Messier Monday: The could-be-better cluster, M26

Messier himself lamented his own original discovery. If only he knew why he was so disappointed, he might’ve been amazed instead!

“Things need not have happened to be true. Tales and adventures are the shadow truths that will endure when mere facts are dust and ashes and forgotten.” –Neil Gaiman

Forming new stars in the Universe is a dangerous game for an atom. You have to get together with thousands upon thousands of solar masses of other atoms to even get a fighting chance, and even then — even if your clouds collapses to form stars — it’s a long shot that you’ll be in one. Most likely, you’ll be part of the interstellar medium that’s blown off back into the abyss of space by ultraviolet radiation from the hottest, largest, first-formed stars. But not always.

This Messier Monday, we take a look at one of the most common types of deep-sky object in the night sky, an open star cluster, but one that has an exceedingly rare property to it: despite being more than old enough that all its dust should have been blown off, there’s a tremendous amount of light-blocking material dimming the center of it!

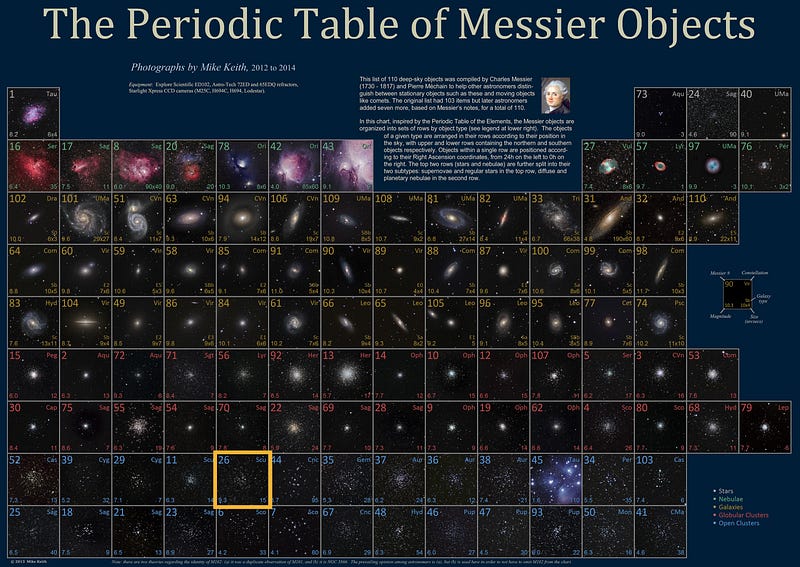

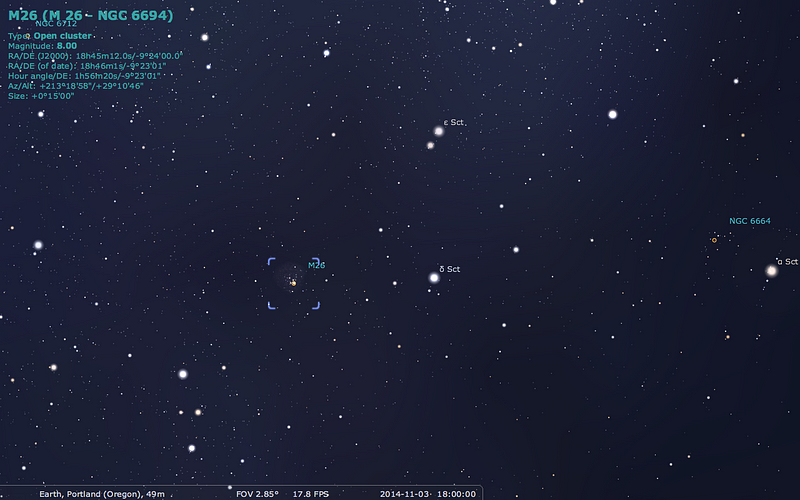

Today’s object was one of the original, relatively early discoveries of Messier himself way back in 1764: the open cluster Messier 26. Here’s how to find it.

Now that daylight savings time has finally ended, the night sky — particularly at high northern latitudes — tends to get dark out very early. By 6 PM where I am, we’re immersed in the near-total darkness of night. While the summer triangle still shines overhead despite being halfway to winter, the teapot of Sagittarius is only barely still visible over the southwestern horizon, where tonight, the planet Mars just happens to coincide with the “top” of the teapot’s dome: Kaus Borealis.

If you follow a curve of stars from Kaus Borealis up toward Altair, the southernmost vertex of the summer triangle, you’ll be well on your way to Messier 26.

A series of naked-eye stars curve up and slightly to the west, then break back towards Altair if you start from the top of the teapot’s dome. The westernmost among them is the relatively bright orange star α Scuti, approximately 40% of the way up towards Altair. Just to the east of α Scuti are two other naked-eye stars: δ Scuti and ε Scuti, with δ Scuti lying slightly south.

Connect α Scuti to δ Scuti and continue on just a fraction of a degree, and Messier 26 will be easy pickings for you.

Messier himself couldn’t even find it through his standard telescope, saying:

A cluster near Eta and Omicron in Antinous [now Alpha and Delta Scuti], between which there is another one of more brightness: with a telescope of 3.5-foot [FL] one cannot distinguish them, one needs to employ a good instrument. This cluster contains no nebulosity.

Then again, Messier himself thought this cluster was only two arc-minutes in diameter, when it reality it turns out to be fifteen.

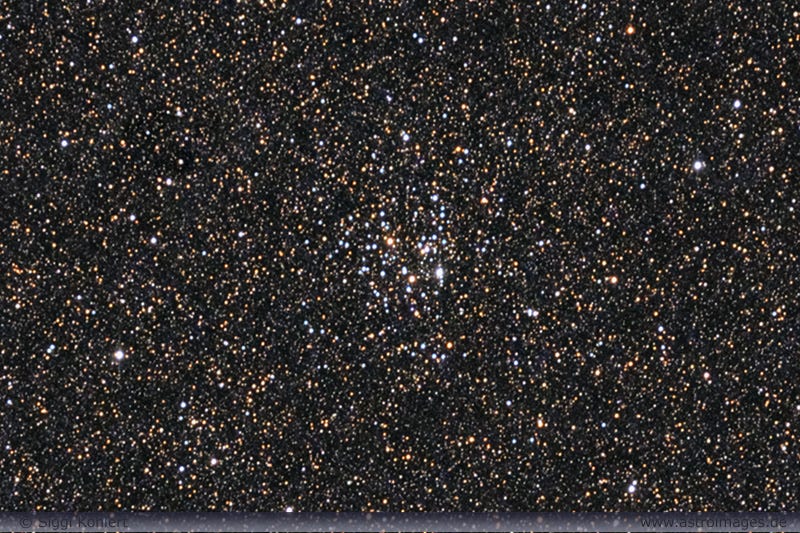

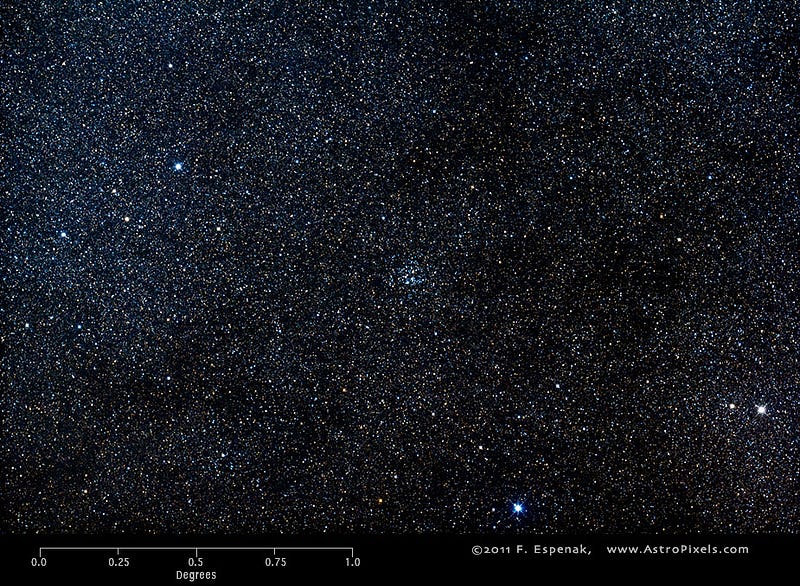

While the image above might be only slightly better than what Messier would’ve seen, let’s take a look at what a modest, modern observer might see with today’s equipment.

There are clearly plenty of stars in this cluster, but also a bizarre “dark spot” towards the center. While we see nebulosity — evidence of light-blocking dust and reflective, nebulous gas — in younger star clusters, particularly from ones in-or-near regions that are still forming stars, it normally takes only ten million to a few tens-of-millions of years for all that neutral gas to be ionized and blown back into not only interstellar, but inter-cluster space.

So what’s the deal here?

When we look at the stars of Messier 26, we find quite compellingly that the stars are much older than that: they give us an age of 89 million years, or slightly older than the Pleiades. With even a few B-stars left, of class B8 and B9, it can’t be all that old, but also wouldn’t be any younger than that without having brighter, hotter main sequence stars present, too. Practically all the other star clusters that we know of that are that age — or even considerably younger — have no light-blocking dust left in them.

And yet, light-blocking material is very clearly what we’re looking at here, as a glimpse in the infrared (at 2-micron wavelengths) shows.

What might be happening, then, is not that there’s dust in the cluster itself, but rather in interstellar space between us and this cluster. After all, it is 5,000 light-years away, and situated along the galactic plane. It’s possible, then, that there would be some intervening matter along the line-of-sight.

If we take a look at a wide-field view, it turns out that’s exactly what we see.

So it isn’t that there’s anything wrong with this cluster, or that its stellar density drops towards the core, or that it’s held onto its light-blocking dust far longer than a cluster of its size and age ought to. Rather, it just happens to be in an unusual location — caught partially behind a galactic dust lane — that gives it its unique appearance!

There are plenty of red giants present in here, just as you’d expect, evidence that the once-hotter, more massive stars are coming to the end of their lives. Over the next few million years, these stars — the prominent, red ones you see — are expected to blow off their outer layers into planetary nebulae, the fate of all such stars that are red giants today without enough mass to go supernova.

And while there aren’t any spectacular professional images of Messier 26 — sorry, everyone; it’s never been viewed by Hubble — there are some amateur ones that, at the very least, would’ve blown Messier himself away. Including this masterpiece of the cluster’s brightest, most core members.

250 years ago, this cluster was discovered, and despite the fact that only a few others like it were known at the time, it was a great disappointment. Today, we know of thousands such clusters, and this one has turned out to be exciting and unique, shedding light on not just the stars inside of it, but on how remarkably complex the space between a cluster and ourselves can be!

And with that, we come to the end of one of our final Messier Mondays. With just three objects to go now, take a look back at all your favorites:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M16, The Eagle Nebula: October 20, 2014

- M17, The Omega Nebula: October 13, 2014

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M19, The Flattened Fake-out Globular: August 25, 2014

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M22, The Brightest Messier Globular: October 6, 2014

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M26, The Could-Be-Better Cluster: November 3, 2014

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M28, The Teapot-Dome Cluster: September 8, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M54, The First Extragalactic Globular: September 22, 2014

- M55, The Most Elusive Globular Cluster: September 29, 2014

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M69, A Titan in a Teapot: September 1, 2014

- M70, A Miniature Marvel: September 15, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

- M110, Messier’s Final Galaxy: October 27, 2014

And come back next week, as we look to the skies once again for another deep-sky wonder, here on Messier Monday!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!