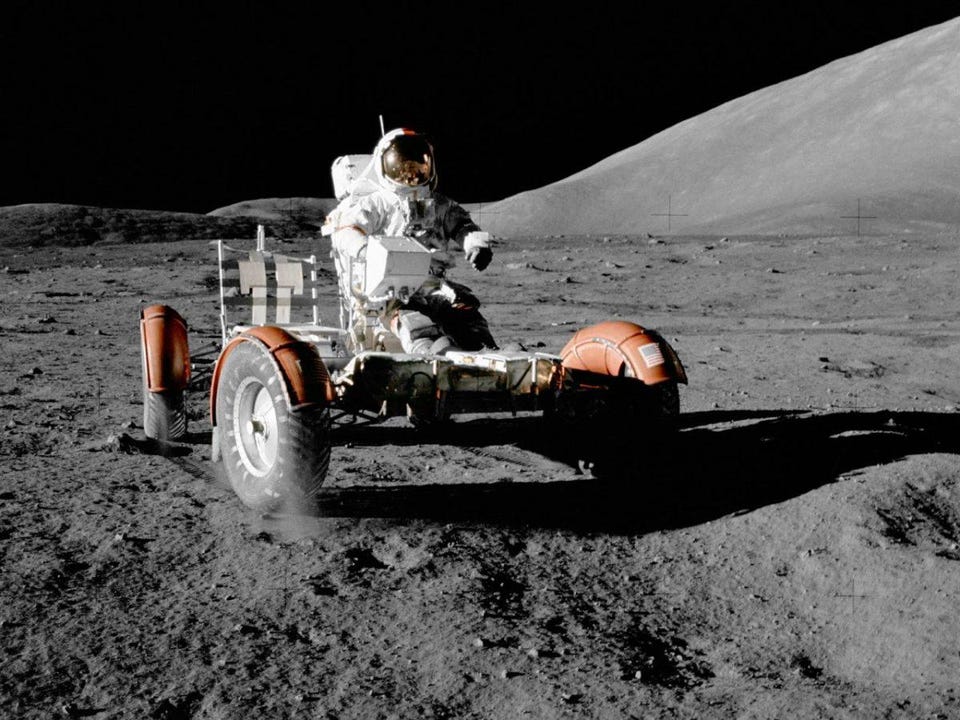

Credit: NASA/Jack Schmitt/Apollo 17

The Apollo Lunar Roving Vehicle! Included on Apollo 15, 16, and 17, its tracks on the surface are distinctly different from human footprints, and allowed the astronauts on those missions to achieve distances far greater than those reached on the earlier missions. The tracks from Apollo 17’s LRV don’t even come close to fitting in this image; they extend for a total distance of over 22 miles, reaching a maximum range of nearly five miles away from the landing site!

And yet, all of that copious, substantial evidence that we can still see on the Moon represents only one part of the four major lines that demonstrate the veracity of our trips to our nearest neighbor.

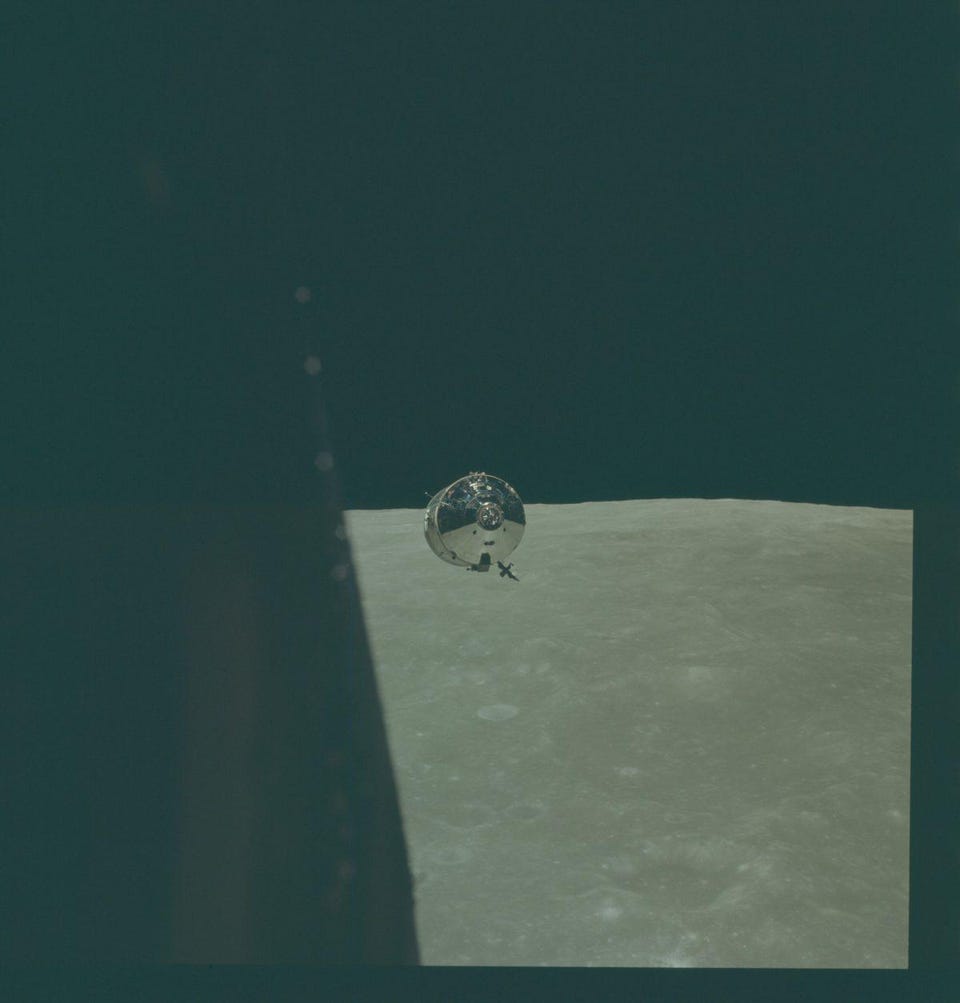

Credit: NASA/Apollo 10

2.) Over 8,000 photos documenting our trips. Perhaps we all need a reminder of what the sacrifices were that went into our journey to the Moon. We accomplished the unthinkable by banding together to achieve a common goal, and could do it all once again. NASA has released all the photos of the twelve Apollo missions that made it to space on a publicly available Flickr photostream, sorted into a series of incredible albums by mission.

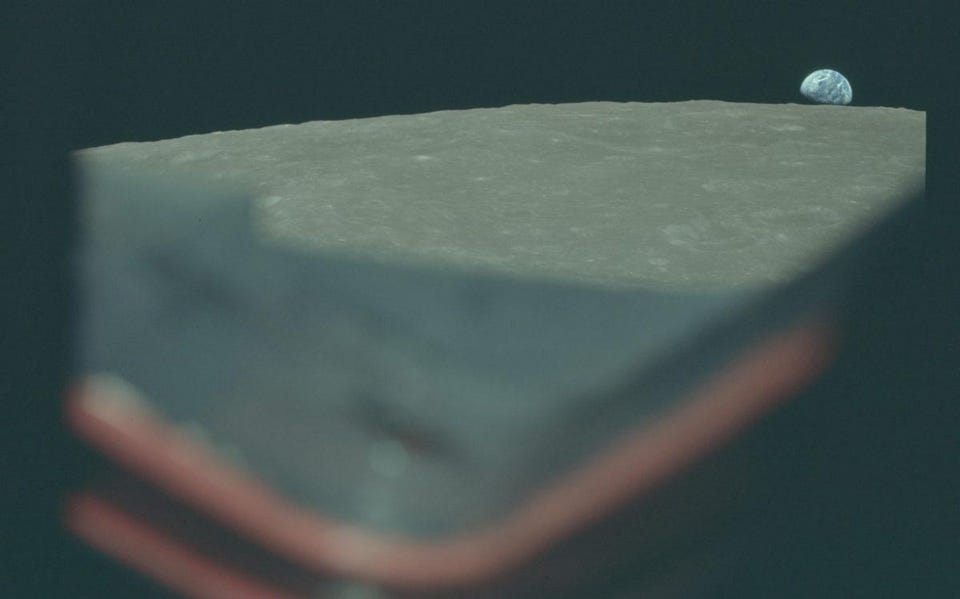

Some of the greatest and most eye-opening photos, stories, and quotes came back from those trips, including some from Apollo 8’s Bill Anders, who took not only the famous “Earthrise” photo that was sent around the world in late 1968, but also a series of photos showing the Earth rising over the limb of the Moon, as illustrated above. Anders described the journey to the Moon as follows:

“You could see the flames and the outer skin of the spacecraft glowing; and burning, baseball-size chunks flying off behind us. It was an eerie feeling, like being a gnat inside a blowtorch flame.”

3.) Scientific equipment we’ve installed on the Moon. Did you know that we brought up a large amount of scientific equipment and installed it on the lunar surface during the Apollo missions?

- Lunar seismometers were installed by Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, and 16, with the most advanced ones transmitting data to Earth until 1977.

- Apollo 11 installed the lunar laser ranging retroreflector array, which is still operational today, allowing us to reflect lasers off of it and measure the Earth-Moon distance to ~centimeter precision. (We also use Apollo 14, 15, and the Soviet Lunokhud 2 rover for this.)

- The SWC experiment, to measure the solar wind composition from the Moon’s surface.

- The SWS experiment to measure the solar wind’s spectra from the Moon.

- The LSM experiment to measure the lunar magnetic field.

- The LDD to measure how lunar dust would settle on and pollute solar panels.

And many others. That we have the data from these experiments, and that the lunar retroreflectors are still in use today, represents some pretty strong evidence that we did, in fact, land on the Moon.

Credit: NASA/David Harland

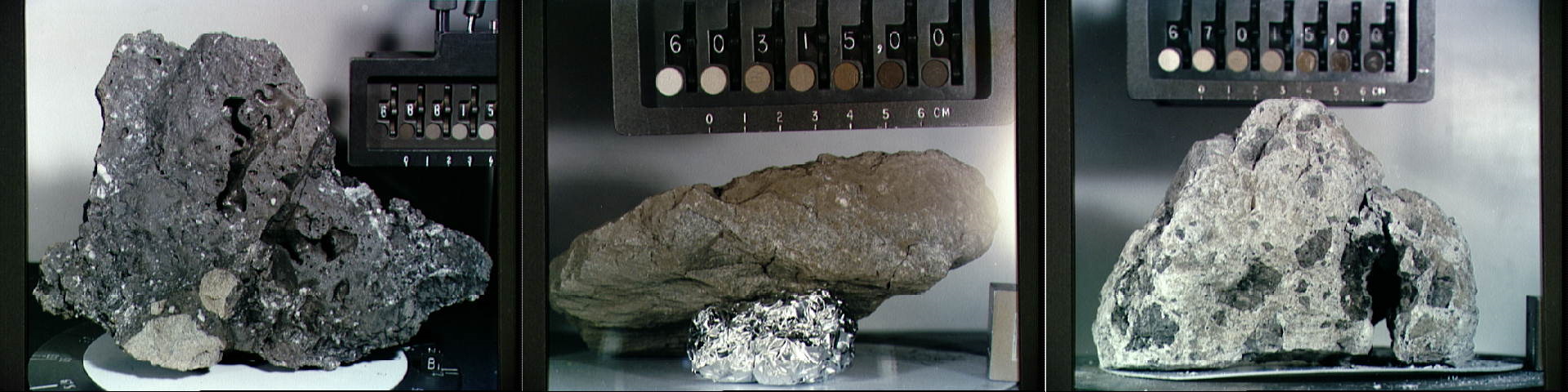

4.) We brought back samples, and learned a ton about lunar geology from them. The final two astronauts to ever walk on the Moon, Gene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt, ran into quite a surprise when they did. Schmitt, the lone civilian-astronaut (and only scientist) to travel to the Moon, was often described as the most business-like of all the astronauts. That’s why it must have been such a shock to hear him exclaim the following:

“Oh, hey! Wait a minute… THERE IS ORANGE SOIL! It’s all over! I stirred it up with my feet!”

The dull, grey lunar soil you’re used to seeing — that we’re all used to seeing — in one particular spot was only a very thin veneer, covering a rich, orange landscape beneath.

Like any good scientist, or any good explorer, for that matter, Cernan and Schmitt took pictures, collected data, and brought samples back to Earth for further analysis. What could cause orange soil on the Moon, perhaps the most featureless of all the large, airless rocks in our Solar System?

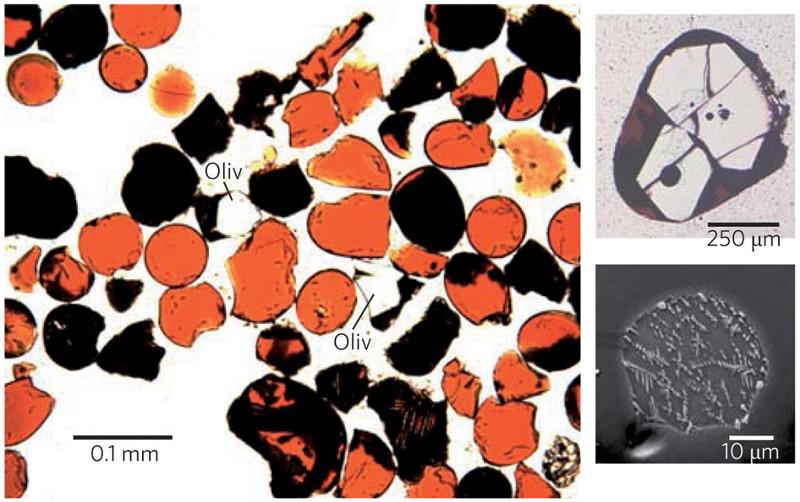

What the analysis back on Earth revealed was fantastic: this was volcanic glass. What occurred was that molten lava from the interior of the Moon erupted, some 3 to 4 billion years ago, up above the airless surface and into the vacuum of space. As the lava became exposed to the vacuum, it separated out into tiny fragments and froze, forming tiny beads of volcanic glass in orange and black colors. (The tin in some of the fragments is what gives the orange color.)

In 2011, reanalysis of those samples found evidence that water was included in the volcanic eruption: with concentrations of water in the glass beads that were formed 50 times as great as the expected dryness of the Moon. Olivine inclusions showed water present in concentrations up to 1,200 parts per million.

Most remarkably, the lunar samples we’ve found indicate that the Earth and the Moon have a common origin, consistent with a giant impact that occurred only a few tens of millions of years into the birth of our Solar System. Without direct samples, obtained by the Apollo missions and brought back to Earth, we never would have been able to draw such a startling, but spectacular, conclusion.

There are many different lines of evidence that point to humanity’s presence on the Moon. We landed there and can see the evidence, directly, when we look with the appropriate resolution. We have extraordinary amounts of evidence, ranging from eyewitness testimony to the data record tracking the missions to photographs documenting the trips, all supporting the fact that we landed and walked on the lunar surface. We have a slew of scientific instruments that were installed and took data, a few of which can still be seen and used today. And finally, we’ve brought back lunar samples and learned about the Moon’s history, composition, and likely origin from it.

There are many ways to prove it, but the conclusion is inescapable: We really did land on the Moon, and we can validate it yet again by performing the right scientific test — through imaging or laser ranging — any time we want.