Messier Monday: Virgo’s Final Galaxy, M100

It’s the last Virgo Cluster member in the entire Messier catalogue, but they saved the best for last!

Image credit: European Southern Observatory (ESO), via http://www.eso.org/public/images/eso0608a/.

“From a little spark may burst a flame.” –Dante Alighieri

For nearly two years, now, every Monday here on Starts With A Bang has been Messier Monday. For centuries, the primary goal of most astronomers was to hunt for comets, as the wonders of other planets, galaxies, and deep-sky objects was unknown: just the Moon, stars, naked-eye planets and the Milky Way. The comets were thought to be the only interesting things up there! There were only a few fixed, deep-sky objects that were known. In the 1700s, Charles Messier began compiling the first large-scale catalogue designed to keep track of the brightest ones, recording their positions and descriptions, so that potential comet-hunters wouldn’t be confused.

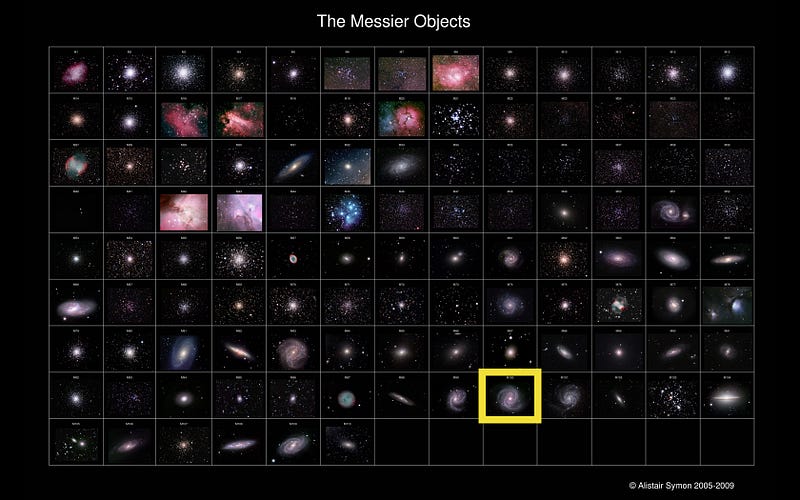

The result was the Messier catalogue, which stands today at 110 objects, and is incredibly useful as a catalogue of objects — ranging from nebulae to clusters to galaxies — that are prominent as viewed from Earth. (And particularly from northern latitudes.) There are 40 galaxies in Messier’s catalogue, by far the most of any type, including a whopping fifteen found in the Virgo Cluster, which is now known to boast over 1,000 member galaxies. The last and, perhaps, most spectacular of these is Messier 100, today’s object. Here’s how to find it.

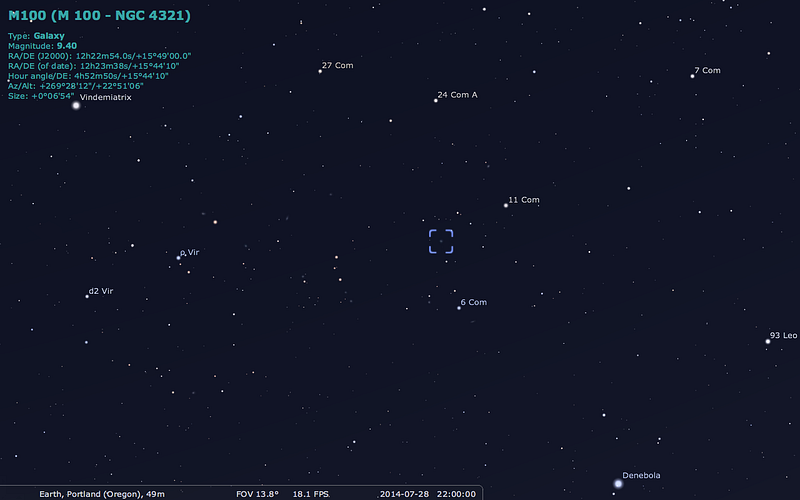

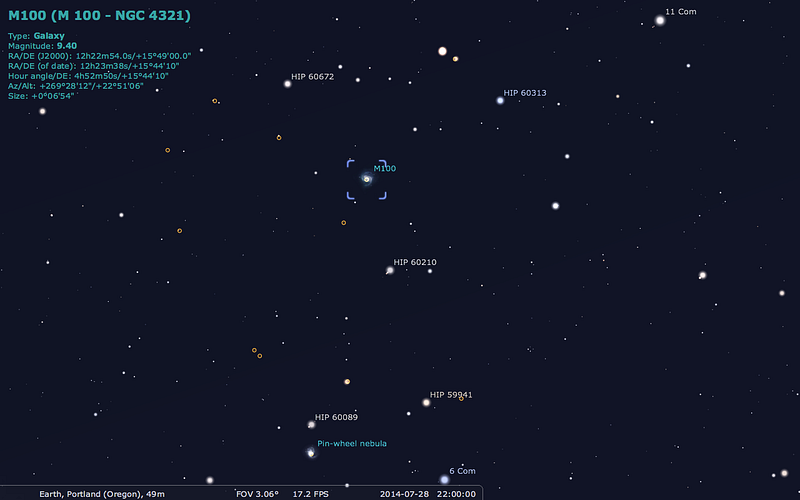

After sunset in the summer skies, the Big Dipper looms prominently overhead, with the constellation of Leo floating directly “below” the handle-and-cup of the dipper. Although it’s low above the horizon, the bright star Denebola should be shining clearly at the eastern end of this constellation, with the bright Vindemiatrix a little bit farther away, standing out against a dark region of sky.

It’s between these two stars — Denebola and Vindemiatrix — that you need to look to find Messier 100.

If you drew an imaginary line connecting these two stars, you’d find two naked-eye stars along the line: ρ Virginis closer to Vindemiatrix and just below the imaginary line, with 6 Comae Berenices closer to Denebola and just above that same line. In an arc above 6 Comae Berenices lies three other naked-eye stars, but you don’t need to go that far.

In fact, if you navigate just a little bit north of it, two barely perceptible naked-eye stars — easily visibly through binoculars — will unmistakably point your way to Messier 100.

It was discovered by Messier’s assistant, Pierre Méchain, in March of 1781, and confirmed four weeks later by Messier himself, who recorded it as:

Nebula without star, of the same light as the preceding [Messier 99], situated in the ear of Virgo. Seen by M. Méchain on March 15, 1781. These three nebulae, nos. 98, 99 & 100, are very difficult to recognize, because of the faintness of their light: one can observe them only in good weather, & near their passage of the Meridian.

Intrinsically, this is actually quite a bright galaxy, but at its distance of 55 million light-years — and with its brightness distributed over a very large area — it will very likely “only” look like this through a good telescope today.

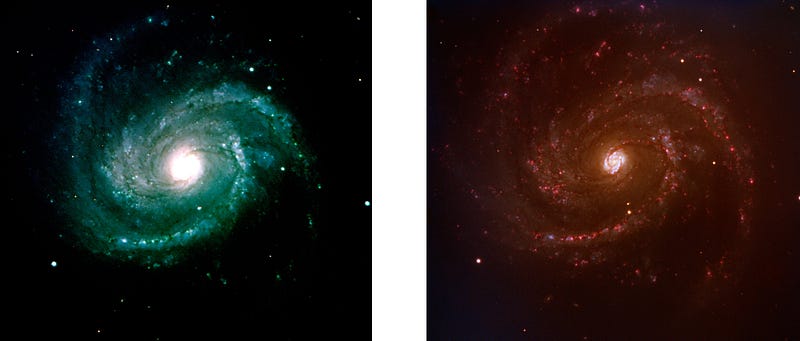

The spiral structure in it wasn’t observed until 1850, where M100 became one of the 14 original galaxies identified to have a spiral structure. This galaxy is also the poster child of one of the most famous images in all of astronomy. You see, when the most famous telescope of our time — the Hubble Space Telescope — was first launched, it was outfitted with a defective mirror! The first servicing mission, three years later, fixed this problem, and the before-and-after images of Messier 100 show perhaps the clearest indication of the improvement in the telescope’s overall performance.

Like many galaxies in the Virgo Cluster, an incredibly rich region of space where galaxies whip through the intergalactic medium at more than 1,000 km/s, Messier 100 has had large amounts of its gas stripped away. It’s also in the process of merging with two dwarf satellite galaxies. The combination of these effects, as well as the gas being funneled in towards the center, give rise to a burst of star formation both along the spiral arms (where blue stars stand out) and also in the bright central region!

As with many well-positioned galaxies, we can look in multiple different wavelengths to learn all sorts of things about this one. Looking in the optical tells us about the populations of the stars inside, and we can conclude that the last 500 million years have given rise to a very recent spike in new stars; the blueness of the arms shows us that immediately.

The infrared, on the other hand, traces out the location of cool gas; this is the material that will form the next generation of stars in this galaxy!

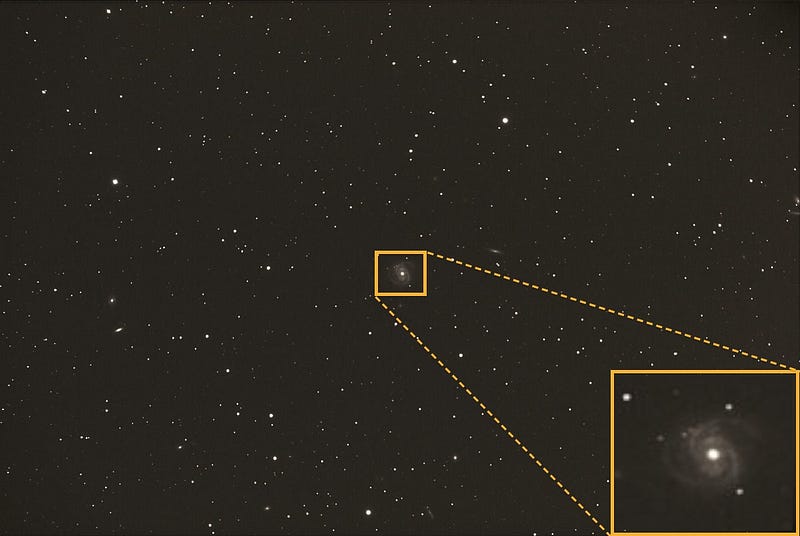

Galaxies undergoing recent bursts of star formation tend to give rise to larger numbers of supernovae, and Messier 100 does, in fact, follow that rule. Since the dawn of the 20th Century, we’ve observed five separate supernovae events, most recently in 2006, where a bright light appeared and then faded, visible in the image below at right (but not at left). The “extra light” is visible below the central nucleus and just below a foreground star from our own galaxy.

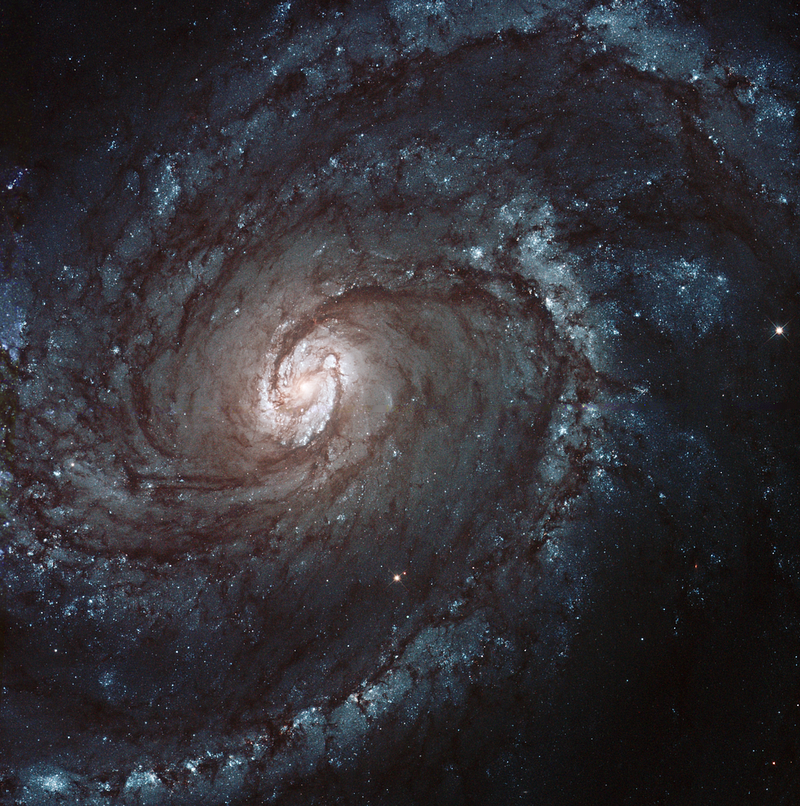

A close-up view of the central region showcases the dust lanes, a bar-like structure (essential for funneling gas towards the core), and many other interesting features.

If we confined ourselves to a very specific wavelength of light — 656.3 nanometers — we would begin to highlight where ionized hydrogen gas is combining with free electrons to form neutral hydrogen, something that only happens around very hot regions, or regions where new stars are forming.

Want to see where that is?

All along the spiral arms, and in clusters where the blue stars shine brightest!

Flickr user Judy Schmidt did some processing with a combination of visible and ultraviolet images from Hubble to create the following fantastic composite, really showcasing the dust lanes in the core region of this galaxy.

It’s still amazing to me that, from 55 million light-years away, we can resolve individual stars in this distant, island Universe. Messier 100 is not so different from our own galaxy, similar in mass, size (maybe 7% bigger). It even has smaller, satellite galaxies like we do, and its major differences are simply the larger rate of recent star formation and the smaller amount of neutral gas, both of which are a consequence of its location inside the Virgo Cluster!

As always, my favorite image of this comes from the Hubble Space Telescope; even though I’ve shown you a couple of those already, we’ve imaged this beautiful wonder many times!

And that’s the glory of the final Messier galaxy in the Virgo cluster! With that behind us, have a look back at all our previous Messier Mondays:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back next week, where the presence of the Moon in the sky won’t keep us from exploring another deep-sky wonder here on Messier Monday!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs.