Messier Monday: The Teapot-Dome Cluster, M28

At the top of the Teapot, a fantastic cluster dotted with Red Giants awaits.

Image credit: © 2005–2009 by Rainer Sparenberg, via http://www.airglow.de/html/starclusters/m28.html.

“The most difficult thing is the decision to act, the rest is merely tenacity. The fears are paper tigers. You can do anything you decide to do. You can act to change and control your life; and the procedure, the process is its own reward.” –Amelia Earhart

As the northern hemisphere’s summer draws to a close, one of the last lingering remnants of this time of year are the stars, constellations and deep-sky wonders visible from Earth. Even as the days shorten and the Earth continues its orbit around the Sun, the nights arrive earlier, providing skywatchers with an opportunity to spy many summer sky delights that you might not have been able to wait up for in June and July.

While the more extended objects — star-forming nebulae, stellar remnants and distant galaxies — are difficult to make out during a night with a full Moon like tonight’s Supermoon, the open star cluster and the ancient globular clusters contained within our galaxy still make for spectacular sights through a telescope. If you head outside and look towards the southern horizon just after the sky darkens, some spectacular sights await, including Messier 28, the lucky subject of our attention tonight.

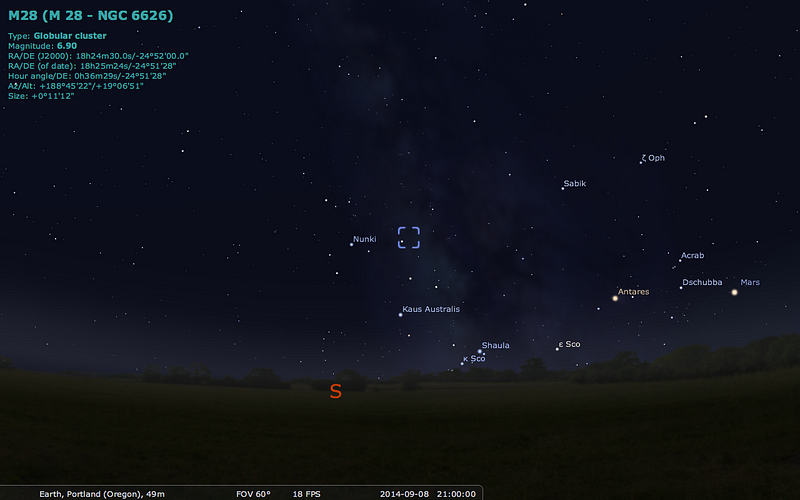

For today’s Messier Monday, look towards the teapot in Sagittarius, home to the highest density of star clusters in our Milky Way, and containing the galactic center.

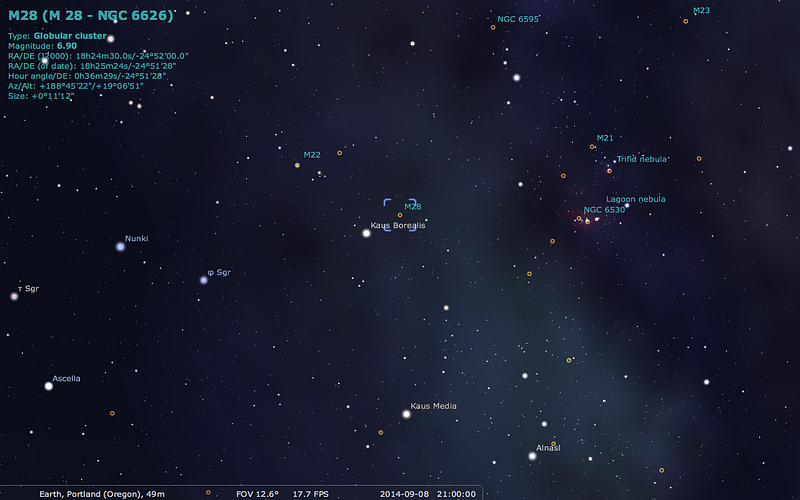

A collection of eight stars stands out in this region of the sky, not because they’re the brightest stars around, but because they have a distinctive pattern to them that we recognize as very similar to a common object here on Earth. We call such a collection of stars an asterism, and the teapot is one of the most recognizable ones. And the star at the very top of the teapot’s lid — Kaus Borealis — has a secret less than a single degree away from it.

Just slightly to the west of this star lies the globular cluster Messier 28, an authentic discovery of Messier himself back in 1764, or 250 years ago. It’s quite small, and although its core is concentrated, there’s a rich star field that it’s up against. (No surprise, considering how close we are to the galactic center here.) Nevertheless, there’s a star just a little farther along to the west that’s just barely visible to the naked eye: HIP 89980. If you can find that — in addition to Kaus Borealis — Messier 28 will simply pop out in your field-of-view.

As Messier himself described it:

Nebula discovered in the upper part of the bow of Sagittarius at about one degree from the star Lambda & little distant from the beautiful nebula which is between the head and the bow. It contains no star; it is round, it can only be seen difficultly with an ordinary telescope…

But, of course, an “ordinary telescope” in the hands of an amateur is far superior to what Messier had at his disposal all those centuries ago.

What appeared to Messier as a round, starless nebula is clearly a dense collection of stars that gets even more concentrated towards the center. What might not be obvious from just a glimpse is that, while the stars littered across the field in the image above range from hundreds to a few thousand light-years away, the stars of this cluster itself are 18,000 light-years distant!

The dust lanes of the galaxy are clearly visible in a wide-field, long-exposure image, but what makes Messier 28 so remarkable is that contained within a sphere just 30 light-years in radius — and remember, there are only about 400 stars within about 30 light-years of the Sun — is that there are at least fifty thousand stars in there, with a combined mass of around 550,000 Suns!

In addition, globular clusters like this one are old, with the stars in there containing just 5 percent the heavy metals of our Sun and having an age of around 12 billion years, or more than double the age of our Solar System.

While our Sun orbits the Milky Way’s center in a giant ellipse, the other globular-and-star clusters move about along their own paths, with the globular clusters’ motion often having very little to do with the motion of the galaxy in general. That’s why it’s such an odd coincidence that, with respect to us, Messier 28 is nearly perfectly stationary, with a redshift away from us that corresponds to a motion of just one kilometer-per-second.

What you might find interesting is that, when we look at the individual stars inside — and the brightest are magnitude +15, so break out your large-aperture telescopes — they’re exclusively red giant stars!

But where there are no blue stars (save the stragglers that form recently from low-mass stars merging), there are bound to be remnants of those initial high-mass stars that burned through their fuel ages ago. In particular, that should mean that neutron stars and black holes remain, and Messier 28 is not only home to the very first millisecond pulsar ever discovered in a globular cluster (back in 1986), but of all the globular clusters ever scanned for pulsars, Messier 28 contains the third most, and most of all among Messier objects.

In fact, here’s that very first one — PSR 1821–24 — as it emits X-rays in “pulses”, as imaged by Chandra!

This globular is a little more concentrated than most towards the center, rating a concentration class of IV (on a scale of I to XII), and as evidenced by the fact that Messier marked this cluster as having a radius just 20% of what it actually is!

There’s a great image from Hubble’s old WFPC2 camera that captures this, along with the brilliant red giants found inside.

But there was an even better Hubble image taken later that I think really highlights just how spectacular this cluster is at its core. Have a look, courtesy of the Hubble Legacy Archive, at a slice through this cluster in unparalleled full-resolution!

At this age, only Sun-like stars (and redder) are left, save the blue stragglers and the giant, evolving stars. There’s no better view of this cluster than from Hubble, and so with that, we’ll come to the end of another Messier Monday! Take a look back at all the previous objects we’ve covered, with today’s bringing us up to ninety-nine:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M19, The Flattened Fake-out Globular: August 25, 2014

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M28, The Teapot-Dome Cluster: September 8, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M69, A Titan in a Teapot: September 1, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back next week, when we’ll pass the triple-digits mark, and then the week after, when we’ll begin counting down the final ten objects, all visible in your night sky!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!